По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

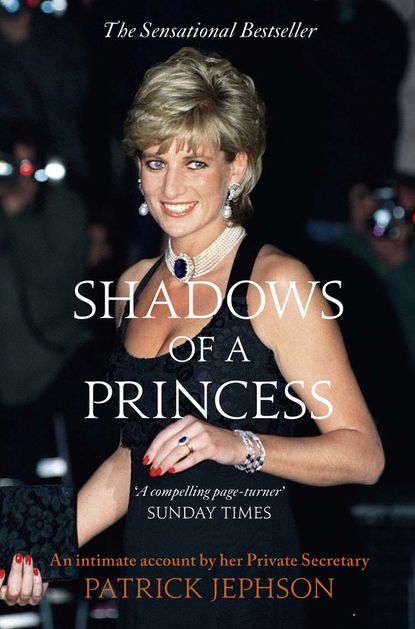

Shadows of a Princess

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The underlings, therefore, had to look after themselves. It did not take me long to realize that, whenever I was uncertain what to do next in any royal situation, usually the best option was to do nothing and enjoy whatever pleasurable compensations were to hand. A sense of humour was essential survival equipment in the palace jungle (but nothing too clever). So was an ability to enjoy food and drink.

To these I secretly added an ability to enjoy plane-spotting. It turned out to be quite useful. Many of my tensest moments were experienced in royal aeroplanes, but surprisingly often I could deflect the Princess’s fiercest rocket with a calculated display of nerdish interest in what I could see out of the window.

As it happened, I was able to indulge this lonely vice almost immediately as I caught the bus back to Heathrow. Farewells at KP were polite but perfunctory and Richard and Anne gave no hint as to the outcome of my interview. Richard ventured the comment that I had given ‘a remarkable performance’, but this only added to the general air of theatrical unreality. I was pretty sure I had eaten my first and last royal Jersey Royal.

Back in Scotland, my despondency deepened as I inhaled the pungent aroma of my allocated bedroom in the Faslane transit mess. It was not fair, I moaned to myself, to expose someone as sensitive as me to lunch with the most beautiful woman in the world and then consign him to dinner with the duty engineer at the Clyde Submarine Base. And how could I ever face the future when every time the Princess appeared in the papers I would say to myself – or, far worse, to anyone in earshot – ‘Oh yes, I’ve met her. Had lunch with her in fact. Absolutely charming. Laughed at all my jokes …’

Now thoroughly depressed, I was preparing for a miserable night’s sleep when I was interrupted by the wardroom night porter. He wore a belligerent expression so convincing that it was clearly the result of long practice. No doubt drawing on years of observing submarine officers at play, he clearly suspected he was being made the victim of a distinctly unamusing practical joke. In asthmatic Glaswegian he accused me of being wanted on the phone ‘frae Bucknum Paluss’.

I rushed to the phone booth, suddenly wide awake. The Palace operator connected me to Anne Beckwith-Smith. ‘There you are!’ she said in her special lady-in-waiting voice. ‘We’ve been looking for you everywhere. Would you like the job?’

TWO (#ulink_b8b83f24-9b52-5d43-a580-e686cccde169)

IN THE PINK (#ulink_b8b83f24-9b52-5d43-a580-e686cccde169)

Some events can be seen as milestones only in retrospect, while at the time they pass almost unnoticed. This was not such an event. The court circular for 28 January 1988 spelt it out in black and white: Jephson was going to the Palace and an insistent inner voice told me his life would never be the same again.

Reaction among my friends and relations was mixed. The American, Doug, thought it was a quaint English fairy tale. My father thought it inevitably meant promotion (he was wrong). My stepmother thought it was nice (she was mostly right). My brother thought it would make me an unbearably smug nuisance (no change).

Although I would never have admitted it, I thought I must be pretty clever, and I apologize belatedly to everyone who had to witness it. That was lesson one: breathing royal air can seriously damage your ability to laugh at yourself. It is sometimes called ‘red carpet fever’ and usually only lasts a few months, but severe cases never recover and spend the rest of their lives believing in their own acquired importance.

I reported to the offices of the Prince and Princess at the end of April. In those halcyon days their staff occupied a joint office in St James’s Palace. The couple shared a private secretary, a comptroller, a press secretary and numerous administrative officials who helped run an organization some hundred strong. They themselves lived at KP and made the journey to ‘SJP’ when required.

