По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

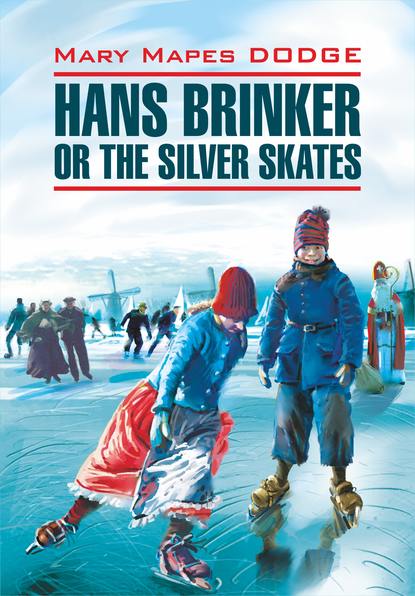

Hans Brinker, or the Silver Skates / Серебряные коньки. Книга для чтения на английском языке

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

A memory of some such scene crossed her son’s mind now, for, after giving a heavy sigh, and flipping a crumb of wax at Gretel across the table, he said, “Aye, Mother, you have done bravely to keep it – many a one would have tossed it off for gold long ago.”

“And more shame for them!” exclaimed the dame indignantly. “I would not do it. Besides, the gentry are so hard on us poor folks that if they saw such a thing in our hands, even if we told all, they might suspect the father of – ”

Hans flushed angrily.

“They would not DARE to say such a thing, Mother! If they did, I’d…”

He clenched his fist and seemed to think that the rest of his sentence was too terrible to utter in her presence.

Dame Brinker smiled proudly through her tears at this interruption.

“Ah, Hans, thou’rt a true, brave lad. We will never part company with the watch. In his dying hour the dear father might wake and ask for it.”

“Might WAKE, Mother!” echoed Hans. “Wake – and know us?”

“Aye, child,” almost whispered his mother, “such things have been.”

By this time Hans had nearly forgotten his proposed errand to Amsterdam. His mother had seldom spoken so familiarly to him. He felt himself now to be not only her son, but her friend, her adviser:

“You are right, Mother. We must never give up the watch. For the father’s sake we will guard it always. The money, though, may come to light[57 - may come to light – (разг.) могут найтись] when we least expect it.”

“Never!” cried Dame Brinker, taking the last stitch from her needle with a jerk and laying the unfinished knitting heavily upon her lap. “There is no chance! One thousand guilders – and all gone in a day! One thousand guilders. Oh, what ever DID become of them? If they went in an evil way, the thief would have confessed it on his dying bed. He would not dare to die with such guilt on his soul!”

“He may not be dead yet,” said Hans soothingly. “Any day we may hear of him.”

“Ah, child,” she said in a changed tone, “what thief would ever have come HERE? It was always neat and clean, thank God, but not fine, for the father and I saved and saved that we might have something laid by. ‘Little and often soon fills the pouch.’ We found it so, in truth. Besides, the father had a goodly sum already, for service done to the Heernocht lands, at the time of the great inundation. Every week we had a guilder left over, sometimes more; for the father worked extra hours and could get high pay for his labor. Every Saturday night we put something by, except the time when you had the fever, Hans, and when Gretel came. At last the pouch grew so full that I mended an old stocking and commenced again. Now that I look back, it seems that the money was up to the heel in a few sunny weeks. There was great pay in those days if a man was quick at engineer work. The stocking went on filling with copper and silver – aye, and gold. You may well open your eyes, Gretel. I used to laugh and tell the father it was not for poverty I wore my old gown. And the stocking went on filling, so full that sometimes when I woke at night, I’d get up, soft and quiet, and go feel it in the moonlight. Then, on my knees, I would thank our Lord that my little ones could in time get good learning, and that the father might rest from labor in his old age. Sometimes, at supper, the father and I would talk about a new chimney and a good winter room for the cow, but my man had finer plans even than that. ‘A big sail,’ says he, ‘catches the wind – we can do what we will soon,’ and then we would sing together as I washed my dishes. Ah, ‘a smooth wind makes an easy rudder[58 - a smooth wind makes an easy rudder – (уст.) на тихом море легко за штурвалом].’ Not a thing vexed me from morning till night. Every week the father would take out the stocking and drop in the money and laugh and kiss me as we tied it up together. Up with you, Hans! There you sit gaping, and the day a-wasting!” added Dame Brinker tartly, blushing to find that she had been speaking too freely to her boy. “It’s high time you were on your way.[59 - It’s high time you were on your way. – (разг.) Тебе уже давно пора отправляться в путь.]”

Hans had seated himself and was looking earnestly into her face. He arose and, in almost a whisper, asked, “Have you ever tried, Mother?”

She understood him.

“Yes, child, often. But the father only laughs, or he stares at me so strange that I am glad to ask no more. When you and Gretel had the fever last winter, and our bread was nearly gone, and I could earn nothing, for fear you would die while my face was turned[60 - while my face was turned – (разг.) стоит мне только отвернуться], oh! I tried then! I smoothed his hair and whispered to him soft as a kitten, about the money – where it was, who had it? Alack! He would pick at my sleeve and whisper gibberish till my blood ran cold. At last, while Gretel lay whiter than snow, and you were raving on the bed, I screamed to him – it seemed as if he MUST hear me – ‘Raff, where is our money? Do you know aught of the money, Raff? The money in the pouch and the stocking, in the big chest?’ But I might as well have talked to a stone. I might as – ”

The mother’s voice sounded so strange, and her eye was so bright, that Hans, with a new anxiety, laid his hand upon her shoulder.

“Come, Mother,” he said, “let us try to forget this money. I am big and strong. Gretel, too, is very quick and willing. Soon all will be prosperous with us again.[61 - Soon all will be prosperous with us again. – (уст.) Скоро мы снова разбогатеем.] Why, Mother, Gretel and I would rather see thee bright and happy than to have all the silver in the world, wouldn’t we, Gretel?”

“The mother knows it,” said Gretel, sobbing.

Sunbeams

Dame Brinker was startled at her children’s emotion; glad, too, for it proved how loving and true they were.

Beautiful ladies in princely homes often smile suddenly and sweetly, gladdening the very air around them, but I doubt if their smile be more welcome in God’s sight than that which sprang forth to cheer the roughly clad boy and girl in the humble cottage. Dame Brinker felt that she had been selfish. Blushing and brightening, she hastily wiped her eyes and looked upon them as only a mother can.

“Hoity! Toity! Pretty talk we’re having, and Saint Nicholas’s Eve almost here! What wonder the yarn pricks my fingers! Come, Gretel, take this cent[62 - cent – голландский цент стоит меньше половины американского цента (примеч. авт.)], and while Hans is trading for the skates you can buy a wafle in the marketplace.”

“Let me stay home with you, Mother,” said Gretel, looking up with eyes that sparkled through their tears. “Hans will buy me the cake.”

“As you will, child, and Hans – wait a moment. Three turns of this needle will finish this toe, and then you may have as good a pair of hose as ever were knitted (owning the yarn is a grain too sharp) to sell to the hosier on the Harengracht[63 - Harengracht – улица в Амстердаме (примеч. авт.)]. That will give us three quarter-guilders if you make good trade; and as it’s right hungry weather, you may buy four wafles. We’ll keep the Feast of Saint Nicholas after all.”

Gretel clapped her hands. “That will be fine! Annie Bouman told me what grand times they will have in the big houses tonight. But we will be merry too. Hans will have beautiful new skates – and then there’ll be the wafles! Oh! Don’t break them, brother Hans. Wrap them well, and button them under your jacket very carefully.”

“Certainly,” replied Hans, quite gruff with pleasure and importance.

“Oh! Mother!” cried Gretel in high glee, “soon you will be busied with the father, and now you are only knitting. Do tell us all about Saint Nicholas!”

Dame Brinker laughed to see Hans hang up his hat and prepare to listen. “Nonsense, children,” she said. “I have told it to you often.”

“Tell us again! Oh, DO tell us again!” cried Gretel, throwing herself upon the wonderful wooden bench that her brother had made on the mother’s last birthday. Hans, not wishing to appear childish, and yet quite willing to hear the story, stood carelessly swinging his skates against the fireplace.

“Well, children, you shall hear it, but we must never waste the daylight again in this way. Pick up your ball, Gretel, and let your sock grow as I talk. Opening your ears needn’t shut your fingers.[64 - Opening your ears needn’t shut your fingers. – (посл.) Уши навостри, но без дела не сиди.] Saint Nicholas, you must know, is a wonderful saint. He keeps his eye open for the good of sailors, but he cares most of all for boys and girls. Well, once upon a time, when he was living on the earth, a merchant of Asia sent his three sons to a great city, called Athens, to get learning.”

“Is Athens in Holland, Mother?” asked Gretel.

“I don’t know, child. Probably it is.”

“Oh, no, Mother,” said Hans respectfully. “I had that in my geography lessons long ago. Athens is in Greece.”

“Well,” resumed the mother, “what matter? Greece may belong to the king, for aught we know. Anyhow, this rich merchant sent his sons to Athens. While they were on their way, they stopped one night at a shabby inn, meaning to take up their journey in the morning. Well, they had very fine clothes – velvet and silk, it may be, such as rich folks’ children all over the world think nothing of wearing – and their belts, likewise, were full of money. What did the wicked landlord do but contrive a plan to kill the children and take their money and all their beautiful clothes himself. So that night, when all the world was asleep, he got up and killed the three young gentlemen.”

Gretel clasped her hands and shuddered, but Hans tried to look as if killing and murder were everyday matters to him.

“That was not the worst of it[65 - That was not the worst of it – (разг.) И это было не самое страшное],” continued Dame Brinker, knitting slowly and trying to keep count of her stitches as she talked. “That was not near the worst of it. The dreadful landlord went and cut up the young gentlemen’s bodies into little pieces and threw them into a great tub of brine, intending to sell them for pickled pork!”

“Oh!” cried Gretel, horror-stricken, though she had often heard the story before. Hans was still unmoved and seemed to think that pickling was the best that could be done under the circumstances.

“Yes, he pickled them, and one might think that would have been the last of the young gentlemen. But no. That night Saint Nicholas had a wonderful vision, and in it he saw the landlord cutting up the merchant’s children. There was no need of his hurrying, you know, for he was a saint, but in the morning he went to the inn and charged the landlord with murder. Then the wicked landlord confessed it from beginning to end and fell down on his knees, begging forgiveness. He felt so sorry for what he had done that he asked the saint to bring the young masters to life.”

“And did the saint do it?” asked Gretel, delighted, well knowing what the answer would be.

“Of course he did. The pickled pieces flew together in an instant, and out jumped the young gentlemen from the brine tub. They cast themselves at the feet of Saint Nicholas, and he gave them his blessing, and – oh! mercy on us, Hans, it will be dark before you get back if you don’t start this minute!”

By this time Dame Brinker was almost out of breath and quite out of commas. She could not remember when she had seen the children idle away an hour of daylight in this manner, and the thought of such luxury quite appalled her. By way of compensation[66 - By way of compensation – (зд.) Стремясь наверстать упущенное время] she now flew about the room in extreme haste. Tossing a block of peat upon the fire, blowing invisible fire from the table, and handing the finished hose to Hans, all in an instant…

“Come, Hans,” she said as her boy lingered by the door. “What keeps thee?”

Hans kissed his mother’s plump cheek, rosy and fresh yet, in spite of all her troubles.

“My mother is the best in the world, and I would be right glad to have a pair of skates, but” – and as he buttoned his jacket he looked, in a troubled way, toward a strange figure crouching by the hearthstone – “if my money would bring a meester[67 - meester – так малообразованные голландцы называли доктора (примеч. авт.)] from Amsterdam to see the father, something might yet be done.”

“A meester would not come, Hans, for twice that money, and it would do no good if he did[68 - it would do no good if he did – (разг.) даже если он и придет, это не поможет]. Ah, how many guilders I once spent for that, but the dear, good father would not waken. It is God’s will. Go, Hans, and buy the skates.”

Hans started with a heavy heart, but since the heart was young and in a boy’s bosom, it set him whistling in less than five minutes. His mother had said “thee” to him, and that was quite enough to make even a dark day sunny. Hollanders do not address each other, in affectionate intercourse, as the French and Germans do. But Dame Brinker had embroidered for a Heidelberg[69 - Heidelberg – Гейдельберг, город в Баден-Вюртемберге, в котором расположен один из старейших университетов (основан в 1386 г.)] family in her girlhood, and she had carried its thee and thou into her rude home, to be used in moments of extreme love and tenderness.

Therefore, “What keeps thee, Hans?” sang an echo song beneath the boy’s whistling and made him feel that his errand was blest.

Hans Has His Way