По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

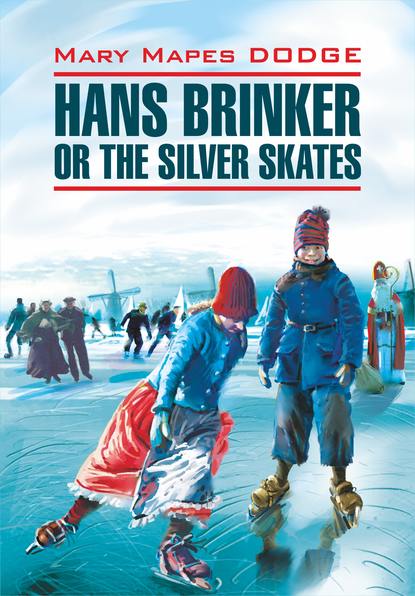

Hans Brinker, or the Silver Skates / Серебряные коньки. Книга для чтения на английском языке

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Broek, with its quiet, spotless streets, its frozen rivulets, its yellow brick pavements and bright wooden houses, was nearby. It was a village where neatness and show were in full blossom, but the inhabitants seemed to be either asleep or dead.

Not a footprint marred the sanded paths where pebbles and seashells lay in fanciful designs. Every window shutter was tightly closed as though air and sunshine were poison, and the massive front doors were never opened except on the occasion of a wedding, a christening, or a funeral.

Serene clouds of tobacco smoke were floating through hidden corners, and children, who otherwise might have awakened the place, were studying in out-of-the-way corners or skating upon the neighboring canal. A few peacocks and wolves stood in the gardens, but they had never enjoyed the luxury of flesh and blood. They were made out of boxwood hedges[70 - boxwood hedges – подстриженные в виде животных буковые деревья] and seemed to be guarding the grounds with a sort of green ferocity. Certain lively automata, ducks, women, and sportsmen, were stowed away in summer houses, waiting for the spring-time when they could be wound up and rival their owners in animation; and the shining tiled roofs, mosaic courtyards, and polished house trimmings flashed up a silent homage to the sky, where never a speck of dust could dwell.

Hans glanced toward the village, as he shook his silver kwartjes and wondered whether it were really true, as he had often heard, that some of the people of Broek were so rich that they used kitchen utensils of solid gold.

He had seen Mevrouw van Stoop’s sweet cheeses in market, and he knew that the lofty dame earned many a bright silver guilder in selling them. But did she set the cream to rise in golden pans? Did she use a golden skimmer? When her cows were in winter quarters, were their tails really tied up with ribbons?

These thoughts ran through his mind as he turned his face toward Amsterdam, not five miles away, on the other side of the frozen Y[71 - Y – произносится как eye; рукав Зёйдерзее (примеч. авт.)]. The ice upon the canal was perfect, but his wooden runners, so soon to be cast aside, squeaked a dismal farewell as he scraped and skimmed along.

When crossing the Y, whom should he see skating toward him but the great Dr. Boekman, the most famous physician and surgeon in Holland. Hans had never met him before, but he had seen his engraved likeness in many of the shop windows in Amsterdam. It was a face that one could never forget. Thin and lank, though a born Dutchman, with stern blue eyes, and queer compressed lips that seemed to say “No smiling permitted[72 - No smiling permitted – (шутл.) Улыбаться запрещается],” he certainly was not a very jolly or sociable-looking personage, nor one that a well-trained boy would care to accost unbidden.

But Hans WAS bidden, and that, too, by a voice he seldom disregarded – his own conscience.

“Here comes the greatest doctor in the world,” whispered the voice. “God has sent him. You have no right to buy skates when you might, with the same money, purchase such aid for your father!”

The wooden runners gave an exultant squeak. Hundreds of beautiful skates were gleaming and vanishing in the air above him. He felt the money tingle in his fingers. The old doctor looked fearfully grim and forbidding. Hans’s heart was in his throat, but he found voice enough to cry out, just as he was passing, “Mynheer Boekman!”

The great man halted and, sticking out his thin underlip, looked scowling about him.

Hans was in for it now.

“Mynheer,” he panted, drawing close to the fierce-looking doctor, “I knew you could be none other than the famous Boekman. I have to ask a great favor – ”

“Hump!” muttered the doctor, preparing to skate past the intruder. “Get out of the way. I’ve no money – never give to beggars[73 - never give to beggars – (разг.) я не подаю нищим].”

“I am no beggar, mynheer,” retorted Hans proudly, at the same time producing his mite of silver with a grand air. “I wish to consult you about my father. He is a living man but sits like one dead. He cannot think. His words mean nothing, but he is not sick. He fell on the dikes.”

“Hey? What?” cried the doctor, beginning to listen.

Hans told the whole story in an incoherent way, dashing off a tear once or twice as he talked, and finally ending with an earnest “Oh, do see him, mynheer. His body is well – it is only his mind. I know that this money is not enough, but take it, mynheer. I will earn more, I know I will. Oh! I will toil for you all my life, if you will but cure my father!”

What was the matter with the old doctor? A brightness like sunlight beamed from his face. His eyes were kind and moist; the hand that had lately clutched his cane, as if preparing to strike, was laid gently upon Hans’s shoulder.

“Put up your money, boy, I do not want it. We will see your father. It’s hopeless, I fear. How long did you say?”

“Ten years, mynheer,” sobbed Hans, radiant with sudden hope.

“Ah! a bad case, but I shall see him. Let me think. Today I start for Leyden, to return in a week, then you may expect me. Where is it?”

“A mile south of Broek, mynheer, near the canal. It is only a poor, broken-down hut. Any of the children thereabout can point it out to your honor,” added Hans with a heavy sigh. “They are all half afraid of the place; they call it the idiot’s cottage.”

“That will do[74 - That will do – (разг.) Хватит; достаточно],” said the doctor, hurrying on with a bright backward nod at Hans. “I shall be there. A hopeless case,” he muttered to himself, “but the boy pleases me. His eye is like my poor Laurens’s. Confound it, shall I never forget that young scoundrel!” And, scowling more darkly than ever, the doctor pursued his silent way.

Again Hans was skating toward Amsterdam on the squeaking wooden runners; again his fingers tingled against the money in his pocket; again the boyish whistle rose unconsciously to his lips.

Shall I hurry home, he was thinking, to tell the good news, or shall I get the wafles and the new skates first? Whew! I think I’ll go on!

And so Hans bought the skates.

Introducing Jacob Poot and His Cousin

Hans and Gretel had a fine frolic early on that Saint Nicholas’s Eve. There was a bright moon, and their mother, though she believed herself to be without any hope of her husband’s improvement, had been made so happy at the prospect of the meester’s visit, that she yielded to the children’s entreaties for an hour’s skating before bedtime.

Hans was delighted with his new skates and, in his eagerness to show Gretel how perfectly they “worked,” did many things upon the ice that caused the little maid to clasp her hands in solemn admiration. They were not alone, though they seemed quite unheeded by the various groups assembled upon the canal.

The two Van Holps and Carl Schummel were there, testing their fleetness to the utmost[75 - to the utmost – (разг.) изо всех сил]. Out of four trials Peter van Holp had won three times. Consequently Carl, never very amiable, was in anything but a good humor[76 - was in anything but a good humor – (разг.) был в плохом настроении]. He had relieved himself by taunting young Schimmelpenninck, who, being smaller than the others, kept meekly near them without feeling exactly like one of the party, but now a new thought seized Carl, or rather he seized the new thought and made an onset upon his friends.

“I say, boys, let’s put a stop to those young ragpickers from the idiot’s cottage joining the race. Hilda must be crazy to think of it. Katrinka Flack and Rychie Korbes are furious at the very idea of racing with the girl; and for my part, I don’t blame them. As for the boy, if we’ve a spark of manhood in us, we will scorn the very idea of – ”

“Certainly we will!” interposed Peter van Holp, purposely mistaking Carl’s meaning. “Who doubts it? No fellow with a spark of manhood in him would refuse to let in two good skaters just because they were poor!”

Carl wheeled about savagely. “Not so fast, master! And I’d thank you not to put words in other people’s mouths[77 - not to put words in other people’s mouths – (разг.) не надо говорить за других]. You’d best not try it again.”

“Ha, ha!” laughed little Voostenwalbert Schimmelpenninck, delighted at the prospect of a fight, and sure that, if it should come to blows[78 - if it should come to blows – (разг.) если дело дойдет до драки], his favorite Peter could beat a dozen excitable fellows like Carl.

Something in Peter’s eye made Carl glad to turn to a weaker offender. He wheeled furiously upon Voost.

“What are you shrieking about, you little weasel? You skinny herring you, you little monkey with a long name for a tail!”

Half a dozen bystanders and byskaters set up an applauding shout at this brave witticism; and Carl, feeling that he had fairly vanquished his foes, was restored to partial good humor. He, however, prudently resolved to defer plotting against Hans and Gretel until some time when Peter should not be present.

Just then, his friend, Jacob Poot, was seen approaching. They could not distinguish his features at first, but as he was the stoutest boy in the neighborhood, there could be no mistaking his form.

“Hello! Here comes Fatty!” exclaimed Carl. “And there’s someone with him, a slender fellow, a stranger.”

“Ha! ha! That’s like good bacon,” cried Ludwig. “A streak of lean and a streak of fat.”

“That’s Jacob’s English cousin,” put in Master Voost, delighted at being able to give the information. “That’s his English cousin, and, oh, he’s got such a funny little name – Ben Dobbs. He’s going to stay with him until after the grand race.”

All this time the boys had been spinning, turning, rolling, and doing other feats upon their skates, in a quiet way, as they talked, but now they stood still, bracing themselves against the frosty air as Jacob Poot and his friend drew near.

“This is my cousin, boys,” said Jacob, rather out of breath. “Benjamin Dobbs. He’s a John Bull[79 - a John Bull – Джон Буль, шутливое прозвище англичан, получившее широкое распространение; впервые употреблено в сатирическом памфлете Дж. Арбетнота (1667– 1735) «Тяжба без конца, или История Джона Буля»] and he’s going to be in the race.”

All crowded, boy-fashion, about the newcomers. Benjamin soon made up his mind that the Hollanders, notwithstanding their queer gibberish, were a fine set of fellows.

If the truth must be told, Jacob had announced his cousin as Penchamin Dopps, and called him a Shon Pull, but as I translate every word of the conversation of our young friends, it is no more than fair to mend their little attempts at English. Master Dobbs felt at first decidedly awkward among his cousin’s friends. Though most of them had studied English and French, they were shy about attempting to speak either, and he made very funny blunders when he tried to converse in Dutch. He had learned that vrouw meant wife; and ja, yes; and spoorweg, railway; kanaals, canals; stoomboot, steamboat; ophaalbruggen, drawbridges; buiten plasten, country seats; mynheer, mister; tweegevegt, duel or “two fights”; koper, copper; zadel, saddle; but he could not make a sentence out of these, nor use the long list of phrases he had learned in his “Dutch dialogues.” The topics of the latter were fine, but were never alluded to by the boys. Like the poor fellow who had learned in Ollendorf to ask in faultless German, “Have you seen my grandmother’s red cow?” and, when he reached Germany, discovered that he had no occasion to inquire after that interesting animal, Ben found that his book-Dutch did not avail him as much as he had hoped. He acquired a hearty contempt for Jan van Gorp, a Hollander who wrote a book in Latin to prove that Adam and Eve spoke Dutch, and he smiled a knowing smile when his uncle Poot assured him that Dutch “had great likeness mit Zinglish but it vash much petter languish, much petter.”

However, the fun of skating glides over all barriers of speech. Through this, Ben soon felt that he knew the boys well, and when Jacob (with a sprinkling of French and English for Ben’s benefit) told of a grand project they had planned, his cousin could now and then put in a ja, or a nod, in quite a familiar way.

The project WAS a grand one, and there was to be a fine opportunity for carrying it out; for, besides the allotted holiday of the Festival of Saint Nicholas, four extra days were to be allowed for a general cleaning of the schoolhouse.

Jacob and Ben had obtained permission to go on a long skating journey – no less a one than from Broek to The Hague, the capital of Holland, a distance of nearly fifty miles[80 - fifty miles – в этой книге все расстояния даны в английских милях (1,6 км); голландская миля в четыре с лишним раза длиннее (примеч. авт.)]!

“And now, boys,” added Jacob, when he had told the plan, “who will go with us?”

“I will! I will!” cried the boys eagerly.