In the Prince’s case this was frequently and – unlike his wife – he kept an office at St James’s for the purpose. Given the clutter of books and papers with which he usually surrounds himself, this elegant room – all limewash panelling and thick carpet – seemed strangely anonymous, its few personal touches almost an afterthought. The cleverly concealed lighting and carefully selected antiques seemed to have taken priority. Its enormous desk was naked but for a photo of William and Harry, while from the mantelpiece an unusual triple-portrait photo of his mother, aunt and grandmother looked down on the inmate with matronly appraisal. The place smelt of polish and expensive fabrics and in every way satisfied what I suppose are masculine preferences in orderliness and understated good taste. It was a constant reminder – along with its equivalent in cars, clothes and other accoutrements – that the heir’s cares were shouldered in at least tolerable comfort.

The penalty of operating out of two palaces was the amount of time – and often anxiety – expended on getting from one to the other. My tendency to plan journeys to coincide with the sedate passage of the Household Cavalry always raised my blood pressure. I almost came to believe that the Mounted Division only ventured out in splendour to block Constitution Hill when they had word that the Princess had summoned me to an urgent meeting in KP.

There were benefits too. Even the most conscientious private secretary could sometimes be grateful that his boss kept at a distance from the office. Moreover, when peace and quiet and decent coffee were elusive at SJP, I often took refuge in the tranquillity of the KP Equerries’ Room. The house staff always kept a warm welcome and would let you raid the pantry. Also, more often than I cared to admit, it was useful to be ‘unobtainable’ while stuck in traffic somewhere on Kensington Gore, although the fitting of mobile phones to office cars made this an increasingly dodgy excuse.

The Wales household occupied offices in St James’s that had previously been used by the Lord Chamberlain’s Department. The previous occupants’ more sedate tastes were apparent in the dense brown carpet and heavy furniture. Against the sober backdrop of high ceilings, ornate plasterwork and yellowing net curtains the youthful Wales staff sometimes seemed like children who had set up their office camp in an abandoned gentlemen’s club. The average age could not have been more than 22, and the secretaries were almost without exception from backgrounds where girls were expected to be seen and heard and enjoyed being both.

At that time the office worked as one unit with Their Royal Highnesses’ private secretary – the genial Sir John Riddell – presiding over a team which, on the surface at least, owed equal loyalty to both. I soon discovered, however, that the Princess’s small component was still regarded as a minor addition to what was essentially an enlarged bachelor establishment. This was especially evident in the planning of joint programmes, when, as if part of the natural order, the Princess’s requirements took second place – and sometimes not even that, unless the Prince’s staff were gently reminded of her involvement. Despite this, thanks to a lot of goodwill, it was an addition that was loftily tolerated, despite its perceived irrelevance to the main work of the organization.

The private secretary’s room lay at one end of a string of smaller offices on the first floor of York House. At the other end a swing door separated us from the decidedly grown-up world of the Central Chancery of the Orders of Chivalry. Between the two I found offices for the deputy private secretary, the comptroller and the lady-in-waiting, interspersed with larger shared offices for lowlier forms of life such as equerries and secretaries.

My predecessor Commander Richard Aylard and his opposite number, the Prince’s equerry Major Christopher Lavender, shared an office that seemed to be the size of a small ballroom, inelegantly partitioned to make a small adjoining space for three secretaries (or ‘lady clerks’ in Palace-speak). I was planted behind a small table in a corner, from which I could observe the veterans at work. Now, I thought, I’ll find out what an equerry actually does.

Many people then – and since – made dismissive comments about equerries being needed only to hand round gin and tonic or carry flowers for the lady-in-waiting, both tasks being about on the limit of my perceived ability. I performed these tasks on numerous occasions, but even at the outset I knew there must be rather more to a job which provoked such envy and contempt. I had an idea – reinforced by a helpful introductory letter from Richard – that I was expected to help implement the Princess’s programme and generally act as a kind of glorified aide-de-camp.

Listening to the confident instructions being rapped out by Richard and Christopher in a series of seemingly incessant phone calls, I was gripped by panic. How would I ever know what to do? How would I ever develop the easy blend of nonchalant authority and patient good humour that seemed to be the better courtier’s stock in trade? Especially when all the time my novice high-wire act would be under unblinking scrutiny from royal employers, sceptical colleagues and – worst of all – the royal press pack.

My panic deepened as I contemplated my first task. Thinking he was easing me in gently, Richard had thoughtfully given me the job of writing a memorandum to the Princess outlining programme options for a forthcoming visit to the West Country. I stared transfixed at the notepad in front of me, my mind as blank as the paper. The letterhead grandly announced the writer as ‘Equerry to HRH the Princess of Wales’ and I dumbly wondered if I would ever have the temerity to sign anything that followed.

