По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

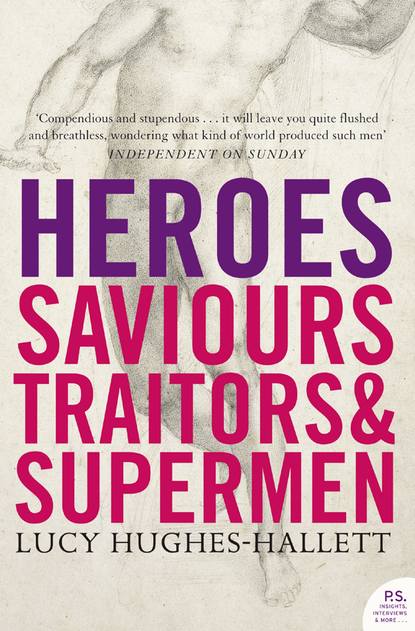

Heroes: Saviours, Traitors and Supermen

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

In Athens political debate was urgent, incessant, bafflingly inconclusive. The political process was obstructed and complicated at every turn by envy, corruption, and blackmail. The tenure of any office was brief. There was no certainty, no continuity, no easy-going reliance on precedent. Every principle, and every practical detail, was to be debated and voted upon. This edgy insistence on examining every question afresh each time it arose is one of the things that made Athens so exhilarating a society and gave it its extraordinary intellectual and political vitality. But it imposed a burden on the citizens that exasperated or frightened many, and which others found simply too great to bear. In the summer of 408 BC, when Alcibiades descended on Athens surrounded by the golden aura of the conquering hero, as splendid as one of those godlike men whom Aristotle judged fully entitled to enslave their fellows, there were many who entertained the fantasy of surrendering their exhausting freedom to him. People came to him and begged him to ‘rid them of those (#litres_trial_promo) loud-mouthed wind-bags who were the bane of the city’, to silence the ceaseless, bewildering play of argument and counter-argument for which the entire city was the stage by seizing absolute power. In an extraordinary frenzy of self-abasement, people begged him to make himself dictator, to ‘sweep away decrees and laws as he thought fit’, to overturn the constitution and wipe out all opposition, thus relieving the demoralized and insecure citizens of the awful burden of their liberty.

Alcibiades did not respond to the invitation. He had work to do elsewhere. The Spartan fleet under its formidable new commander Lysander was lying at Ephesus, a menace to the Athenian colonies. The Assembly granted Alcibiades all the men and ships he required, even allowing him the unprecedented honour of choosing his own fellow generals. Their generosity was expressive of the people’s adulation of their new commander-in-chief. Besides, the Assembly’s more thoughtful members were probably anxious to speed him on his way. ‘We do not know (#litres_trial_promo) what Alcibiades himself thought of a dictatorship,’ writes Plutarch, ‘but certainly the leading citizens at this time were frightened of it.’ They mistook their man. The insatiable ambition Socrates had seen in his disciple was not for stay-at-home executive power, but for world-bestriding glory. Soon after the Eleusinian festival, just four months after he had entered the city, Alcibiades left Athens for ever.

He had seduced the people and alarmed the leading democrats, but he had not won over the gods. The day on which he landed in Athens to be so rapturously received was the unluckiest of the year, the day when the image of Athena on the Acropolis was veiled for secret purification rites. Perhaps those citizens hostile to Alcibiades pointed out the inauspicious circumstance at the time, to be ignored by the ecstatic majority. Perhaps it was only with hindsight that people were to remember it as a sign of what was to come. At the zenith of his popularity, the city’s patron goddess turned her face away from him. Only months later the city’s people were, as though in imitation, to withdraw their favour.

‘If ever a man (#litres_trial_promo) was destroyed by his own high reputation,’ wrote Plutarch, ‘it was Alcibiades.’ He was now expected to work miracles; and when he failed to do so the lethally volatile democratic Assembly began to grumble and to doubt his loyalty, ‘for they were convinced that nothing which he seriously wanted to achieve was beyond him’. He sailed to Andros, where he established a fort but failed to take the city. When he arrived at Notium in Asia Minor, across the bay from the Peloponnesian fleet at Ephesus, he was unable to lure Lysander out of the safety of the harbour. The oarsmen began to defect: the Spartans, now subsidized by the Persian Prince Cyrus, were able to offer them 25 per cent more pay than the Athenians. Alcibiades, foreseeing a long and expensive wait before he could force a decisive engagement, sailed off to raise funds elsewhere, leaving the main fleet under the temporary command of Antiochus, the pilot of his ship. It was a controversial appointment. Antiochus was a professional sailor, not one of the aristocratic trierarchs or amateur captains who, though probably less competent, were his social superiors and who would have seen themselves as outranking him. He had known and served Alcibiades for nearly twenty years, ever since he had caught his future commander’s errant quail for him in the Assembly. Alcibiades’ decision to place him in command was audacious, unconventional and, as it turned out, calamitous. In Alcibiades’ absence, and in defiance of his explicit order, Antiochus provoked a battle for which he was totally unprepared. Lysander put the Athenians to flight, sinking twenty ships. Antiochus was killed. Alcibiades raced back to Notium and attempted, unsuccessfully, to induce Lysander to fight again. Only a brilliant victory could have saved him, but it was not forthcoming.

