По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

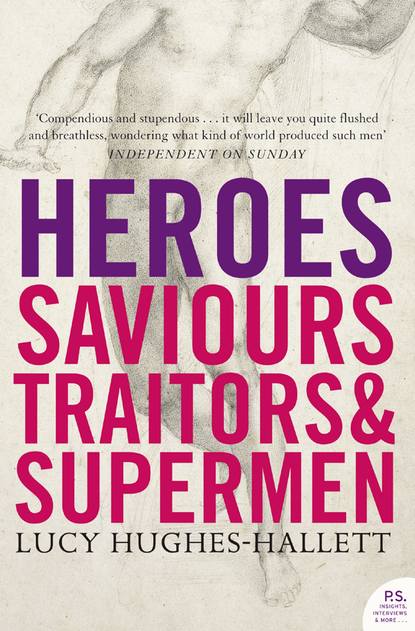

Heroes: Saviours, Traitors and Supermen

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

When the war is over, when the fabled towers of Troy are shattered, its riches plundered and its people slaughtered or enslaved, when the Greeks at last have sailed away, Poseidon and Apollo throw down the massive rampart that protected the Greek ships. The proper sacrifices were not made before building began. The prodigious wall is an impious defacement of the landscape. The gods call upon the waters of the earth to wash it away. Rivers in flood, torrential rain, the sea’s breakers, all batter against it until there is nothing left of that desperate labour. Poseidon ‘made all smooth (#litres_trial_promo) along the rip of the Hellespont/And piled the endless beaches deep in sand again’. This war, the most celebrated in human history, is to leave no trace upon the face of the earth.

‘You’d think me (#litres_trial_promo) hardly sane,’ says Apollo to a fellow god, ‘if I fought with you for the sake of wretched mortals./Like leaves, no sooner flourishing, full of the sun’s fire,/Feeding on earth’s gifts, then they waste away and die.’ Human affairs, viewed sub specie aeternitatis, are of gnat-like insignificance. Human aspirations are absurd, and human lifespan as short as summer’s lease.

For Homer’s heroes there is no sublime afterlife to compensate for this one’s brevity. The souls of the dead survive, but once parted from their bodies their existence is shadowy and mournful. When a warrior dies his soul goes ‘winging down (#litres_trial_promo) to the House of Death,/ Wailing its fate, leaving his manhood far behind,/His young and supple strength’. Physical beauty, the marvellous vigour and grace of the human body, these are life’s splendours. The pleasures of the intellect, of stratagem and story telling and debate, are prized as well, but they too are a part of corporeal life, dependent for their very existence on ear and tongue and brain. ‘In Death’s strong house (#litres_trial_promo),’ says Achilles, ‘there is something left/A ghost, a phantom – true, but not real breath of life.’

Achilles and his fellows treat bodies, alive or dead, with reverence and tenderness – or with a violence that deliberately outrages the body’s acknowledged sanctity. More than half of the fighting described in the Iliad consists of battles over corpses, as a warrior’s enemies try to strip his fallen body of armour (which, poignantly, is far more durable than its wearers) while his comrades struggle to defend him from such posthumous indignity, giving their lives sometimes to save one already dead. It is the flesh that is precious: without it, the spirit is of little consequence. Funerals are awesome, long-drawn-out, and prodigally expensive. Funeral games honour the dead by celebrating the survivors’ bodily strength and swiftness and skill, insisting, even in commemoration of one who has lost it, that the breath of life is of ineffable value. And once gone it is irretrievable. Achilles refuses all Agamemnon’s proffered presents, and he would refuse them even if they were as numberless as the sand; for all the world’s wealth is worth less than his little time in the sun. ‘A man’s life’s breath (#litres_trial_promo) cannot come back again once it slips through a man’s clenched teeth.’

But just as the discarnate spirit is a sad and paltry thing, so the inanimate flesh is gross and open to the most squalid abuse. The dignity of embodied man is exquisitely precarious. ‘Oh my captains (#litres_trial_promo),’ cries Patroclus, grieving over the beleaguered Greeks. ‘How doomed you are … to glut with your shining fat/The wild dogs of battle here in Troy.’ The Homeric warriors, who have lived for over nine years by a battlefield, the horrors of war perpetually before their eyes, are haunted by the knowledge that the strong arms, the tireless shoulders, the springy knees in which they take such pride, are also so much grease to be melted and swallowed up by the impartial earth, so many joints of meat. In one of this harsh poem’s most desolating passages King Priam foresees his own death. ‘The dogs before my doors (#litres_trial_promo)/Will eat me raw … The very dogs/I bred in my own halls to share my table … mad, rabid at heart they’ll lap their master’s blood.’ Death cancels all relationship, annuls all status. ‘The dogs go at the grey head and the grey beard/And mutilate the genitals.’ Even a king like Priam, his life’s breath gone, is reduced to unlovely matter, defenceless, disgusting. When Zeus sees Achilles’ immortal horses weeping for Patroclus he apologizes to them for having sent them to live with mortals, whose inevitable destiny is so pitiful, so degrading. ‘There is nothing (#litres_trial_promo) alive more agonized than man.’

There is one way to salvage something from the brutal fact of death. To the Homeric warriors it seemed that the fearless confrontation of violence with more violence might be a way to transform themselves from destructible things into indestructible memories. A man without courage is mere evanescent matter. ‘You can all turn (#litres_trial_promo) to earth and water – rot away,’ Menelaus tells the Greeks when none among them is brave enough to take up Hector’s challenge to single combat. But a man ready to go out and meet death cheats it. It is on the battlefield, as Homer tells us over and over again, ‘that men win glory’, and for the ancients the winning of glory had a precise and urgent purpose. ‘Ah my friend (#litres_trial_promo),’ says Sarpedon to his comrade, ‘if you and I could escape this fray and live forever, never a trace of age, immortal,/I would never fight on the front lines again/Or command you to the field where men win fame./But now as it is, the fates of death await us/ … and not a man alive/Can flee them or escape – so in we go for the attack!/Give our enemy glory or win it for ourselves.’ Only glory could palliate the grim inexorability of death. The man who attained it distinguished himself in life from the mass of his fellows, and when he died he escaped oblivion.

Achilles’ surpassing beauty is precious not because of any erotic advantage it may give him but because, along with his strength and prowess, it renders him outstanding. His celebrity is profoundly important to him, as it would be to any of his peers. It is not frivolous vanity that makes him prize it so. A man who is praised and honoured while he is alive may be remembered even after his body is reduced to ashes and his spirit has gone down into the dark. To be forgotten is to die utterly. To Agamemnon, facing defeat as the Trojans close on the Greek ships, the most terrible aspect of the fate awaiting him and his army is that, once they have been massacred so far from home, their memory will be ‘blotted out’. The only moment in the Iliad when Achilles shows fear is when the River Xanthus comes close to overpowering him, to sweeping him away ignominiously ‘like some boy (#litres_trial_promo), some pig-boy’ and threatens to bury him in slime and silt so deep that his bones will never be found, and no fine burial mound will ensure his lasting fame.

‘Remember (#litres_trial_promo),’ says the mysterious wise woman Diotima to Socrates in Plato’s Symposium, ‘that the love of fame and the desire to win a glory that shall never die have the strangest effects on people. For this even more than for their children they are ready to run risks, spend their substance, endure every kind of hardship and sacrifice their lives.’ Achilles, she goes on, would surely not have given his life had he not believed that his ‘courage would live for ever in men’s memory’. Pindar, writing a generation before Plato, rejoiced that in the hero’s lifetime ‘the voice of poets (#litres_trial_promo) made known … the new excellence of Achilles’, that in his death ‘song did not abandon him’, that the Muses themselves chanted dirges around his pyre, and that the gods ordained that he, or rather his memory, should be tended and sustained by them for ever more.

St Augustine understood the ancients’ craving for fame, and what seemed to him their over-valuation of the ‘windy praise (#litres_trial_promo) of men’. Looking back from the standpoint of one to whom Christ’s death had offered the hope of heaven, he wrote forgivingly of the folly with which they tried to extend and to give significance to their pathetically finite lives. ‘Since there was no eternal life for them what else were they to love apart from glory, whereby they chose to find even after death a sort of life on the lips of those who sang their praise?’

That windy afterlife could be attained by killing. Hector, challenging Ajax to single combat, promises to return his victim’s body, should he kill him, so that the Greeks can build a burial mound: ‘And some day (#litres_trial_promo) one will say, one of the men to come,/Steering his oar-swept ship across the wine-dark sea,/“There’s the mound of a man who died in the old days,/One of the brave whom glorious Hector killed”. So they will say, some day, and my fame will never die.’ Better still, it could be achieved by being killed in battle. In the Odyssey Achilles’ shade and that of Agamemnon meet in the Underworld. Agamemnon who, alive, insisted so vehemently on his supremacy, now defers to the other, paying tribute to Achilles’ glorious end. Rank confers honour, but only a soldier’s death brings glory. Murdered on his return to Mycenae by his wife Clytemnestra, Agamemnon, as the victim of a squalid and abhorrent crime, is degraded in perpetuity. He wishes, and Achilles agrees that he is right to do so, that he had been killed at Troy. Enviously, he describes Achilles’ funeral, the eighteen days of unbroken mourning and sombre ceremony, the tears, the dirges, the burnt offerings, the games, the long cortège of men in battle armour, the resounding roar that went up when the pyre was lit, the great tomb built over the hero’s bones. ‘Even in death (#litres_trial_promo) your name will never die … /Great glory is yours, Achilles,/For all time, in the eyes of all mankind.’

The gods held to their side of the bargain Achilles made. His fame has yet to die. For the Greeks of the classical era, for the Romans after them, and – after a lapse of nearly a thousand years during which the Greek language was all but forgotten in the West – for every educated European gentleman (and a few ladies) from the Renaissance until the beginning of the twentieth century, the two Homeric epics were the acknowledged foundations of Western culture, and ‘the best of the Achaeans’ the prototypical hero. Even now, as this book goes to press, a new film version of the Troy story is being advertised, one in which Brad Pitt, described as Hollywood’s handsomest actor, plays Achilles. It is a role many illustrious men have coveted.

In 334 BC Alexander, the 22-year-old King of Macedonia, already remarkable for his daring and his vast ambition, chose to make his first landfall in Asia on the beach traditionally held to be the one where, some nine centuries earlier, the Greeks’ black ships were drawn up throughout the ten harrowing years that they laid siege to Troy. Alexander slept every night with a copy of the Iliad, which he called his ‘journey-book (#litres_trial_promo) of excellence in war’, beneath his pillow along with a dagger. He claimed that his mother was descended from Achilles. He encouraged his courtiers to address him by Achilles’ name. As his fleet neared the shore he dressed himself in full armour and took the helm of the royal trireme. Before embarking on his world-subduing campaign, Alexander had come to pay tribute to his model.

At Troy, at this period a mere village, he refused the citizens’ offer of the instrument on which Paris (also known as Alexander) used to serenade Helen. ‘For that lyre (#litres_trial_promo),’ he told them, ‘I care little. I have come for the lyre of Achilles, with which, as Homer says, he would sing of the prowess and glories of brave men.’ As Achilles had sung to himself in his tent, evoking the reputation of the heroes dead and gone among whom he wished to be numbered, so Alexander, at this momentous starting-point, solemnly honoured his great forerunner. Stripped naked, and anointed with oil, he ran with his companions to lay a garland on Achilles’ tomb.

That a young Hellenic king ambitious of military conquest in Asia and intent on creating for himself the reputation of a warrior to compare with those of the legendary past should choose Achilles as model and patron is perhaps predictable. But a generation earlier a great man of a very different stamp had also invoked his name. In 399 BC the 70-year-old philosopher Socrates was put on trial in Athens, accused of refusing to recognize the city’s gods, of introducing new deities, and of corrupting the young. He was summoned before a court consisting of five hundred of his peers and invited to make his defence. He proceeded, not to answer the charges against him, but to make a mock both of them and of his chief accusers. Then, midway through his defence (as it was written down by Plato some years after the event), his tone altered. For a while, his famous irony and his provocative sangfroid alike were laid aside. He was unpopular, he said, he realized that, and he had known for some time that he risked incurring a capital charge. But to one who might ask him why, in that case, he persisted in a course that was so evidently irritating to the authorities he said that he would answer: ‘You are mistaken (#litres_trial_promo), my friend, if you think that a man who is worth anything ought to spend his time weighing up the prospects of life and death. He has only one thing to consider in performing any action; that is whether he is acting justly or unjustly.’ If he were offered acquittal – and with it his life – on the condition that he would refrain in future from the kind of philosophical enquiry he was accustomed to practise, he would refuse the offer. ‘I am not going (#litres_trial_promo) to alter my conduct, not even if I have to die a hundred deaths.’

There was an uproar in the court. Unabashed, Socrates reiterated his defiance, alluding to the passage in the Iliad when Thetis tells Achilles that if he re-enters the fighting he will die soon, for he is doomed to fall shortly after Hector. ‘“Let me die (#litres_trial_promo) forthwith,” said [Achilles], “… rather than remain here by the beaked ships to be mocked, a burden on the ground.” Do you suppose that he gave a thought to death and danger?’ The quotation was inaccurate but the sentiment was authentically Homeric. Achilles, like Socrates after him, refused to be a burden on the earth, a mere lump of animated matter, obedient to the stupid or immoral decrees of others. Wherever he went, Socrates told his judges, established authority would persecute him if he continued to question it, which he would never cease to do. A life in which he was not free to think and speak as he pleased was ‘not worth living’. To die was preferable.

A vote was called. Socrates was found guilty by 280 votes to 220. He spoke again. His accusers demanded the death penalty. According to Athenian law it was for the defendant to propose another, lesser punishment. Socrates believed, and most historians agree with him, that if he had asked for banishment it would have been granted. He disdained to do so. The sentence of death was voted on, and approved by a substantially larger majority than the verdict (indicating that there were more people in court who wanted Socrates dead than there were people who believed him to be guilty as charged). He spoke again, asserting that he was content because the satisfaction of acting rightly, according to one’s own lights of reason and moral discrimination, was so great as to eclipse any suffering: ‘Nothing can harm (#litres_trial_promo) a good man either in life or after death.’ Defiant, courageous, intransigent, he had proved himself equal to the example he had invoked in court, Achilles.

A man of violence who admitted himself to be easily bested in debate, whose passions were hectic, and whose thought processes were frequently incoherent, who spoke his mind at all times and despised subterfuge, Homer’s Achilles was in many ways a bizarre model for the philosopher who strove unceasingly to subject emotion to reason, who was a master of irony and a brilliant manipulator of men’s minds. But the classical philosopher and the legendary warrior were, for all their differences, soul-mates. Alexander, world-conqueror in the making, sought to associate himself with Achilles’ youthful valour and invincibility, with the glittering, deadly warrior whose brilliance rivalled the splendour of the midday sun. But when Socrates, the impecunious, pug-nosed, incorrigible old worrier of complacent authority and scourge of dishonest thinking, claimed Achilles as a predecessor he did so in appreciation of the fact that Achilles was more than a killer of unparalleled charisma, that he could be taken as a model in peace as well as in war, as one who insisted that his life should be worthy of his own tremendous estimation of his own value as an individual, and who would pay the price required to invest that life with significance and dignity, even if the price were life itself. Socrates defied convention and eventually fell foul of the law because he would submit to no other dictates than those of his intellect and of his private daimon. Achilles rebelled against Agamemnon’s overlordship, and looked on relentless while his countrymen were slaughtered rather than compromise his honour. Both were stubborn, self-destructive, exasperating to their enemies and the dismay of their friends. Both insisted on valuing their own personal integrity higher than any service or disservice they might do the community. Both have been condemned for their culpable pride, and venerated for their courage and their superb defiance.

In his tent at the furthest end of the Greek encampment, sworn to inaction, isolated by his own rage and by others’ fear of it, Achilles set himself at odds with the fractured, fudged-together thing that society necessarily is. Any human group, be it a family, a city, an army or a nation, depends for its continued existence on its members’ willingness to bend and yield, to compromise, to accept what is possible rather than demand what is perfect; but a society that loses sight of the standard of perfection is a dangerously unstable one. From the accommodating to the corrupt is an easy slide. Achilles and others who, like him, have stood firm, however wilfully and self-destructively, on a point of principle, have generally been revered by onlookers and by posterity as wholeheartedly as they have been detested by the authorities they challenge. ‘Become who you are! (#litres_trial_promo)’ wrote Pindar, Socrates’ contemporary. It is not an easy injunction. For a man to become who he is takes a ruthless lack of concern for others’ interests, monstrous egoism, and absolute integrity. Achilles, who hated a dissembler worse than the gates of death, had the courage to make the attempt, and so died.

II ALCIBIADES (#ulink_08480a80-7462-5075-8db2-0542f097c8af)

IN 405 BC the Peloponnesian War, which had lasted for a quarter of a century and set the entire Hellenic world at odds, ended with the comprehensive defeat of the Athenians at Aegosopotami on the Hellespont. The fleet on which Athens depended for its security and its food supply was destroyed. Lysander, commanding the victorious Spartans, had all the defeated Athenians troops slaughtered. The ship bearing the news reached the Athenian port of Piraeus at nightfall. The wailing began down in the harbour. As the news was passed from mouth to mouth, it spread gradually all along the defensive walls linking city to sea until it reached the darkened streets around the Acropolis and the whole city was heard to cry out like an enormous beast in its agony. ‘That night (#litres_trial_promo),’ wrote Xenophon, ‘no one slept. They mourned for the lost, but more still for their own fates.’

The Athenians had good cause to mourn. Within a matter of months they had been blockaded and starved into submission. Their democracy had been replaced by a murderous puppet government, an oligarchy known as the Thirty Tyrants. They lived in fear – of the Spartans who were now their overlords, and of each other, for every formerly prominent person was under suspicion, informers were so active that none dared trust his neighbour, and Critias, leader of the Thirty, ‘began to show (#litres_trial_promo) a lust for putting people to death’. And yet, according to Plutarch, ‘In the midst (#litres_trial_promo) of all their troubles a faint glimmer of hope yet remained, that the cause of Athens could never be utterly lost so long as Alcibiades was alive.’

Alcibiades! The name was a charm, and its workings, like all magical processes, were beyond reason. The man on whom the Athenians, in their extremity, pinned their hopes was one whom they had three times rejected, a traitor who had worked so effectively for their enemies that there were those who held him personally responsible for Athens’ downfall. Exiled from Athens for the second time, he was now living among the barbarians in Thrace. There, in a heavily fortified stronghold, with a private army at his command, he led the life of an independent warlord or bandit chief. There was no substantial reason to suppose that he could do anything for the Athenian democracy, and no certainty that he would wish to help even were it in his power to do so. And yet, as the first-century historian Cornelius Nepos noted, Alcibiades was a man from whom miracles, whether malign or beneficent, had always been expected: ‘The people thought (#litres_trial_promo) there was nothing he could not accomplish.’

Plato, who knew Alcibiades, elaborates in the Republic what he calls a ‘noble lie (#litres_trial_promo)’, a fable in which he suggests that all men are made from earth, but that in a few the earth has been mixed with gold, rendering them inherently superior to their fellow men, and fit to wield power. This lie, Plato suggests, is a politically useful one. In his ideal republic, he would like to ‘indoctrinate’ the mass of the people with a belief in it, in order that they might be the more easily governed. It would probably not be hard to do so. The belief that some people are innately different from and better than others pervades all pagan mythology and classical legend and surfaces as well in folk tales and fairy stories. The foundling whose white skin proclaims her noble birth, the favoured younger son who survives his ordeals assisted by the birds and beasts who recognize his privileged status, the emperor-to-be whose birth is attended by tremendous omens – all spring, as Plato’s men of gold do, from a profoundly anti-egalitarian collective belief in, and yearning for, the existence of a naturally occurring elite – exceptional beings capable of leading their subordinates to victory, averting evil and playing saviour, or simply providing by their prodigious feats a spectacle capable of exhilarating and inspiring the humdrum multitude. In Alcibiades the Athenians found their golden man.

That Alcibiades was indeed an extraordinary person is well attested. All his life he had a quality, which his contemporaries were at a loss to define or explain, that inspired admiration, fear, and vast irrational hopes. ‘No one ever (#litres_trial_promo) exceeded Alcibiades’, wrote Nepos, ‘in his faults or in his virtues.’ His contemporaries recognized in him something demonic and excessive that both alarmed and excited them. Plutarch likened him to the fertile soil (#litres_trial_promo) of Egypt, so rich that it brings forth wholesome drugs and poisons in equally phenomenal abundance. He was a beauty and a bully, an arrogant libertine and a shrewd diplomat, an orator as eloquent when urging on his troops as when he was lying to save his life, a traitor three or four times over with a rare and precious gift (essential to a military commander) for winning his men’s love. There was a time when his prodigious energy and talents terrified many Athenians, who feared that a man so exceptional must surely aim to make himself a tyrant; but in their despair they looked to him as a redeemer.

His adult life coincided almost exactly with the duration of the Peloponnesian War, which began in 431 BC, when he was nineteen, and ended with the fall of Athens in 405, the year before his death. Throughout that period, with brief interludes, the Spartans and their allies (known collectively as the Peloponnesians) struggled against the Athenians, with their allies and colonies, for ascendancy while lesser powers repeatedly shifted allegiance, tilting the balance of power first one way, then another. Sparta was a rigidly conservative state with a curious and ancient constitution in which two hereditary kings ruled alongside, and were outranked by, a council of grandees, the ephors, selected from a handful of noble families. Spartan colonies had oligarchic governments imposed upon them. Athens was a democracy, and founded democracies in its colonies. The war had an ideological theme, but it was also a competition between two aggressively expansionist rival powers for political and economic dominance of the eastern Mediterranean world. From 412 onwards it was complicated by the intervention of the Persians, whose empire dwarfed both the Hellenic alliances. Athens’ successful colonization of the Aegean islands and the coastal regions of Asia Minor deprived the Persian Great King of revenue. His regional governors, the satraps, sided first with the Spartans, later with Athens, in an attempt to re-establish control of the area. Alcibiades, who had Odysseus’ cunning as well as Achilles’ brilliance, was a skilful actor in the complex, deadly theatre of the war. As a general he was swift, subtle and daring. As a diplomat he proved himself to be a confidence trickster of genius.

In his youth he was the golden boy of Athens’ golden age. His family were rich, aristocratic (they claimed descent from Homer’s Nestor), and well connected not only in Athens but all over the Greek world. In constitutional terms every free male citizen of Athens was equal to every other, but in practice the nobility still dominated the government as they did the city’s economic and social life. Homer’s characters take it for granted that a person’s best qualities are inherited. ‘No mean men (#litres_trial_promo) could sire sons like you’, Menelaus tells two handsome young strangers (he’s right – their fathers are both kings). Most of Alcibiades’ contemporaries would have made the same assumption. ‘The splendour (#litres_trial_promo) running in the blood has much weight,’ wrote Pindar. When Alcibiades was still a child his father was killed in battle and he was taken to live in the household of his guardian Pericles, who was for thirty years effective ruler of Athens. He could scarcely have been given a better start in life.

Nature was as kind to him as fortune had been. Like Achilles, he was dazzlingly beautiful. To Plutarch, writing five hundred years after his death, his loveliness was still so much of a byword that ‘we need say (#litres_trial_promo) no more about it, than that it flowered at each season of his growth in turn’. In the homoerotic society of Athens such good looks made him an instant celebrity. As a boy, he was ‘surrounded and pursued (#litres_trial_promo) by many admirers of high rank … captivated by the brilliance of his youthful beauty’. Whether he actually had sexual relations with any of them is unclear, but gossip maintained that he did. If so, few of his contemporaries would therefore have considered him either immoral or effete. Aeschylus, in the generation before Alcibiades, and Plato, his contemporary, both believed Achilles to be Patroclus’ lover (something Homer does not suggest), but neither of them thought any the less of him for it. On the contrary, Plato’s Phaedrus cites Achilles’ ‘heroic choice (#litres_trial_promo) to go and rescue Patroclus’ as an example of the way in which love can ennoble a man, earning him ‘the extreme admiration of the gods’.

Among those smitten by Pericles’ ward was Socrates, who told a disciple that the two great loves (#litres_trial_promo) of his life were philosophy and Alcibiades. The philosopher had gathered around himself a group of aristocratic young men, non-paying students of whom Alcibiades was certainly not the most serious but of whom he was the most highly favoured. Plato (another of them) testifies that the relationship between the ugly middle-aged philosopher and the radiantly beautiful teenager remained chaste, but it surely was, at least on Socrates’ part, physically motivated. When in Plato’s Protagoras, which is set at a time when Alcibiades was about fifteen, Socrates claims to have become so engrossed in a philosophical discussion as to have briefly forgotten Alcibiades altogether, his friend teases him by saying ‘Surely you did not (#litres_trial_promo) find anyone else of greater beauty there. No! not in all our city.’ Alcibiades’ beauty marked him out, just as Achilles’ had done, as a superior being. In the second century ad the Roman Emperor Hadrian, a connoisseur and devotee of male beauty as ardent as any Athenian, set up an image of Alcibiades in Parian marble and commanded that an ox should be sacrificed to him every year. In his lifetime as well, his looks made him an object, not only of lust, but also of worship. And lovely as he was, his charm was as potent as his physical attractions. His personal magnetism, according to Plutarch, ‘was such that (#litres_trial_promo) no disposition could wholly resist it, and no character remain unaffected’. The events of his extraordinary career confirm the claim.