Eventually a lucky inspiration came to me. On the pretext of familiarizing myself with the office filing system (a feat still incomplete seven years later), I sauntered into the secretaries’ room. The girl-talk came to a temporary halt as three laughing pairs of eyes appraised me.

‘We’ve decided to call you PJ,’ the senior secretary said. ‘We can’t possibly call you Pat in the office and there’s already a Patrick in BP.’ Thinking of other things I could – and no doubt would – be called, I decided to accept this tag without protest. The secretaries’ nicknames were acutely observed and tended to become universally accepted. Compared to some, I was fortunate.

‘Can I help you, PJ?’ asked the girl with the eyes that laughed the most. Jo had already been introduced as my secretary and was thus a crucial partner in the adventure that was about to begin. I explained my predicament and she rummaged in a filing cabinet that I could not help noticing seemed to act as an overflow for her handbag as well as secure storage for sensitive papers.

‘We’ve got some examples here somewhere which you could copy …’ With a triumphant toss of chestnut hair and a jangle of bracelets, she handed me some files in the distinctive dark red of the Wales office. ‘When you’ve drafted it, I’ll type it for you. But we’d better get a move on. The Bag closes in half an hour.’

This was obviously an important piece of information. I checked the instinct to rush back to my desk and instead asked what the ‘Bag’ was. The girls looked at each other significantly. ‘That is the Bag.’ A manicured nail indicated a red plastic pouch the size of a small pillowcase. It sat in isolation on one of the less cluttered shelves next to a basket of papers on which I could glimpse Anne’s distinctive writing.

The Bag came to rule my life. It was the main means of written communi-cation with KP and so carried the whole catalogue of information, advice, pleading, cajoling and obfuscation which seemed to comprise our output. It also carried our letters of petition, contrition and – occasionally – resignation. These were mixed with bills, pills, fan mail, hate mail, and any private mail that had not already gone directly to the KP breakfast tray. Those envelopes had to be delivered unopened on pain of death, but it was by no means obvious which were entreaties from ardent suitors and which were complaints about office incompetence from loyal subjects. A secretary who could sniff the difference (sometimes literally) was worth her weight in gold.

In return the Bag welcomed us each morning with the overnight products of the royal pen. Schoolday comparisons with waiting for prep to be marked were inescapable, especially when alternative programmes such as the one I was struggling to draw up for the day in the West Country had been submitted for consideration.

The art, I discovered, was to submit the options in a way which led the Princess imperceptibly to the desired choice. The quickest way to learn that art was to watch what happened at the receiving end. Often, when I had been out with her all day, the Princess would find the Bag waiting in the car that came to collect us. It could be a tense moment. If we had enjoyed a good day, a bad Bag could take the shine off it in a second; and it took a very good Bag indeed to restore shine to a day that had been lousy.

She would snap the little plastic seal, pull back the heavy zip and delve inside. Balancing the inner cardboard file on her lap, she quickly sorted the papers into piles. Fashion catalogues or designers’ bills were dealt with first; then press cuttings; then loose minutes from the secretaries about things like therapists’ appointments or school events for the boys; then personal mail – some of it saved for private reading later; then real work – memos from me that required a decision, outline programmes, draft speeches, invitations, suggested letters … the list was endless.

She would hold out her hand for my pen, then go to work. She was quick and decisive – and expected me to be the same. This was at least partly to draw a distinction between herself and the Prince, whose capacity to sit on paperwork was legendary.

What worked best was to reduce a complicated question to a few important points – the bits she really had to know – and then offer two alternative answers. It was pretty basic staffwork, but quite intellectually satisfying. Soon I could anticipate fairly accurately her reaction to most questions. If I expected her to go for option A (‘Yes please’) but for reasons too complicated to explain I wanted her instead to pick option B (‘No thanks’), all I had to do was explain that A, while superficially attractive, risked controversy/conflict with another member of the royal family/bad press. ‘We don’t want to do that, do we, Patrick?’ she would say and I would look judicious, as if weighing up the pros and cons, and then agree with her. The pen would mark a big tick next to option B and everybody would be happy.

Mind you, she would not have been the Princess of Wales if there had not also been times when she would do the exact opposite out of spite. It seldom had anything to do with the pros and cons then. Eventually, however, I could sometimes predict these moods too. Then the procedure was reversed: all I had to do was extol the virtues of option A and she would automatically tick option B. It was a great game.

Much later, the game became less fun. The Princess bought a shredder and would unblushingly destroy papers that displeased her, then accuse me of not showing them to her in the first place. This enabled her to claim that she was not being supported, that her office (me) was incompetent, etc., etc. After a few such happy experiences, I learned to keep duplicates of anything that might end up in her shredder. I would then produce them when the original mysteriously ‘disappeared’. She hated that.

On my first day, of course, I knew none of this. Back at my temporary desk, I perused the files Jo had given me. One, labelled simply with ‘Merseyside’ and a date, was thick with papers and looked as if it had already made several arduous journeys to Liverpool in the rain. The other was pristine, contained two small sheets of pink paper and was labelled ‘Savoy lunch’.

‘Merseyside’ looked more promising, so, ignoring the background sounds of efficient equerries at work, I delved into its dog-eared contents. These read rather like a story whose plot assembles only gradually. Some characters – such as the Prince and Princess – we already know from previous novels in the series. Others we know by title if not yet as distinct personalities – the Lord Lieutenant, the Chief Constable, the local director of the Central Office of Information. Others again are complete new-comers whose place in the coming narrative is tantalizingly obscure. Will the leader of the Acorns Playgroup outbid the chairperson of the Drug Awareness workshop in the competition for the selector’s eye? Are the patronages they represent in or out of favour and will this affect their chances? Or will all be bulldozed aside by the requirement to fête the opening of a semiconductor factory whose oriental masters might repeat their largesse in another unemployment blackspot if given sufficient royal ‘face’?

Such musings crowded into my mind as I composed my first memo for the Bag. What style would be best? I had already seen a document addressed to the Queen in which, as precedent demands, the writer opened with the sonorous ‘Madam, With my humble duty …’ and, although I relished such verbal quaintness, it did not seem right for the lively Princess who had given me lunch. The examples I found in the ‘Merseyside’ file were more reassuring, opening with a simple ‘Sir’ or ‘Ma’am’ and proceeding to describe complex choices in simple, straightforward English. The only peculiarities I noticed were neat abbreviations for unwieldy royal titles (‘YRHes’ for ‘Your Royal Highnesses’) and a brisk respectfulness (‘As YRH will recall …’).

Eventually Jo forced me to hand over my meagre draft. Once printed on thick office stationery, its tentative phrases took on an air of authority which quite had me fooled until I saw my signature at the bottom. Early days, I thought to myself, as I saw it committed to the Bag which was then promptly sealed. ‘I’m going to the High Street during lunch so I can drop the Bag at KP nice and early. You never know, we might get it back this afternoon,’ said Jo, making for the door.

I returned to my corner and sought comfort in thoughts of lunch. Suddenly the phone on my desk rang. I went into shock. It had not rung before. What should I do now? Everybody else was already talking on their own phones, so this one was down to me.

It rang again, sounding louder. In my nervous, beginner’s state it even sounded royal. I picked up the receiver. ‘Hello?’ I said, clearing my throat. That didn’t sound very pukka, I thought.

‘Hello?’ said a man’s voice. It was crackly and faint, but vaguely familiar. ‘Who’s that?’ The voice sounded rather tetchy.

‘Who’s calling?’ I asked, trying to sound as if I was getting a grip.

‘It’s the Prince of Wales speaking,’ said the voice. Definitely tetchy. Panic.

‘Oh … sorry Sir. Um …’

Richard had finished his call and, from the far side of the room, his antennae had already picked up my plight. Dabbing a key on his fiercely complicated-looking phone, he cut in smoothly. ‘It’s Richard here, Sir …’

I imagined I could hear the relief in His Master’s Voice. What a great start, I thought.

The phone came to rule my life just as much as the Bag and, by its nature, it proved a shrill and insistent mistress. I admit now that I was too often ready to allow my patient secretaries to screen calls, so I was left at the end of the day with a callback list which reproachfully catalogued awkward conversations shirked and good news still untold.

My excuse – and it seemed a good one – was that I was fully occupied with priority calls, mostly from the Princess. She was a virtuoso with the instrument and I quickly came to measure the mood of the day by the first syllable of her morning greeting. It might have been telepathy, but I sometimes felt as if I knew just from the sound of the ringing tone that it was her. Taking a deep breath, I would pick up the receiver. Sometimes she would come straight through, calling from the car or her mobile. At other times she would be connected by the Palace switchboard.

The familiar voices of the imperturbable operators could spark a reply in neat adrenaline. I became quite good at interpreting the subtle nuances of their voices too. Some are indelibly linked in my mind to traumatic events of which they were the first harbingers. Invariably kind, often humorous, sometimes wonderfully motherly, they must have assisted unwittingly at many executions. On a shamefully rare visit to their subterranean den, I was not surprised to see knitting in progress.