When the news reached Athens, all the old accusations against him were revived. He was arrogant. He was depraved. He was untrustworthy. The people who, only months before, had been ready to give up their political rights for the privilege of being his subjects now turned on him with a fury as irrational as their adulation had been. It was alleged that he intended to make himself a tyrant. It was pointed out that he had built a castle in Thrace – why, asked his accusers, would a loyal Athenian need such a bolt-hole? The appointment of Antiochus, unquestionably a mistake, was presented as evidence of his wicked frivolity. ‘He had entrusted (#litres_trial_promo) the command’, said one of his accusers, ‘to men who had won his confidence simply through their capacity for drinking and spinning sailors’ yarns, because he wanted to leave himself free to cruise about raising money and indulging in debauchery and drunken orgies with the courtesans of Abydos and Ionia.’ He was accused of accepting a bribe from the King of Cyme, a city he had failed to take. None of the charges against him were substantiated. They did not need to be. After all, in 417 BC, the Athenians had come close to banishing him by ostracism for no reason at all except that he had grown too great. Now new generals were elected, one of whom was ordered to sail east and relieve Alcibiades of his command. On hearing that his city, whom he had so grossly betrayed but to whom he had since done such great service, had once again rejected him Alcibiades left the fleet, left the Greek world entirely, and, Coriolanus-like, sought a world elsewhere.

Taking only one ship, he sailed away northward to Thrace, where he had indeed had the foresight to acquire not one, but three castles. There, among the lawless barbarians, he recruited a private army and embarked upon the life of a brigand chief, a robber baron, preying upon his neighbours and taking prisoners for ransom. Adaptable as ever, he assumed the habits of his new countrymen, winning the friendship of the tribal chieftains by matching them, according to Cornelius Nepos, ‘in drunkenness and lust (#litres_trial_promo)’. Perhaps, as the historian and novelist Peter Green has suggested, this was the debauchery attendant on despair; or perhaps it was the zestful beginning of yet another new life. We shall see how Rodrigo Díaz, the Cid, another outcast hero who grew too great for the state he served, was to begin again as a bandit in the badlands of eleventh-century Spain and ultimately to make himself prince of a great city. After two years in Thrace, Alcibiades was to boast that he was treated there ‘like a king’.

In Athens meanwhile, as disaster followed upon disaster, he gradually acquired the mystique of a king over the water, a once and perhaps future redeemer of his native city. A year after the beginning of his second exile Aristophanes had a character in The Frogs say of Alcibiades that the Athenians ‘yearn for him, they hate him, but they want to have him back’. His history was to touch theirs just once more, in an encounter that yet again identified him as the man who could have saved Athens if only Athens had allowed him to do so.

In 405 BC, on the eve of the disastrous battle of Aegosopotami, he appeared, a troubling deus ex machina, in the Athenian camp. The Athenian and Spartan fleets were drawn up facing each other in the narrowest part of the Hellespont, the Athenians being on the Thracian shore, only a few miles from his stronghold. Alcibiades, uninvited and unexpected, came riding in and demanded a meeting with the generals. He pointed out to them that their position was dangerously exposed, and too far from their source of supplies. He advised them to move and offered them the armies of two Thracian kings on whom he could rely. The Athenian generals would not listen. Perhaps they remembered how he had once offered to deliver Persian money and Phoenician ships and failed to do so. Perhaps they thought of how Thrasybulus had been eclipsed and, as Diodorus suggests, were jealously protecting their own reputations, fearing ‘that if they were defeated (#litres_trial_promo) they themselves would get the blame, but that the credit for any success would go to Alcibiades’. Whatever their motives, they turned him away rudely saying, ‘We are in command (#litres_trial_promo) now, not you.’ As he rode out of the camp, Alcibiades told his companions that had he not been so outrageously insulted the Spartans would have lost all their ships. Some thought this boast mere bravado, but many, including some modern historians, have believed him. Rejected for the third time, he galloped away. At Aegosopotami the Athenian fleet was utterly destroyed. The survivors, including all but one of the generals, were slaughtered. A few months later Athens fell.

For the last year of his life Alcibiades was a fugitive. The Spartans still wanted him dead. Their victory rendered coastal Thrace unsafe for him. He withdrew into the interior, leaving behind the bulk of his possessions, which the neighbouring chieftains promptly looted. As he travelled inland he was set upon and robbed of his remaining belongings but he managed to escape capture and made his way, armed now only with his reputation and his miracle-working charm, to the headquarters of the Persian Satrap Pharnabazus. Once more, as when he arrived at Tissaphernes’ court, ‘he so captivated (#litres_trial_promo) Pharnabazus that he became the Persian’s closest friend’. Graciously, the Satrap granted him the Phrygian city of Grynium and all its revenues. He had found a refuge, a protector and an income. But, characteristically, he wanted more. He was in his forties, his prime, and his ambitions were still inordinate, his conception of his own potential still as extravagant as the awe he inspired. He resolved to make the formidable journey eastward to visit the Great King Artaxerxes at Susa. He would have had in mind the example of Themistocles, the victor of Salamis, another great Athenian who, half a century earlier, had been banished and condemned to death by the city for whom he had won great victories but who had been received with honour by a Persian king. Besides, he had information that Artaxerxes’ brother Cyrus, who was closely associated with the Spartan Lysander, was plotting to usurp the Persian throne. Perhaps he hoped to foment war between Persia and Sparta, a war in which he might play a glorious part as the liberator of Athens.

He asked Pharnabazus to arrange an audience for him with the Great King. Pharnabazus demurred. Alcibiades set out anyway. He halted one night in a small town in Phrygia. There, while he lay in bed with the courtesan Timandra (whose daughter Lais was later said to be the most beautiful woman of her generation), hired killers heaped fuel around the wooden house in which he was lodged and set fire to it. Waking, Alcibiades seized his sword, wrapped a cloak around his left arm for a shield and charged out through the flames. His assassins backed off, but from a distance they hurled javelins and spears at him until he fell. Then they closed in and hacked off his head before departing. Timandra wrapped his decapitated body in her own robe and buried it, or, according to Nepos, burned the dead Alcibiades in the fire that had been set to burn him alive.

Even his death, wretched as it was, is evidence of Alcibiades’ extraordinary charisma. One story goes that the killers were the brothers of a girl he had seduced, but most of the sources agree they had been hired by Pharnabazus. The Satrap had been persuaded to violate the duties of the host, and his affection for the man who had so captivated him, by the urgings of the Spartan Lysander, who had threatened that Sparta would break off its alliance with Persia if Pharnabazus did not hand over Alcibiades, alive or dead. Lysander, in turn, was responding to pressure from Critias – the man who long ago had sat with Alcibiades at Socrates’ feet, and who was now the leader of the puppet government the Spartans had installed in Athens. Such was the potency of Alcibiades’ reputation, so widespread the hope that he might yet come to save his city, that while he lived, complained Critias, ‘none of the arrangements (#litres_trial_promo) he made at Athens would be permanent’. In those dark days for Athens, it was not only the oppressed democrats who ascribed to Alcibiades the power to turn the course of history single-handed. His enemies feared him, or feared the legend he had become. He was a man without a state, without an army, without a fortune, without allies; but he was also a human phoenix who had repeatedly risen from the ashes of disaster in a flaming glory all of his own making.

Alcibiades’ talents were never fully put to the test. His career was a sequence of lost opportunities. Perhaps, given the chance, he might have won the war for Athens. Certainly Thucydides, who was as judicious as he was well informed, believed that the Athenians’ failure to trust Alcibiades (for which Alcibiades, who had failed to win their trust, was partially to blame) brought about the city’s undoing. ‘Although in a public (#litres_trial_promo) capacity his conduct of the war was excellent, his way of life made him objectionable to everyone as a person; thus they entrusted their affairs to other hands, and before long ruined the city.’ But great reputations do not flourish, as Alcibiades’ did in his lifetime and afterwards, on the foundation only of what might have been. It is possible that his career – thwarted, dangerous, and isolated as it was – was precisely suited to his particular genius. He was an actor, a seducer, a legend in his own lifetime and of his own making, a true con-artist, one whose self-invented myth was a creation of awesome grandeur and brilliance, a man who owed the large place he occupied in his contemporaries’ imagination not to any tangible achievement, but simply to the magnitude of his presence.

Poets of the classical and medieval era imagined Achilles to be a giant. He was born different from others. Statius describes him as a baby lapping not milk but ‘the entrails of lions (#litres_trial_promo) and the marrow of half-dead wolves’. Pindar, who lived in Athens a generation before Alcibiades, imagined the six-year-old Achilles outrunning deer, fighting with lions, and dragging the vast corpses of slaughtered boars back to Chiron’s cave. In fiction and myth, exorbitant size and prodigious strength were the tokens of the hero. In the real world, Alcibiades, marked out from others by his aristocratic origins, his striking beauty, his intimidating capacity for violence and his inordinate self-confidence, was received by his contemporaries as though he were another such prodigy, a being intrinsically greater than his fellows.

Such a person is not easily assimilable within any community: in a democracy his very existence is a form of sedition. The dizzying reversals of Alcibiades’ career reflect the constant interplay between his fellow citizens’ adulation of him and their ineradicable distrust of the magic whereby he was able temporarily, but never for long enough, to dominate them. They ascribed to him the potential to be alternately their saviour or their oppressor. They ‘were convinced (#litres_trial_promo)’, wrote Nepos, ‘that it was to him that all their disasters and their successes were due’. They imagined superhuman power for him: they adored him for it, and they found it unforgivable. Like Achilles, he was as terrifying as a god, or a beast. ‘Better not bring up a lion inside your city/But if you must, then humour all his moods’, wrote Aristophanes, with reference to Alcibiades. ‘Most people became frightened (#litres_trial_promo) at a quality in him that was beyond the normal,’ wrote Thucydides. That supranormal quality posed a temptation as alluring as it was insidious. Perhaps what the Athenians feared most in Alcibiades was not any ambition of his to seize absolute power but their own longing to hand it to him, to abase themselves before him as a superman capable not only of rescuing them from their enemies but also of freeing them of the burden of being free.

III CATO (#ulink_42ea4df9-3ef2-59ce-8103-612b62f539d4)

LONDON, 1714. The first night of Joseph Addison’s tragedy, Cato, which was to enjoy such a triumph that Alexander Pope, who wrote the prologue, declared that ‘Cato was not so much (#litres_trial_promo) the wonder of Rome in his days as he is of Britain in ours.’ The curtain rises on the last act. The hero is discovered ‘Solus, sitting in a (#litres_trial_promo) thoughtful posture: in his hand Plato’s book on the Immortality of the Soul. A drawn sword on the table by him.’ The tableau – the sword, the book, the pensive hero – was repeated exactly in numerous neo-classical paintings. Its drama lies not in what is represented, but in what is still to come, the horror to which (as most male members of Addison’s classically educated eighteenth-century audience would have known) this tranquil scene is prelude. Before the night is out Cato will read the book through three times, and then, still serene, still ‘thoughtful’, drive the sword into his belly. When that first attempt to free himself from tyranny fails he will submit calmly while his friends bind up the dreadful wound and remove the weapon. Once more alone, he will tear open his body with his bare hands and resolutely disembowel himself.

Cato, true until death. Cato, so inflexible in his righteousness that he was ready to kill himself not once, but twice. Cato, who had no self-pity, but grieved only for Rome and its venerable institutions. Cato, who, on the night of his death, read of the death of Socrates and who, like the Athenian philosopher, chose not to save himself from a death made inevitable by the mismatch between his own integrity and the imperfection of the world he inhabited. This Cato was venerated alike by pagan Rome and Christian Europe. Addison describes him as ‘godlike’, an epithet first applied to him by Lucan nearly seventeen hundred years earlier. Of his contemporaries, only Julius Caesar, whose most inveterate opponent he was, denied his virtue. Cicero and Brutus both eulogized him. Horace praised his ‘fierce heart (#litres_trial_promo)’. Virgil imagined for him an illustrious afterlife as lawgiver to the virtuous dead. To later generations of Romans, especially to the Stoics who formed the opposition to Nero’s tyranny, he was an exemplar, a philosopher (though he left no philosophical writings), and the embodiment of their ideal. The Christian Fathers saw him as the paragon of pagan virtue. To Lactantius he was ‘the prince of (#litres_trial_promo) Roman wisdom’. To Jerome he had a glory ‘which could neither (#litres_trial_promo) be increased by praise nor diminished by censure’. Dante placed Brutus, who was Cato’s son-in-law and political heir, in the lowest circle of hell with Judas Iscariot, in the very mouth of Satan, to be eaten alive ceaselessly through all eternity, and he condemned others who had, like Cato, committed the sin of self-murder to an afterlife of unremitting mute agony in the form of trees whose twigs ooze blood. But Cato is exempt. Despite being a suicide and a pagan he is the custodian of Dante’s Purgatory and is destined eventually for a place in Paradise. In the Convivio Dante goes even further. Cato divorced his wife Marcia so that she could be married to his political ally Hortensius. After Hortensius’ death he remarried her. The story has proved troubling to most Christian moralists, but Dante treats the couple’s reunion as an allegory of the noble soul’s return to God: ‘And what man (#litres_trial_promo) on earth is more worthy to signify God than Cato? Surely no one.’

It was his intransigence that rendered Cato all but divine. Sophocles, Alcibiades’ contemporary and fellow Athenian, had described the tragic hero as one who refuses to compromise or conform but remains, however beset by trouble, as immovable as a rock (#litres_trial_promo) pounded by stormy seas, or as the one tree which, when all the others preserve themselves by bending before a river in flood, stays rigidly upright and is therefore destroyed root and branch. Cato was as steadfast as that rock, as self-destructively stubborn as that tree. An Achilles, not an Odysseus, he was the antithesis of Alcibiades, the infinitely adaptable, infinitely persuasive charmer. Cato never charmed, never changed.

He has been revered as a hero, but he put all his energies into thwarting the aspirations of the heroic great men among his contemporaries, and into attempting to save his fellow Romans from the folly of the hero-worship he so passionately denounced. The defining drama of his life was his resolute opposition to Julius Caesar. Friedrich Nietzsche considered Caesar to be one of the few people in human history to have rivalled Alcibiades’ particular claims to superman status, the two of them being Nietzsche’s prime examples of ‘those marvellously incomprehensible (#litres_trial_promo) and unfathomable men, those enigmatic men predestined for victory and the seduction of others’. Cato was their opposite. Obstinately tenacious of a lost cause, he was predestined for defeat and temperamentally incapable of seduction.

Caesar – adroit and charismatic politician, ruthless, brilliant conqueror – was a hero of an instantly recognizable type. Cato’s claim to heroic status is of quite a different nature. He is the willing sacrifice, the patiently enduring victim. His glory is not that of the brilliant winner but of the loser doggedly pursuing a course that leads inevitably to his own downfall. Small wonder that Christian theologians found his character so admirable, his story so inspiring. He embodied the values of asceticism and self-denial that Jesus Christ and his followers borrowed from pagan philosophers and, like Christ’s, his life can be seen with hindsight as a steady progress towards a martyr’s death.

That death retrospectively invested his career and character with a melancholy grandeur that compensated for the glamour which, alive, he notably lacked. Curmudgeonly in manner, awkward and disobliging in his political dealings and his private relationships alike, he sought neither his contemporaries’ affection nor posterity’s admiration. Yet he received both. Cicero, who knew him well, wrote that he ‘alone outweighs (#litres_trial_promo) a hundred thousand in my eyes’. ‘I crawl (#litres_trial_promo) in earthly slime,’ wrote Michel de Montaigne, some sixteen hundred years after Cato’s death, ‘but I do not fail to note way up in the clouds the matchless heights of certain heroic souls’, the loftiest of them all being Cato, ‘that great man who was truly a model which Nature chose to show how far human virtue and fortitude can reach’.

He had a personality of tremendous force. His contemporaries were awed and intimidated by him – not as the Athenians had feared the capricious bully Alcibiades, more nearly as the moneylenders in the Temple feared the righteous and indignant Christ. His mind was precise and vigorous and he was an orator of furious talent. He was deferred to, by the soldiers he commanded, by the crowds he stirred or subdued, by those of his peers who recognized and admired his selflessness and integrity; but he was also a troublemaker and an oddity. He was a well-known figure in Rome, but one who inspired irritation and ridicule as well as respect.

He was a nuisance. He embarrassed and annoyed his peers by loudly denouncing corrupt practices that everyone else had come to accept as normal. He had no discretion, no urbanity. He looked peculiar. He habitually appeared in the Forum with bare feet and wearing no tunic beneath his toga, an outfit that seemed to his contemporaries at best indecorous, at worst indecent. When challenged about it he pointed to the statue of Romulus (represented similarly underdressed) and said that what was good enough for the founder of Rome was good enough for him. When he became praetor (a senior magistrate) his judgements were acknowledged to be scrupulously correct; but there were those who muttered that he disgraced the office by hearing cases – even those solemn ones in which important men stood to incur the death penalty – looking so raffish, so uncouth.

He never laughed, seldom smiled and had no small talk. He stayed up late, all night sometimes, drinking heavily; but his nightlife was not of the gracious and hospitable kind that his fellow aristocrats found congenial. Rather, he would engage in vehement debate with philosophers who tended to encourage him in his eccentricities. Rigorously ascetic, he disdained to think of his own comfort, and had a way of undermining other people’s. He never rode if he could walk. When he travelled with friends he would stalk along beside their horses on his bare and callused feet, his head uncovered, talking indefatigably in the harsh, powerful voice that was his most effective political weapon. Few people felt easy in his company; he was too judgemental and too much inclined to speak his mind. To his posthumous admirers his disturbing ability to search out others’ imperfections was among his godlike attributes. Montaigne called him one ‘in whose sight (#litres_trial_promo) the very madmen would hide their faults’. But his contemporaries shunned him for it. He was his community’s self-appointed conscience, and the voice of conscience is one to which most people prefer not to listen. His incorruptibility dismayed his rivals: ‘the more clearly (#litres_trial_promo) they saw the rectitude of his practice’, writes Plutarch, ‘the more distressed were they at the difficulty of imitating it’. All the great men of Rome ‘were hostile to Cato (#litres_trial_promo), feeling that they were put to shame by him’. Even great Pompey was said to have been unnerved by him. ‘Pompey admired him (#litres_trial_promo) when he was present but … as if he must render account of his command while Cato was there, he was glad to send him away.’

His life (95–46 BC) coincided with the last half century of the Roman Republic, a time of chronic political instability and convulsive change. It was a time when the institutions of the state had ceased to reflect the real distribution of power within it. Rome and all its provinces were nominally ruled by the Senate and the people of Rome; but by the end of Cato’s life, Rome’s dominions extended from the Euphrates to the Atlantic, from the Sahara to the North Sea. The constitution, evolved within a city-state, provided none of the machinery required to subdue, police, and administer an international empire. The prosecution of foreign wars and the exploitation of the conquered provinces required great armies and teams of officials – none of which Rome’s institutions could provide. The provinces were effectively autonomous states, far larger and frequently richer than the metropolis, with their own separate administrations. The pro-consuls who conquered and governed them at their own expense and to their own profit, who were often absent from Rome for years on end acting as effectively independent rulers in their allotted territories, and who returned at last enormously wealthy and to the adulation of the people, had, in reality, infinitely more clout than the institutions they were supposed to serve. When Pompey celebrated his triumph on returning from Asia in 61 BC his chariot was preceded by the captive families of three conquered kings. He boasted of having killed or subjected over twelve million people and of increasing Rome’s public revenues by 70 per cent. There was no room in the Republic for such a man, no legitimate channel for his influence or proper way in which he could exert his power. The Athenians had been afraid when Alcibiades demonstrated his prowess, his wealth, and his international connections at Olympia. Just so were the Roman republicans apprehensive as first Pompey, and subsequently Crassus and Caesar, grew so great they loomed over the state like unstable colossi.

Cato was the little man who dared oppose these giants, the Prometheus nobly defying the ruthless gods (one of whom Caesar would soon become) for the sake of oppressed humanity. Armed only with his voice, his knowledge of the law and his unshakeable certainty of his own rectitude, he resolutely obstructed their every attempt to have their actual power acknowledged. Whether he was wise to do so is open to question. Theodor Mommsen, the great nineteenth-century German historian, called Cato an ‘unbending dogmatical fool’ (#litres_trial_promo). Even Cicero, who thought so highly of him and whose political ally he was throughout most of their contemporaneous careers, found him exasperating at times. Cicero was a pragmatist, a sophisticated political operator and a practitioner of the art of the possible. Cato, by contrast, loudly and dogmatically insisting on the letter of ancient and anachronistic laws, repeatedly damaged his own cause by exposing his allies’ misdemeanours and defending his opponents’ rights. To many commentators, ancient and modern alike, it has appeared that, had it not been for Cato’s dogged refusal to compromise his political principles, or to allow anyone else to do so without being publicly shamed, the Senate might have been able to come to terms with Julius Caesar in 49 BC, that Caesar need never have led his troops across the Rubicon, that thousands of lives might have been saved.

But Cato’s failings are identical with his claims to heroic status. What in the man was awkward was transmuted by time and changing political circumstance to become, in the context of the legend that grew up around him, evidence of his superhuman fortitude. His obstinate refusal to take note of historical change or political expediency are manifestations of his magnificent staunchness. His tactlessness and naivety are the tokens of his integrity. His unpopularity proves his resolution. Even his downfall is a measure of his selfless nobility. He opposes Julius Caesar – by common consent one of Western history’s great men – and is inevitably defeated by him; but his defeat makes him even greater than that great opponent. He dies as a flawed and vulnerable person, and rises again as a marmoreal ideal. Seneca, writing in the next century, imagined the king of the gods coming down among men in search of instances of human grandeur. ‘I do not know (#litres_trial_promo) what nobler sight Jupiter could find on earth,’ he wrote, ‘than the spectacle of Cato … standing erect amid the ruins of the commonwealth.’

His life began and ended in times of civil war. When he was seven years old the Roman general Sulla marched on Rome at the head of his legions, demanding the leadership of the campaign against King Mithridates of Pontus. The Senate capitulated. Sulla then departed for the East, leaving his followers to be killed by his political enemies. Five years later, after having subdued all Asia Minor, he returned to Italy and fought his way to Rome, confronting and defeating the armies of the consuls. Once he had taken the city, the people granted him absolute power. He set about putting to death anyone who had opposed him. His proscriptions, the terrible lists of those outlawed with a price on their heads that served as an incitement to mass murder, were posted in the Forum. Forty senators and at least sixteen hundred others (nine thousand (#litres_trial_promo) according to one source) were named. Some were formally executed, some murdered by Sulla’s paid killers, some torn apart by the mob. Cato was thirteen at the time. His father, by then dead, had been favoured by Sulla. Plutarch, who wrote his Life of Cato a century and a half after the latter’s death but whose sources included accounts (subsequently lost) written by Cato’s contemporaries, relates that the boy’s tutor took him to pay court to the dictator. Sulla’s house was an ‘Inferno’, where his opponents were tortured, and on whose walls their severed heads were displayed. Early in his life Cato witnessed at first hand what befalls a state whose constitution has been overturned by a military dictator.

He bore an illustrious name. He was the great-grandson of Cato the Censor, a man who was remembered as an embodiment of the stern virtues that those who came later liked to imagine had been characteristic of the Roman Republic in its prime. The Censor was a byword for his asceticism and his moral rigour. He travelled everywhere on foot, even when he came to hold high office. At home he worked alongside his farm labourers, bare-chested in summer and in winter wearing only a sleeveless smock, and was content with a cold breakfast, a frugal dinner and a humble cottage to live in. Wastage was abhorrent to him. To his rigorous avoidance of it he sacrificed both beauty and kindness. He disliked gardens: land was for tilling and grazing. When his slaves became too old to work, he sold them rather than feed useless mouths. In office he was as harsh on others as he was on himself. When he discovered that one of his subordinates had been buying prisoners of war as slaves (a form of insider dealing that was improper but not illegal) the man hanged himself rather than suffer the Censor’s rebuke. Grim, graceless and incorruptible, the elder Cato was unpopular but generally revered. The younger Cato, or so several of his contemporaries believed, took him as a model.

His early career followed the conventional path for a young man of Rome’s ruling class. When Crassus put down the revolt of the slaves under Spartacus Cato served as a volunteer in his army, his zeal and self-discipline, according to Plutarch, providing a striking contrast with the ‘effeminacy and luxury (#litres_trial_promo)’ of his fellow officers. Like his virtuous ancestor, who ‘never embraced (#litres_trial_promo) his wife except when a loud peal of thunder occurred’, he was sexually abstemious, remaining a virgin until his first marriage (something unusual enough to arouse comment). Surly and forbidding in company, in private he drilled himself rigorously for the political career before him. He frequented philosophers, especially the Stoic Antipater, ‘and devoted himself (#litres_trial_promo) especially to ethical and political doctrines’. He trained his voice and disciplined his body not only by exercising hard but also by a programme of self-mortification involving exposure to all weathers.

When he was twenty-eight he stood for election as one of the twenty-four military tribunes chosen each year. In canvassing for support he shamed and irritated his fellow candidates by being the only one of them to obey the law forbidding the employment of nomenclatores, useful people (usually slaves) whose job it was to murmur in the candidate’s ear the name of the man whose vote he was soliciting. Despite this self-imposed handicap he won his place and was posted to Macedonia to command a legion. He proved himself an efficient and popular officer. When his year’s term of office was up he made a grand tour of Asia Minor before returning home, stopping at Ephesus to pay his respects to Pompey. To the surprise of all observers, Rome’s greatest commander (Caesar’s career was only just beginning) rose to greet the young man, advanced towards him and gave him his hand ‘as though to honour (#litres_trial_promo) a superior’.

Cato was still young, his political career had yet to begin, but he was already somebody to whom the mighty deferred. Quite how he achieved that status is mysterious. He was not physically remarkable: none of the ancient authors considered his looks worth describing. A portrait bust shows him with a lean and bony face, a serviceable container for a mind but not a thing of beauty. He came of a distinguished family, but so did plenty of other hopeful young Romans. He had inherited some money: so did most men of his class. He had done decent service in the army, but he was never to prove a particularly gifted warrior. His distinguishing characteristics were those of inflexibility and outspokenness, scarcely the best qualifications for worldly success. He was more studious than most, but what was impressive about him seems to have had little to do with his intellectual attainments. Something marked him out, something very different from the dangerous brilliance of Achilles or Alcibiades’ winning glamour, something his contemporaries called ‘authority’.

According to Plutarch, he had already been a known and respected figure in his early teens. When Sulla was appointing leaders for the two teams of boys who performed the ritual mock battle, the Troy Game, one team rejected the youth appointed and clamoured for Cato. In adulthood his nature, wrote Plutarch, was ‘inflexible, imperturbable (#litres_trial_promo), and altogether steadfast’. His peers were awed by it. His acknowledged incorruptibility gave him a kind of power that was independent of any formal rank. From his first entry into public life the amount of influence he was able to exert and the deference he inspired were unprecedented for one so comparatively young. His ascendancy over the Roman political scene has been described by the German historian Christian Meier as ‘one of the strangest (#litres_trial_promo) phenomena in the whole of history’. Inexplicable in terms of his official or social status, it can only have derived from the extraordinary force of his personality.

By the time he returned to Rome from Asia he was thirty, and therefore eligible to stand for election as one of the twenty quaestors chosen annually. The constitution of Republican Rome was a complicated hybrid, evolved over centuries. The Greek historian Polybius, who had been held hostage in Rome in the previous century, had described it as being at once monarchy, oligarchy, and democracy. His analysis is not exact – no one within the Republic had the absolute lifelong power of a monarch – but near enough. The consuls, of whom two at a time were elected for a year’s term, seemed to Polybius like kings. Originally the consuls had been military commanders and generally absent from the metropolis, but by Cato’s day it had become normal for them to remain in Rome for their year of office, departing at the end of it each to his own province (traditionally chosen by lot), which he would govern for a further year.

The consuls were the senior members of the Senate, but they were not prime ministers. The state was administered by annually elected officials – in ascending order of seniority, quaestors, aediles, praetors and consuls – each of whom held power independently of all the rest. There might be alliances between officeholders, but there was no unified government, no cabinet of ministers working in concert. Anyone who had ever held office became a lifelong member of the Senate. Theoretically, any free adult male could present himself for election to office once he attained the prescribed age. In practice, only the rich could afford to do so. Election campaigns were expensive; bribery was commonplace; and if it cost a lot of money to gain office, it cost far more to hold it. Officials were expected to provide their own staff, to lay on public games and maintain public buildings, all at their own expense. And not only were officeholders obliged to spend money copiously: they were debarred, for the rest of their lives, from earning it. It was forbidden for a senator to engage in business. Besides, to win elections it was necessary to have the right connections. Inevitably, the majority of officeholders and senators were drawn from a small pool of families, of which Cato’s was one, of substantial wealth and long-established influence.

Rome was nonetheless a democracy. The Senate was not a legislative body, its members could propose laws, but those laws were passed or rejected by the people of Rome (that is, the male, adult, unenslaved people) voting in person. And the people’s interests were protected by the tribunes of the people, elected officials (ten a year) who shared with the consuls and praetors the right to propose laws to the voters, who had the devastating power of the veto – a single tribune could block any measure – and whose persons were sacrosanct.

In Cato’s lifetime this ramshackle and mutually inconvenient assemblage of institutions began to fall apart. The upholders of the ancient constitution – of whom Cato was to become the most passionately committed – struggled to enforce the elaborate rules that were designed, above all, to ensure that no one man should ever achieve too much power. They failed. Defying the Senate, making use of the tribunes and appealing direct to the people, first Pompey, then Crassus, and finally Julius Caesar demanded and obtained powers that vastly exceeded any that the constitution allowed. It was Cato’s life’s work to oppose them.

From his first entry into public life Cato signalled his punctilious regard for the workings of the constitution. To most candidates the post of quaestor, the most junior magistracy, was primarily the portal through which a man entered the Senate – not so much a job as a rite of passage. In 65 BC Cato astonished all observers by qualifying himself for the position before applying for it. The quaestors were responsible for the administration of public funds. According to Plutarch, Cato ‘read the law (#litres_trial_promo) relating to the quaestorships, learned all the details of the office from those who had had experience in it, and formed a general idea of its power and scope’. Once elected he assumed control of the treasury, instituting a purge of the clerks who had been accepting bribes and embezzling money with impunity. Next he set about paying those, however insignificant, to whom the state was indebted, and ‘rigorously and inexorably’ demanding payment from those, however influential, who were its debtors – a policy whose simple rectitude appeared to his contemporaries breathtakingly novel.

The society in which Cato lived was described by his contemporary Sallust (who was himself convicted of extortion) as one in which ‘instead of modesty (#litres_trial_promo), incorruptibility and honesty, shamelessness, bribery and rapacity held sway’. Sulla’s coup, the ensuing civil wars and his reign of terror had left the state punch-drunk and reeling. More recently and insidiously, a series of constitutional reforms and counter-reforms had undermined the perceived legitimacy of established institutions. Meanwhile wealth flooded into Rome from the conquered provinces, but there was no mechanism whereby the state could put it to good use and few channels for its redistribution among the populace. Rome had no revenue service. Romans paid no tax, but the inhabitants of the overseas provinces did. The money was collected by tax farmers, who paid dearly for the right to do the job and who set the level of tribute exacted high enough to ensure themselves handsome profits. The Roman provincial governors who oversaw their operations took their cut as well. Corruption was endemic throughout the system. The records of Rome’s law courts are full of cases of returning governors facing charges of extortion. It was a time when the best lacked all conviction: Sallust denounced those magnates who squandered their wealth shamefully on fantastically grandiose projects for beautifying their private grounds – ‘they levelled mountains (#litres_trial_promo) and built upon the seas’ – instead of spending it honourably for the public’s good, and Cicero inveighed against aristocrats who chose to retire to their country estates and breed rare goldfish rather than wrestle with the intractable problems besetting the state.

In such a society Cato, scrupulously balancing his books, shone out. Heroes of a flashier sort disdain accountancy. In Alcibiades’ youth, when his guardian Pericles was accused of using public money for his own private ends, Alcibiades told him ‘You should be seeking (#litres_trial_promo) not how to render, but how not to render an accounting’ and advised him to divert attention from his alleged embezzlements by provoking a major war. But Cato was a man who believed that right and wrong were absolute and non-negotiable, that ethics was a discipline as clear and exact as arithmetic. In paintings of his death it is conventional for the artist to include, along with the sword and the book, an abacus, the tool of the accountant and token of his absolute integrity.

Under Cato’s administration the treasury became an instrument of justice. There were still at large several men known to have been used as assassins by Sulla at the time of his murderous proscriptions. ‘All men hated them (#litres_trial_promo) as accursed and polluted wretches,’ says Plutarch, ‘but no one had the courage to punish them.’ No one, that is, except Cato. He demanded that they repay the large sums with which they had been rewarded for their killings, and publicly denounced them. Shortly thereafter they finally came to trial.

Cato possessed, writes Plutarch, ‘that form of goodness (#litres_trial_promo) which consists in rigid justice that will not bend to clemency or favour’. Eccentric as his straight dealing was perceived to be, it won him a degree of respect quite disproportionate to his actual achievements. His truth-telling became a by-word. ‘When speaking of matters that were strange and incredible, people would say, as though using a proverb “This is not (#litres_trial_promo) to be believed even though Cato says it”.’ Any defendant who attempted to have him removed from a jury was immediately assumed to be guilty. His evident probity gave him a degree of power out of all proportion to his official rank. It was said that he had given the relatively lowly office of quaestor the dignity normally attached to that of consul.

He had become a notable player in the political game. That game, as played in the last years of the Roman Republic, was a rough one. Rome had no police force. Prominent people never went out alone. In good times they were accompanied wherever they went by an entourage of clients and servants. In bad times they had their own trains of guards-cum-enforcers, troops of armed slaves and gladiators, in some cases so numerous as to amount to private armies. Political dispute developed, rapidly and often, into physical conflict. To read the ancient historians’ account of the period is to be repeatedly astonished by the contrast between the grandeur and efficacy of Rome’s rule over its expanding empire and the rowdiness and violence at its very heart. The Forum was not only parliament, law court, sports arena, theatre and place of worship. It was also, frequently, a battlefield. The temples that surrounded it, which were used on occasion as debating chambers or polling stations, could and frequently did serve as fortresses occupied and defended by fighting men. During his career Cato was to be spat upon, stripped of his toga, pelted with dung, dragged from the rostrum (the platform in the Forum from which orators addressed the people), beaten up and hauled off to prison. He escaped with his life, but he was present on occasions when others did not. The making of a political speech, in his lifetime, was an act that called for considerable courage.

His quaestorship over, he was an assiduous senator, always the first to arrive in the morning at the Senate House and the last to leave, attending every session to ensure no corrupt measure could be debated without his being there to oppose it. But in 65 BC he resolved to take a reading holiday. He set off for his country estate, accompanied by a group of his favourite philosophers and several asses loaded down with books. The projected idyll – quiet reading and high-minded discussion in a bucolic setting – was aborted. On the road Cato met Metellus Nepos, brother-in-law and loyal supporter of Pompey. Learning that Nepos was on his way to Rome to stand for election as a tribune of the people, Cato decided that it was his duty to return forthwith and oppose him.

It was an edgy time in Rome. Two years previously, during Cato’s quaestorship, a group of influential men had plotted a coup d’état. The plot was aborted, but those suspected of instigating it were all still at liberty, all highly visible on the political scene. The ancient historians differ as to who they were. Sallust identifies the ringleader as Catiline, a charismatic, dangerous man whom Cicero credited with a phenomenal gift for corrupting others and a corresponding one for ‘stimulating his associates (#litres_trial_promo) into vigorous activity’. Catiline was a glamorous figure: nineteen hundred years later Charles Baudelaire was to identify him, along with Alcibiades and Julius Caesar, as being one of the first and most brilliant of the dandies. Scandals clung to his name. He was said to have seduced a vestal virgin, even to have murdered his own stepson to please a mistress. His sulphurous reputation had not prevented him achieving the rank of praetor, but his first attempt to win the consulship was thwarted when he was accused of extortion. Sallust maintains that, prevented from attaining power by legitimate means, Catiline plotted to assassinate the successful candidates and make himself consul by force. Suetonius, on the other hand, asserts that the chief conspirators were Crassus and Caesar.

Crassus was a man some seventeen years older than Cato who had grown fabulously rich by profiting from others’ misfortunes. He had laid the foundations of his wealth at the time of Sulla’s proscriptions, buying up the confiscated property of murdered men at rock-bottom prices. He had multiplied it by acquiring burnt-out houses for next to nothing (in Rome, a cramped and largely wooden city, fires were frequent and widespread) and rebuilding them with his workforce of hundreds of specially trained slaves until he was said to own most of Rome. A genial host, a generous dispenser of loans and a shrewd patron of the potentially useful, he ensured that his money bought him immense influence. No one, he is reported to have said, could call himself rich until he was able to support an army on his income. He was one who could.

Julius Caesar was one of Crassus’ many debtors. Five years older than Cato and politically and temperamentally his opposite, he was already noted for his military successes, his sexual promiscuity and his fabulous munificence – all of which endeared him to the populace. As aedile in 65 BC, the year of the alleged conspiracy, he staged at his own expense a series of wild-beast hunts and games of unprecedented magnificence, filling the Forum with temporary colonnades and covering the Capitoline Hill with sideshows. In Alcibiades’ lifetime, Plato had warned ‘any politician who seeks (#litres_trial_promo) to please the people excessively … is doing so only in order to establish himself as a tyrant’. Whether or not he was actually plotting sedition, Caesar was already one of the handful of men who threatened to destabilize the Roman state – as Alcibiades had once undermined the stability of Athens – simply by being too glittering, too popular, too great.

But though Catiline, Crassus and Caesar were all present in Rome when Cato returned in 63 BC to stand for election, it was Pompey whom the guardians of republican principles were watching most apprehensively. It was because Metellus Nepos was Pompey’s man that Cato had felt it so imperative to oppose him. Pompey had treated Cato graciously in Ephesus, but Cato was not the man to be won over by a display of good manners, however flattering. Cato was a legalist. His political philosophy was based on the premise that only by a strict and absolute adherence to the letter of the law could the Republic be preserved. Pompey’s entire career had been conducted in the law’s defiance.

When only twenty-three he had raised an army of his own and appointed himself its commander. When he returned triumphant from Spain in 71 BC he had insisted on being allowed to stand for consul – the highest office in the state – despite the fact that he was ten years too young and had held no previous elected office, and he had backed up his demand by bringing his legions menacingly close to the city. Sulla had drastically reduced the powers of the tribunes and enhanced those of the Senate. As consul in 70 BC, Pompey had reversed the balance. In subsequent years he had seen to it that a fair number of the tribunes were his supporters and he worked through them, as Caesar was to do later, to bypass the increasingly unhappy Senate and appeal directly to the electorate for consent to the expansion of his privileges and power.

In 66 BC a tribune had proposed and seen through a law granting Pompey extraordinary and unprecedented powers to rid the eastern Mediterranean of pirates. In the following year another tribune had proposed that he should be granted command of the campaign against Mithridates of Pontus (Sulla’s old adversary who had risen against Rome again). Military commands brought glory, which in turn brought popularity. They brought tribute money and ransoms and loot that could be used to buy power. Military commanders also had armies (which the Senate did not). Pompey had been spectacularly successful, both against the pirates and against Mithridates. There were plenty who remembered that he had begun his career as one of Sulla’s commanders, that it was Sulla who had named him ‘Pompey the Great’. And Sulla, who had returned from defeating Mithridates to make war on Rome itself, had set a terrible precedent. In 63 BC the senators awaited the return of their victorious general with mounting fear.