As a young man Alcibiades was showy, extravagant, outrageous. He wore his hair as long as a woman’s, spoke with a provocative lisp and strutted through the marketplace trailing his long purple robe. He was a ringleader, a setter of trends. Eupolis reports that he started a fashion for drinking in the morning. When he appeared in a new style of sandal all his contemporaries had copies made, and called them ‘Alcibiades’. He was proud and unbiddable, touchily conscious of his dignity as a nobleman. Plutarch relates an anecdote about him as a child playing in the street, first refusing to interrupt a game of dice in order to allow a cart to go by, and then lying down in the vehicle’s path to show his defiance of the driver’s threats, risking his life rather than take orders from a common carter. He refused to learn to play the flute, on the grounds that flautists made themselves look ridiculous by pursing their lips: flute-playing at once went out of fashion among the smart Athenian youth. As an adolescent, according to his son, he disliked the favourite Athenian sport of wrestling because ‘some of the athletes (#litres_trial_promo) were of low birth’. As an adult, he was a keen breeder and trainer of horses, an amusement open only to the rich. He carried himself as one who knows himself to be a superior being, by virtue of his class but also because his gifts fitted him for a splendid destiny and because his gargantuan vitality would settle for no less. Plato records Socrates saying to him: ‘You appear to me (#litres_trial_promo) such that if any god were to say to you “Are you willing, Alcibiades, to live having what you now do, or would you choose to die instantly unless you were permitted greater things?” you would prefer to die.’ Socrates was not talking about material possessions. ‘Further, if the same god said “You can be master here in Europe, but will not be allowed to pass over into Asia”, it appears to me that you would not even on those terms be willing to live, unless you could fill the mouths of all men with your name and power.’ Like Achilles, Alcibiades, according to those intimate with him, had no use for an unremarkable life.

The device on his extravagantly splendid ivory and gold shield showed Eros with a thunderbolt, an image, combining aggressive sexuality with elemental violence, that nicely encapsulates the impression he made. He was prodigally, flashily generous. It was customary for wealthy Athenians with political ambitions to woo the populace by subsidizing choral performances and other public shows: Alcibiades’ were always the most lavish. His first public action was, characteristically, the donation of a quantity of money to the state, and it was performed with typically insouciant theatricality. He happened to be passing the place of assembly at a time when citizens had been asked to make voluntary contributions to the treasury to meet the costs of the war. He was carrying a live quail under his cloak, but hearing the applause with which donors were being received he went in, pledged a large sum, and at the same time inadvertently released the bird. There was laughter and a scramble that ended in a seaman named Antiochus catching the quail and handing it back to Alcibiades. The meeting was to prove a fateful one. Antiochus’ next appearance in recorded history is in the role of catalyst for Alcibiades’ downfall. For the time being, though, he was assisting at an auspicious occasion, the public debut of the rich young dilettante whose mind was on sport but who had demonstrated that he could, if it happened to please him, be of substantial service to the state.

While still in his teens Alcibiades served his stint in the army, as all Athenians were required to do, sharing a tent with Socrates. Philosopher and disciple each acquitted themselves well, but when Socrates saved the younger man’s life, fighting off the enemy when he lay wounded, it was Alcibiades who was awarded a crown and suit of armour as a prize for valour – an injustice that owes something to Socrates’ selflessness, something to the generals’ snobbery, and something as well to Alcibiades’ frequently noted gift for gaining the credit for more than he had actually performed. His actions were as ostentatious as his appearance. ‘Love of distinction (#litres_trial_promo) and desire for fame’ were, according to Plutarch, the engines that drove him. But courageous he certainly was, and popular with both the common soldiers and those who commanded him.

Warfare provided an outlet for his prodigious energies. In civilian life, they festered. Cornelius Nepos praises his accomplishments and abilities but goes on: ‘but yet, so soon (#litres_trial_promo) as he relaxed his efforts and there was nothing that called for mental exertion, he gave himself again to extravagance, indifference, licentiousness, depravity’. He had voracious appetites, for sex, for drink, for luxury of all kinds, and he had the money to indulge them all. Already very rich himself, he married Hipparete, one of the wealthiest heiresses in Athens. The wedding seems to have scarcely interrupted his scandalous series of liaisons with courtesans. Scurrilous gossip later accused him of incest with his sister, mother, and illegitimate daughter. The charges are lurid and unconvincing (there is no other evidence that he even had a sister), but his reputation for promiscuity was undoubtedly well founded.

