По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

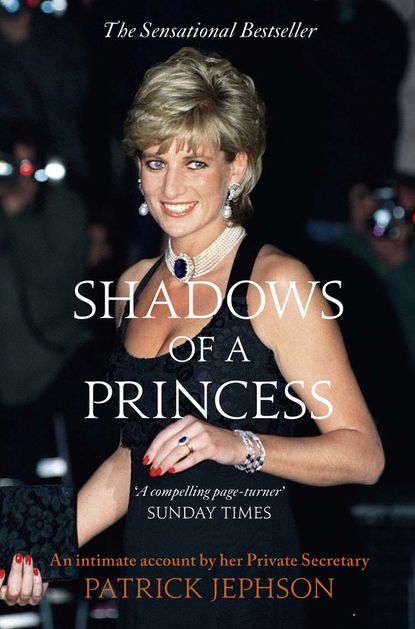

Shadows of a Princess

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Megalomania is no more attractive for being played out on a small scale, at least from the viewpoint of those in the firing line, and they come no smaller than the pieces on the nursery floor whose time is up. Their sin might be no more than Richard’s – a perceived allegiance to the ‘other side’. Like his, it need have no bearing on professional competence. It could be merely that they knew too much (whatever their proven discretion), or that they laughed too little (however quietly dedicated), or that they spoke too much sense (however loyally expressed), or that they shared too little in her misery (whatever the cause of their happiness). Or – the worst crime of all – they had just become boring. An exaggeration? Hardly. As her chosen instrument I officiated at too many of these playroom executions to doubt her intentions.

I remember the first. In 1990, a secretary convicted in absentia of most of the high crimes listed above stood at my desk awaiting judgement. She knew the sack was hovering over her. As Wodehouse would say, she could practically hear the beating of its wings. This was part of the process. Very few victims were given their P45 out of the blue. Usually there was a softening-up period in which the transgressor would be frozen out of the Princess’s affections. The warning signs were obvious.

‘Is Charlotte on holiday again?’ she would say to me.

‘Yes she is, Ma’am. In fact I sent you a note about it. You said you were quite happy. Is there a problem?’

‘Oh no,’ – innocently – ‘but she does seem to be having rather a lot of holidays … and we’re so busy. It just seems so unfair on everybody else …’ Her voice would trail off, leaving me to pick up a fairly typical clutch of veiled barbs:

- Charlotte is lazy. She may be taking no more than her holiday entitlement – or even less, it was not uncommon – but this inconvenient fact can be overlooked. Now, by royal command, she is lazy.

- I am incompetent. Why have I allowed a secretary to go on holiday when the diary is so busy? The fact that there is actually a lull in activity – hence the conscientious Charlotte’s decision to take leave this week – can also be overlooked. This is a pincer movement, designed to intimidate me from taking the victim’s side. Too often, I confess, I allowed it to silence me.

- The Princess, by contrast, is working very hard. You could dispute this, but only if you were ready to lose your job. In royal circles it is accepted as a matter of sacred truth that, by definition, all members of our modern royal family work terribly hard all the time – even if a cursory analysis of their daily existence might call this into question.

- She cares about the extra workload now shouldered by the other staff. Here was a classic example of ‘caring Di’ behaviour that was not quite what it seemed. By expressing concern for her remaining hard-working staff, she was actually isolating the absentee and preparing the ground for the execution to follow.

For added emphasis, the rest of the staff – even those notoriously less dedicated than Charlotte – would receive redoubled praise and interest from the Princess, now advancing on them with a careless laugh and a prepared ration of girly gossip.

It took a curious form of toadying to enjoy favours thus received, but some managed it. For most, though, it was enough just to keep your head down and hope that it was not going to be your turn as victim just yet. Perhaps it would not come at all. Such comforting thoughts came easily when the big blue eyes looked on you favourably. The gaze seemed full of trust and expectation then; quite incapable of measuring you for your professional coffin.

Being frozen out was a lingering death in which messages would be unacknowledged, memos ignored or even destroyed, and mere physical existence ‘blanked’. This was especially easy when chances to ignore a desperate bow or curtsy were so abundant. For people chosen for their sense of loyalty, it was a torture few could bear for long. Many saved the Princess the trouble of sacking them and quietly took their leave, usually with great dignity.

I looked at the unhappy secretary standing by my desk, and she looked back at me. We both knew she had done nothing to warrant her dismissal. We both knew life would be unbearable for her if she stayed. I could not contain my revulsion; I had to get outside. I took her for a walk round Green Park and asked her how the parting could be made easier for her. References, medical insurance, gratuity – I promised, and delivered, them all. Her quiet tears diminished me even further.

I ran into her again some years later. Being the sort of person she was, she had quite forgiven my part in the shameful charade. Curiously, and not untypically, she had forgiven the Princess too. It is an astonishing fact that such forgivability was freely conferred on the Princess by a sacked secretary and a besotted world. It was surely her greatest and most exploited talent.

The executions continued throughout my time with the Princess: two ladies-in-waiting, a butler, a cook, three secretaries, a chauffeur, a housemaid, two dressers, and others I cannot now recall. Most went quietly. When the time came, few had any regrets. The Princess saw to that, which I suppose was a form of unintentional kindness, if a cruel one.

In its extreme forms the softening-up process could be actively hostile. In one case, the Princess started a rumour about a secretary’s personal life, waited for it to gain currency and then cited it as damning evidence of unsuitability. (The secretary left, but only out of disgust.) In another she launched a bitterly resentful assault on a junior member of her staff whom she observed enjoying a happy relationship with another. (They are now married.)

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: