По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

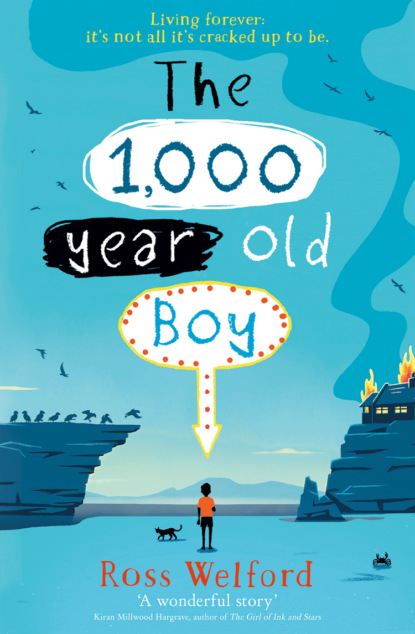

The 1,000-year-old Boy

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

(#u2dc64084-8d5f-5437-b932-9f3ddf1bbed9)

South Shields, AD 1014

We sat on the low cliff, Mam and I, overlooking the river mouth, and watched the smoke from our village over on the other side pluming into the sky and mixing with the clouds.

Everyone calls the river the Tyne. Back then, we pronounced it ‘Teen’, but it was just our word for river.

As we sat, and Mam wept and cursed with fury, we heard screams from across the water. The smell of smoke from the burning wooden fort on the clifftop drifted towards us. People – our neighbours mostly – huddled on the opposite bank, but Dag the ferryman was not going to go back for them. Not now: he would be killed too. He had run away from us, stammering apologies, as soon as his raft had touched the shore.

Above the people cowering on the bank, the men who had come in boats appeared. They paused – arrogantly, fearlessly – then walked over to their prey, swords and axes at the ready. I saw some people entering the water to try to escape. They would not get far: a smaller boat waited mid-river to intercept them.

I lowered my head and buried it in Mam’s shawl, but she pulled it away and wiped her eyes. Her voice trembled with rage.

‘Sey, Alve. Sey!’ That is how we spoke then. ‘Old Norse’ it is called now, or a dialect of it. We didn’t call it anything. She meant, ‘Look! Look at what they are doing to us, those men who have come from the north in their boats.’

But I could not. Getting up, I walked in a kind of daze for some distance, but I could still hear the murder, still smell the smoke. I felt wretched for being alive. Behind me, Mam pulled the little wooden cart that was loaded with whatever stuff we’d managed to fit onto Dag’s, river ferry.

My cat Biffa walked beside us, darting into the grass on the side of the path in pursuit of a mouse or a grasshopper. Normally this made me smile, but I felt as empty as if I had been cut open.

A mile or two on, Mam and I found a cave in a deep, sheltered bay. The sun was strong enough to use the old fire-glass that had belonged to Da: a curved, polished crystal that focused the sunlight into a thin beam that would start a fire. I was scared the raiders would come after us, but Mam said they would not, and she was right. We had escaped.

Three days later, we saw their boats heading out to sea again and I made the biggest mistake of my life. A mistake that I waited a thousand years to put right.

(#u2dc64084-8d5f-5437-b932-9f3ddf1bbed9)

If you want to ask me, ‘Why did you do it?’, go ahead: I do not mind. I have asked myself that many, many times. I still do not know the whole answer.

All I can say is that I was young, and very, very scared. I wanted to do something – anything – that would make me feel stronger, better able to help Mam, better able to protect us both.

And so I became a Neverdead, like Mam.

It began long ago, and when I say long ago I mean ages, literally. This is what happened.

My father had owned five of the small glass balls that were called livperler.

Life-pearls.

They were the most valuable things we possessed. Mam said that they might be the most valuable things in the world, ever.

People had killed to obtain them; Da had died trying to keep them. And so we told no one that we had them.

Now there were three left. One for Mam, and two for me when I was older.

I knew all that. Mam had told me enough times. ‘Not until you are grown, Alve. You must be patient.’

But I could not wait.

On the third evening in the cave, while Mam was out looking for fresh water, I opened the little clay pot and took out the livperler. Although they were old, the glass marbles shone in the half-twilight from outside, the thick liquid within seeming to glow amber when I held one near the fire.

Biffa sat up on a little rocky shelf on the opposite side of the fire, her yellow eyes shining like the glass balls. Did she know? She mewled: the little cat-growl that made us think she was talking to us. Biffa often seemed to know things.

Crouching on my hunkers, I took the knife, the little steel one that had belonged to Da, with the blade that hinged into the wooden handle, and held it to the flame. I glanced at the mouth of the cave to check I was alone, and swallowed hard.

When I drew the hot blade twice across my upper arm, the blood seeped out. Two short slashes, like the scars Mam had. Like Da had had. I do not know if doing it twice made any difference; probably not. It was just the way.

It did not hurt until I used my thumbs to pull the wounds apart. I bit down on the life-pearl and the glass cracked. The yellowish syrup oozed out like the blood from my cuts. I gathered it on my fingertips and rubbed it into the wounds. Then I did it again, and again, until there was none left. It stung, like a fresh nettle in the spring.

What happened next was an accident. I have played it over and over in my mind, like people play ‘videotapes’ today. Could I have done anything differently?

I do not know.

I think Biffa was just curious. She cannot have known – but, as I said, she was a very knowing cat. Suddenly she gave another little growl and leapt at me, right across the low flames of the fire. The knife was still in my hand and, without thinking, I raised it: a defensive reflex. It nicked her front paw slightly, but she did not mewl again. When she landed, I spun round and, in that action, my tunic dislodged another life-pearl from the low rock shelf where I had placed them. I was unbalanced, and my bare foot came down on it, hard, and it cracked open.

I stared at it, horrified, for a few seconds.

It was bad enough that I had disobeyed Mam’s orders. But I had now wasted another precious life-pearl.

The thick amber liquid began to drip out of the rock. Thinking only that it should not be wasted, I grasped Biffa by the long skin of her neck and rubbed the liquid into her cut paw.

(It was not mischief, as I said to Mam again and again over the years. I was just trying not to waste it.)

Then I wrapped up my arm with a long strip of clean cloth, and tied another round Biffa’s leg. She did not even seem to mind. She licked her whiskers, yawned and curled up again. I could see Mam’s shape against the blue twilight sky as she came back to the cave with a bucket of water, and I was overwhelmed with shame.

I sometimes think I still am.

By then, I had seen eleven winters.

I was to stay eleven years old for more than a thousand years.

(#u2dc64084-8d5f-5437-b932-9f3ddf1bbed9)

All of that happened ages ago.

I have tried telling my story before, but I soon learnt that people do not want to know. I have to leave out crucial details like the life-pearls, and so people think I am teasing them (at best) or that I am dangerously mad (at worst).

So I stay schtum, as you say.

I sometimes wonder if people’s reactions would be different if I looked old? That is, if I were wrinkled and stooped and bald, with a quavery voice, and huge, veiny ears and badly fitting clothes. Then again, people would not bother with the ‘teasing’ bit, would they? They would immediately assume that age had sent me mad.

‘Bless ’im, old Alf,’they would say.‘He was on about the Vikings again today.’

‘Was ’e? Aww. It was Charles Dickens yesterday. Reckoned he’d met him!’

‘Really? Poor old soul. Mind, he’s harmless, in’t he? Away with the mixer, like, but harmless.’

As it is, I do not look old at all: I look about eleven.

At the point I stopped ageing, the Vikings had more or less completed their occupation of north-eastern England. It was the Scots that Mam and I were fleeing. It was to be another fifty or more years before the south of the country was invaded: 1066, by the Normans (who were basically Vikings who had learnt French, if you ask me, but nobody does. Nor-man, north-man – you can see the link).