По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

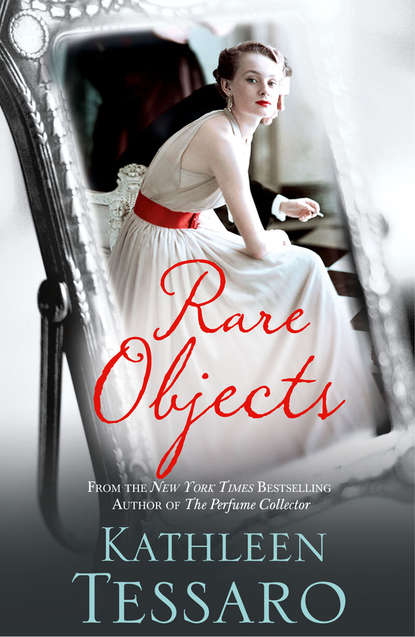

Rare Objects

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I stared out the window, pressing my palms tightly against the coffee cup for warmth. Sitting here in the kitchen just before the day truly began, looking out into the darkness, calmed my nerves. The city was shadowy, lit only by streetlamps. But still the North End was already awake and opening for business.

The fruit seller across the street, Mr. Contadino, was setting up his stall, squinting as he cranked open his green-striped awning in the icy wind, the air swirling with snowflakes. He had on a flat cap and a heavy woolen vest under his clean apron, and a pair of knitted fingerless gloves protected his stubby hands. Soon he would light the chestnut stove—a large iron barrel near the shop doorway with a coal fire in the base and fresh chestnuts roasting in the top. He sold them tender and hot in little brown paper bags for a penny. Contadino’s chestnuts were a glowing beacon of civilization in the North End. The smell of the buttery flesh roasting and the delicious combination of cold air and the crackling fragrant heat radiating from the belly of the stove made it all but impossible not to stop as you passed by. Men collected there, speaking in Italian, smoking, laughing, warming their hands. In the morning they held tiny steaming cups of espresso, and in the evening cigar smoke, sweet and luxuriant, billowed around them in clouds.

As Ma was fond of pointing out, Contadino knew what he was doing. That chestnut stove brought him twice as much trade as any other fruit seller in the neighborhood had. “See, the Italians are smart. And they don’t drink. We made the right choice; we’re better off here.”

Here was the North End of Boston. Waves of immigrants had made the North End their home over the years. It had been a Jewish ghetto before the Irish took over, but most had since moved south; it was firmly Italian now. We had second cousins living in the South End, but Ma always considered herself a North Ender, valuing privacy over familiarity. “We don’t have to live in everyone’s back pocket,” she used to say.

“A suit looks more professional.” Ma hated to lose an argument. “Just because you’re not working doesn’t mean you can’t look respectable.”

Respectable was one of Ma’s favorite words, along with ladylike and tasteful. Quaint, old-fashioned words. To me they sounded as relevant as bustle and parasol; faded echoes from another era when good looks, pleasing manners, and modesty were all that were required in the female arsenal. Nowadays, they just made you seem backward.

“I’ll think about the suit,” I told her, watching as Mrs. Contadino, wrapped in a shawl, came out into the cold with her husband’s coat. He waved her away, but she won in the end; he had to put it on before she would go back inside.

Then I remembered what day it was.

“It’s the eighth today, isn’t it?”

I saw her smile. Maybe it pleased her that she didn’t have to remind me. “That’s right. It’s a sign. Mark my words: it’ll bring you luck!”

Underneath Ma’s worldly exterior a superstitious child of Ireland still lingered, clinging to all the impossible magic of the supernatural.

“Do you think?” I swallowed some more coffee.

“Absolutely! You were born at night, Maeve. That means you have a connection to the world of the dead. If you ask for their help, they’re sure to come.” She topped up my cup. “I’ll be going to mass later if you want to join me. I’m sure he’d like it if you came too.”

It had been a long time since I’d been to mass. Too long.

I looked out at the pale gray dawn, bleeding red-orange into the sky. “Go on, Ma, tell me about him,” I said, changing the subject. It was also a tradition, something we did every year on the anniversary of my father’s death. And who knew, maybe today it would make a difference; maybe against all reason, my dead father would lure good fortune to me.

“Oh, Maeve!” She shook her head indulgently. “You know everything there is to tell!”

Every year she protested—not too hard.

“Go on!”

And every year, I insisted, for old times’ sake.

She paused, teasing the moment out like an actress about to play a big speech. “He was a remarkable man,” she began. “A graduate of Trinity College in Dublin. A true gentleman and an intellectual. Do you know what I mean when I say that?” She took a long drag. “I mean he had a hunger for knowledge; a deep longing for it, the way that some people yearn for food or wealth.” She smiled softly, exhaling, and her voice took on a tender, dreamy tone. “It made him glow; like he was on fire from the inside out. His eyes used to burn brighter, his whole being changed when he was speaking on something that interested him, like literature or philosophy. He was good-looking, yes,” she allowed, “but if you only could’ve heard him talk … Oh, Maeve! His voice was a country—a rich green land populated with mountains and rivers …”

She had the gift, as the Irish would say, an ear for language. Her talents were wasted as a seamstress.

