По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

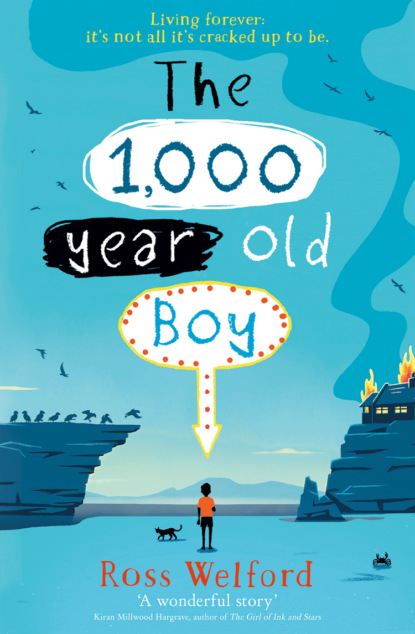

The 1,000-year-old Boy

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

You probably do not remember 1934. Me, I liked it. We had no refrigerator or telephone, but nor did most people. Televisions and computers had hardly even been invented and it would be another sixty or more years before everyone used email and the internet, and everybody knew everything about everybody else. Which was not entirely a good thing if you were trying to hide a secret.

By then, Mam and I had been living in Oak House for nearly eighty years. Mam had bought it in 1856 for £300 cash. You could do that then. It was all legal, and Mam and I had enough money.

It was certainly remote, and perfect for us. There were no housing estates nearby then. We grew stuff on a little patch of ground that had been cleared when the cottage was built. We had a goat called Amy and some chickens. (We did not give names to the chickens, because we sometimes ate them.)

Biffa loved it. The house had been empty for a while when we moved in, and there were a lot of mice. Biffa caught them all within a few weeks.

We read a lot, and – once it had been invented – we listened to the radio, which we called the wireless.

Once or twice a week, Mam would cycle into Whitley Bay on our rickety old bicycle, and sometimes I would go instead to fetch groceries. I made sure I went outside of school hours so that no one would think I was playing the wag.

There was a grocery shop in Eastbourne Gardens run by a couple, Mr and Mrs McGonagal. He was tall and thin with huge red ears and sharp eyes, and she was short and dumpy. They had a boy my age called Jack who helped behind the counter.

Jack and I eventually got to the point where we would say ‘hello’ and he once helped me put the chain back on my bike. I let him have a ride on it to pay him back and he said, ‘Where do you live?’

‘Hexham,’ I lied. I knew the routine. ‘I’m just visiting my aunt.’

That was the story that worked, if anyone asked – which they seldom did because we did not talk to many people. Hexham is a town about forty miles away: near enough not to be unusual, but far enough not to be familiar.

‘Where do you go to school, then?’ asked Jack. This was on a school-day afternoon, at about 4pm.

‘In Hexham,’ I said. ‘Only our schools are closed this week. It’s a local holiday.’

‘Cor,’ said Jack. ‘Jammy!’

And that was it: no further questions. I liked Jack. I gave him a backer on my bike down to the Links and we threw stones at a tin can. He could walk on his hands, and when he tried to teach me we laughed and laughed. It was fun.

It was quite a long time since I’d had a friend, and Jack seemed a bit lonely too. So, when it began to get dark and I would have had to cycle home with no lights (and risk being stopped by a policeman who would take me home and ask awkward questions), I said to Jack, ‘I am coming back here on Saturday: shall we meet?’

And so we did. There was a brass band playing on the bandstand, and we ate chips (which I bought), looking at the big white dome of the Spanish City pleasure gardens and Jack told me about his dad who had once shot a moose in Canada, and …

Why am I telling you this?

Because you have to understand how hurt I was when my new friend Jack – funny, skinny Jack with his knobbly knees and his baggy shorts – betrayed me, although it was not even his fault. Well, not entirely.

(#ulink_5976fb6b-8dd1-5226-a6d2-32c8db79358e)

You see Jack grew older and I did not. It was always the way with friends, and it was always hard. I never got used to it.

After a year or two of knowing him, Jack started to wear long trousers. A year or two after that, he grew a wispy moustache, and his voice became deeper.

So far as he knew, I came to visit my ‘aunt’ most weekends. I had several periods when I said I was recovering from a mystery illness, which required longer stays to benefit from the sea air, and there were always the summer holidays.

Jack would even come to our house in the woods. Mam liked him but she was wary. She was not keen on anybody getting too close.

‘It will end badly, Alve,’ she would warn. I did not want to believe her. Jack would be different, I was sure of it.

If Jack thought it odd that I did not grow taller, or grow hair on my legs, he said nothing. Not so his mother, though.

‘Ee, Alfie Monk, your mother not feedin’ you or summin’?’ Mrs McGonagal said to me one day in the shop. ‘Look at ye! There’s more growth on a mouldy cheese.’

‘Ma!’ said Jack, but he was laughing too. I don’t think he intended to be mean, but, when he laughed, I shrivelled inside because I’d seen it all before. The suspicion, the mistrust, the gradual – or sometimes sudden – withdrawal of friendship from the strange boy who does not get older.

Not long after, I heard them talking about me. I had come into the shop; the tinkling bell that normally announced a customer’s arrival was broken, so nobody knew I was there.

I heard Jack in the back room of the shop. He was repeating his mother’s joke from before in his new, deeper voice.

‘… more growth on a mouldy cheese, I tell you!’

‘Come on, Jack. Don’t mock the afflicted. He’s prob’ly got some growth condition or summin’.’ The voice was a young woman: Jean Palmer, whom Jack had started courting. I had met her once or twice. She was pretty.

‘Alfie’s different. It’s not right,’ said Jack. ‘He’s not changed in five years. Five years! And have you heard how he talks? Reckons he’s from Hexham. Well, I know Hexham, and they don’t talk like that out there.’

By now, I had moved from my position by the counter and was sort of crouched down behind a stack of cardboard boxes. I did not want them to come out and see that I had been listening.

‘Aye, he does talk funny, I’ll give y’that,’ Jean Palmer said. ‘But I like him.’

‘He’s not right, Jean. And his aunty’s not right, either. Never looks you in the eye when she’s talking to you. Living out in the woods like that – with a goat of all things. Old Lizzie Richardson told Ma she used to know her years ago, in North Shields, when she had a son of her own, and he was called Alfie as well. That’s odd, isn’t it?’

‘Lizzie Richardson? She’s over eighty.’

‘That’s what I’m saying, Jean. And, if Mrs Richardson knew her back in Shields, that puts that Mrs Monk at sixty-odd if she’s a day.’

‘Well, she’s lookin’ good on it is all I can say.’

At that point, another customer came in and shouted, ‘Hello?’ and hardly noticed as I scuttled out. I cycled home, despondent.

This was how it happened, again and again, although this time was quicker than I was used to.

You see, it is simply not possible to get no older and expect nobody to notice. People talk; people gossip. You can often get away with it for much longer than you might expect, but eventually people behave just like, well … people.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: