По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

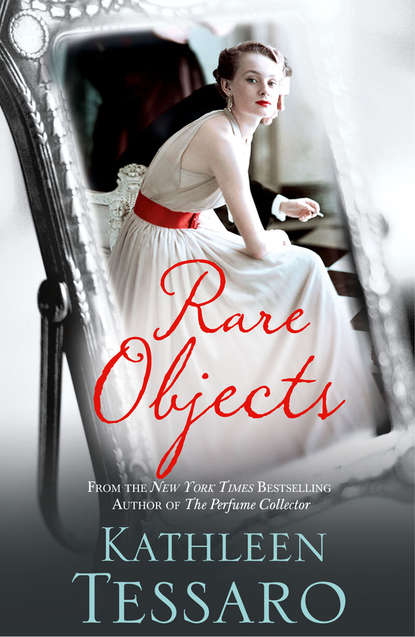

Rare Objects

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“It just doesn’t make sense. You’ve been his private secretary for almost a year, and then, out of the blue, you’re suddenly out of work and back in Boston!”

“Well, at least I’m home. Aren’t you glad about that?”

She gave a halfhearted shrug. “I’d rather have you make something of yourself. You were on your way in New York. Now you’ll have to start all over again.” Scooping some porridge into a bowl, she set it down in front of me. “I’ll hang the gray suit in your room.”

I gnawed at my thumbnail. I didn’t want porridge or the suit. The only thing I wanted now was to crawl back into bed and disappear.

She gave my hand a smack. “What are you doing? You’ll ruin your nails! Don’t worry so much. With your training and experience, you’re practically a shoo-in.”

I prodded the porridge with my spoon.

My experience.

If only my experience in New York was what she thought it was.

SOMEWHERE IN BROOKLYN, NOVEMBER 1931 (#ulink_a57c50a3-9930-5cdb-b469-36ac3760bdf3)

I was falling, too fast, with nothing to stop me … down, down, gathering speed …

I came to with a jolt. I was sitting on the side of a bed wearing only my slip and stockings—a wrought-iron bed in a cold, dark bedroom. Only it wasn’t my bed or my room.

Suddenly the floor veered beneath me, the walls spinning, faded yellow flowers on the wallpaper melting together. Please, God, don’t let me be sick! I pressed my eyes closed and held on to the bed frame tight.

I had to think. Where was I, and how exactly had I gotten here?

It had been a long, dull night at the Orpheum dance palace on Broadway where I worked. The joint was full of nothing but out-of-towners and hayseeds—guys with little money and lots of expectations. By the time we’d closed and I’d cashed in my ticket stubs, I was ready for some fun. Another girl, Lois, had made a “date” with a customer, and he had a friend … Was I game?

Why not? After all, it wasn’t like I had anything to lose.

I remembered two big men, grinning like excited schoolboys, in New York for a convention and laughing the way tourists do—too easily and too hard, willing themselves to have the best night of their lives. One was reasonable-looking, and the other—well, let’s just say no one was going to mistake him for Errol Flynn or Douglas Fairbanks. But there’s that old adage about beggars and choosers, and tonight I felt like a beggar for sure. The last thing I wanted was to be alone and sober at the same time. So we all piled into a cab. Hip flasks were passed round; I remembered Lois sitting on someone’s lap, singing “Diggity Diggity Do.”

We drove to Harlem, to a place called Hot Feet. There was a band from New Orleans and a chorus line of smooth-skinned Negro girls dressed up with grass skirts and bone necklaces, shaking and shimmying for all they were worth. The moonshine had kicked in by then, and I was feeling a bit less rough round the edges. Lois was sure she saw Oweny Madden and the boxer Primo Carnera at the next table, and one of the guys, the ugly one, forked out for a bottle of real gin.

God, my mouth was as dry as the Sahara! What time was it now? What had happened to Lois?

I tried to stand. My head pounded, my stomach swooned. Easy does it. Not too fast.

Someone shifted in the bed next to me.

Shit. Please don’t let it be the ugly one.

I tried not to look. A face you never saw was a face you never remembered. I’d learned that much in New York.

I eased myself up. My knees were sore, and there were holes in my stockings. I guess I must’ve fallen. Going over to the window, I pushed aside the curtain. The street was residential, narrow row houses with uneven terraces crammed together, lamps glowing eerily over abandoned lots between. I searched for something familiar on the skyline, a bridge or a building, but couldn’t see anything. One thing was certain: I was definitely on the wrong side of the river.

I seemed to remember talk of going to a hotel to carry on the party—someplace like the Waldorf or the Warwick. So why was I stranded in some cheap boarding house in Queens or Yonkers with no idea where I was or how I was going to get home?

The man rolled over on to his side and began to snore. I had to get out of here, before he woke.

Where were my clothes?

I nearly stumbled over something and picked it up. But this dress wasn’t mine.

Then a memory came of the day before. I’d borrowed a dress from Nancy Rae, the girl down the hall at the Nightingale boarding house, where I rented a room. It was Nancy’s good-luck dress, a hunter-green serge she’d been wearing when she landed her job at Gimbles; all the girls wanted to borrow it for interviews. I’d given her a dollar for the privilege and even gotten up early to steam the box pleats of the skirt through a towel to make them crisp and sharp without going shiny. When I finished, they fluttered open like a fan round my legs.

See that’s the thing about luck—it has to be courted. You have to seduce it; reel it in slowly without arousing suspicion. It’s so precious that every tiny thing matters—what you wear, which side of the road you walk on, the tune you whistle, or how many birds you see out the window. Nancy Rae’s hunter-green dress had stood in fate’s presence and felt its light touch. And when fate favors anything, you’d best pay attention.

I’d been working as a taxi dancer at the Orpheum for months, waltzing with strangers night after night for a dime a dance. But when I saw the advertisement in the back of the Herald for “a young woman of exceptional executive secretarial skills,” I knew that my luck was about to change.

So I gave Nancy the dollar, ironed the dress, and set out first thing in the morning with my notebook and résumé in hand.

But when I arrived at the address, a full hour ahead of time, there were already fifty girls ahead of me, lined up around the corner of the office building, all clutching notebooks and reference letters, all looking hungry and determined and ferociously confident. I lasted three hours waiting in the cold before the girl ahead of me, a short brunette with a frizzy permanent wave and a big run in her stocking, turned round and announced, “You know they’re not going to see all of us, don’t you? I’ve been standing in lines for months, just trying to get my foot in the door. I tell you, we’re waiting here for nothing, like a bunch of saps!”

No one answered her. You can be six inches from someone’s face in New York City and they can still stare straight through you, like you’re not even there. But when I looked around, I could see from the other girls’ faces that what she said was true.

Then she leaned in closer. “I know a guy who runs the door on a joint off Lexington. If you sit at the bar and are friendly to the customers, they don’t mind serving you for free, especially if you’re good-looking.”

I didn’t know why she was telling me. Did I look like the kind of girl who was at home on a barstool? I lifted my chin a little so I was looking down at her and sneered, “What of it?”

She wasn’t put off. “Besides”—she jerked her head at the others, shivering ahead of us—“today’s not our day, sister.”

There were an awful lot of us. The line stretched right up the block and disappeared round the corner. And it would be so nice to sit down and get warm. I didn’t have any money for breakfast that morning, so my stomach was playing a selection of squeaky, off-key tunes all on its own.

Still, if they could only see my qualifications, give me a chance.

The poodle-haired brunette wasn’t waiting any longer. “Fine!” She rolled her eyes, the voice of reason in a world full of idiots. “I was trying to do you a favor, but if you want to catch frostbite just to be told thanks but no thanks, that’s up to you!”

“Is it heated?” I’m on the thin side, being warm is something of an Achilles heel for me.

She shot me a look like I was from the backwoods of West Virginia. “Sure it’s heated! And they got free peanuts at every table, as much as you can eat.”

As soon as I stepped out of line, the girl behind me shoved forward like I was all that was standing between her and destiny. I tossed a sad smile her way just to show her I knew better. I was off to be fed and watered for free. I’d graduated from waiting around.

The poodle brunette had a name like Ivy or Ida or Elsa, and once inside the club on Lexington, she told me right where to sit and how to play it. She got us both a basket of peanuts and we ate as much as we could stand before she brushed the shells off the table and swung into action. Hers was an entirely democratic brand of lazy hospitality—everyone was included in its warm glow, but no one was singled out; every guy figured he had a chance. Maybe because of this she was a past master at getting men to buy more rounds. It wasn’t long before the morning slipped into the afternoon and the afternoon into the evening. I probably ate a pound of peanuts that day. Soon it was time to head over to Broadway to begin another shift at the dance palace.

Now here I was, eighteen hours later, tripping over Nancy Rae’s lucky green dress, crumpled in a heap on a stranger’s floor.

My life was full of cracks, ever-widening gaps between the person I wanted to be and the person I was. When I first came to this city, they used to be small enough to laugh off or ignore. But over the past year they’d grown wider, deeper. I’d fallen in one again last night.

This was the last time, I promised myself.

The very last time.

I found my coat in the corner, thrown over a chair. My new hat, the one I’d splurged on when I got my first job, had been stepped on, squashed into a flat felt circle, the black net that had framed my face so charmingly torn and dangling miserably from a few threads.

I got dressed. Unfortunately I’m good at this—navigating creaky floorboards and sleeping men, finding clothes in the dark. It’s a loathsome talent.

All I needed now was my handbag.