“He drew you into other places. Other worlds. He made the obscure real and the unfathomable possible. He would’ve been a great man had he lived. There was no doubt. His brain was like a whip.” She flicked a bit of ash into the sink, pointed her cigarette at me. “You have that. You have a sharp mind.” Her words were an accusation rather than a compliment. “And his eyes. You have his eyes.”

There was just one photograph of Michael Fanning. It sat on the mantelpiece in the front room, a rather startling portrait of a handsome young man staring directly into the camera. His broad, intelligent forehead was framed by waves of dark locks, and his features were fine and even. But it was the fearless intensity of his gaze and the luminous pinpoints of light reflected in his black pupils that drew you in. It was impossible not to imagine that he was looking straight at you, perhaps even leaning in closer, as if he’d just asked a question and was particularly interested to hear your answer. It was an honest face, without artifice or pretension, and as far as I was concerned, the most beautiful face in the world.

I’d never known him. Ma was a widow and had been all my life. But his absence was the defining force in our lives, a vacuum of loss that held us fast to our ambitions and to each other. He’d always been Michael Fanning, never father or Da. And he wasn’t just a man but an era; the golden age in Ma’s life, illuminated by optimism and possibility, gone before I was born. I’d grown up praying to him, begging for his guidance and mercy, imagining him always there, watching over me with those inquisitive, unblinking eyes. God the Father, the Son, the Holy Ghost, and Michael Fanning. In my mind, the four of them sat around heaven, drinking tea, smoking cigarettes, taking turns choosing the forecast for the day.

“What time are you going to mass?”

“Six o’clock. I want to go to confession before.”

Confession.

Now there was the rub. I certainly wasn’t going to confession.

“Well,” I said vaguely, “I’ll see what I can do, Ma.”

My parents met in Bray, a small seaside town in county Wicklow, Ireland. Fresh from university, Michael Fanning turned his back on his family’s considerable resources to teach at the local comprehensive, where Ma was a student in her final year. After a brief and clandestine courtship they married, against both their parents’ wishes, when she was just seventeen. They planned to immigrate to New York, where Michael’s cousin was already established. But he contracted influenza, and within three days was dead. No one from either family came to the funeral.

With what little money remained after burial costs, seventeen-year-old Nora set sail for America rather than turn to her family for help. The only ticket she could afford landed her in Boston, and so I was born six months later, in a tiny one-room apartment above a butcher’s shop in the North End, with no heat, hot water, or bathroom. I was delivered by the butcher’s wife, Mrs. Marcosa, who didn’t speak English and had seven children of her own, most of them kneeling round the bed praying as their mother, sleeves rolled high on her thick arms, shouted at my terrified mother in Italian. When I finally appeared, they all danced, applauded, and cheered.

“It was one of the most wonderful and yet humiliating days of my life,” Ma used to say. “The Marcosa children all loved to hold you because of your red hair. They found it fascinating. The whole neighborhood did. I couldn’t go half a block without someone stopping me.”

She took in seamstress work during the day, piecing together cotton blouses for Levin’s garment factory nearby, and in the evenings she traveled across town to clean offices, taking me with her in a wicker laundry basket, wrapped in blankets. Setting me on the desks, she made her way through the offices, dusting, polishing, and scrubbing, singing in her low soft voice from eight until midnight before heading back across the sleeping city.

But she always hungered for more. And even when she joined the alterations department at Stearns, she’d already had her sights set on moving from the workroom to the sales floor. She enrolled in Sunday-afternoon speech classes from an impoverished spinster in Beacon Hill, taking me with her so that I could learn to enunciate without the telltale lilt of her brogue or, worse, the flat vowels of the Boston streets. I suppose that’s something we have in common—the unshakable conviction we’re destined for better things.

Year after year she continued to apply for a sales position, ignoring the rejections and snubs, refusing to try elsewhere. “It’s the finest department store in the city,” she maintained. “I’d rather mop floors there than anywhere else.” She could endure anything but failure.

Stubbornness is another trait we share.

She still wore the plain, slim gold band her husband had given her on her wedding ring finger, not just as a reminder but also as a safeguard against unwanted male attention.

“Your father would’ve been proud of you, Maeve, getting your secretarial degree.” She took a final drag from her cigarette, stubbed the end out in the sink.

I looked down. “Oh, I don’t know about that.”

“Well, I do.”

All my life, she’d been a medium between this world and the next, advising on what my father would’ve wanted, believed in, admired.

“He had everything it took to really be someone in this world—intelligence, breeding, a good education. Everything, that is, except luck. I just hope yours is better than his.” She sighed.

“What do you mean?”

“Nothing. You’re a clever girl. A capable girl.” Leaning in, she scrubbed the coffee stains out of the sink. “It’s just a shame you lost that job in New York.”

A knot of guilt and apprehension tightened in my stomach. This was the last thing I wanted to talk about. “Let’s not go into that.”

But Ma was never one to let a subject die an easy death if she could kick it around the room a few more times.

“It just doesn’t make sense,” she went on, ignoring me. “Why did Mr. Halliday let you go after all that time?”

“I told you, he’s traveling.”

“Yes, but why didn’t he just take you with him, like he did before? Remember that? You gave me the fright of my life! I didn’t get a letter from you for almost six weeks!”

It was if she knew the truth and was torturing me, the way a cat swats around a half-dead mouse. I glared at her. “Jeez, Ma! How would I know?”