He was a high-handed swaggerer, someone by whom others were readily intimidated and who took pleasure in trying his power. He was jealous. Even Socrates said of him, albeit teasingly, ‘I am really quite scared (#litres_trial_promo) by his mad behaviour and the intensity of his affections.’ He was violent. As a boy he had beaten up a teacher who confessed to owning no copy of Homer’s works (an assault that was generally agreed – such was the mystique accorded the two epics – to redound to the perpetrator’s credit). He once struck his father-in-law simply for a wager. He thrashed a man who had dared to subsidize a chorus in competition with the one he himself had sponsored. He was rumoured to have killed a servant. When he wanted his house decorated with murals he abducted the distinguished painter Agatharchus, locked him up in the house until he had done the work, then sent him home with a cartload of gold. Annoyed by Anytus, one of the many older men who doted on him, he refused an invitation to dinner but then arrived at the party, late and visibly drunk, with a gang of slaves whom he ordered to seize half of the gold and silver vessels Anytus had laid out to impress his guests (only Athenaeus, of the several ancient writers to tell this story, softens it by mentioning that Alcibiades subsequently gave the valuable dishes to a needy hanger-on). When Hipparete, rendered desperate by her husband’s shameless infidelities, appeared before the magistrates to petition for a divorce, Alcibiades interrupted the proceedings, seized her, and carried her home through the marketplace, ‘and not a soul (#litres_trial_promo) dared oppose him or take her from him’. Such delinquency in one so high placed and privileged was unnerving. It threatened to disrupt not only the lives of his immediate circle, but of the whole community that observed him, fascinated and fearful. Timon, the notorious misanthrope, once accosted Alcibiades in the street, shook him by the hand, and said: ‘You are doing well (#litres_trial_promo), my boy! Go on like this and you will soon be big enough to ruin the lot of them.’

As befitted Pericles’ ward, he soon began to make his mark in the Assembly, displaying, according to the great Demosthenes himself, an ‘extraordinary power’ of oratory. Pericles had died in 429 BC. By 421 Alcibiades, though not yet thirty, was one of the two most influential men in the city. The other, Nicias, was in nearly every way his opposite. Older than his rival by twenty years, Nicias was cautious, timid, and notoriously superstitious. Alcibiades’ indiscretions were brazen; Nicias used to shut himself up in his house at night rather than waste time or risk being duped by a spy. Alcibiades liked to dazzle the public; Nicias was careful to ascribe his success to the favour of the gods in order to avoid provoking envy. Most importantly, Alcibiades saw the by now protracted war against the Spartans as a splendid opportunity for the aggrandisement of himself and of his city; Nicias longed only to end it.

In 421 BC he succeeded temporarily in doing so. He negotiated a treaty whereby the Peloponnesians and the Athenians agreed to exchange prisoners and to restore all of each other’s captured territory. But, as Plutarch records, ‘No sooner (#litres_trial_promo) had [Nicias] set his country’s affairs on the path of safety than the force of Alcibiades’ ambition bore down upon him like a torrent, and all was swept back into the tumult of war.’ There were disputes about the procedure for restoring the conquered cities and fortresses, disputes that Alcibiades aggravated and exploited. A Spartan delegation arrived in Athens. Alcibiades tricked them and undermined their standing, ensuring that the Assembly would refuse to deal with them and sending them home humiliated and enraged. Nicias followed after them but was unable to repair the damage: the Spartans rejected his overtures, the Athenians had lost their enthusiasm for the peace. Alcibiades was elected general (for one year, as was the custom). He forged an alliance with Mantinea, Elis, and Argos, and took Athens back to war.

There were those who accused him of making war for personal gain. Certainly there were prizes to be won which he would have welcomed. He had a reputation for financial rapacity. His father-in-law (or brother-in-law, accounts differ) was so afraid of him that he entrusted his enormous fortune to the state, lest Alcibiades might be tempted to kill him for it. He had already, after demanding a dowry of unprecedented size, extorted a second equally enormous sum from his wife’s family on the birth of their first child. His wealth was immense, but so was his expenditure. ‘His enthusiasm (#litres_trial_promo) for horse breeding and other extravagances went beyond what his fortune could supply,’ wrote Thucydides. Besides, in the Athenian democracy (as in several of the modern democracies for which Athens is a model), only the very rich could aspire to the highest power. Alcibiades needed money to pay for choruses, for largesse, for personal display designed, not solely to gratify his personal vanity, but to advertise his status as a great man.

But the war offered him far more than money. It provided him with a task hard and exhilarating enough to channel even his fantastic vitality, and it afforded an opportunity for him to satisfy the driving ambition Socrates had seen in him. Nicias, his rival, understood him well, and paid back-handed tribute to his eagerness for glory when he told the Athenian Assembly to ‘Beware of [Alcibiades] (#litres_trial_promo) and do not give him the chance of endangering the state in order to live a brilliant life of his own.’

As advocate for the war, Alcibiades was spokesman for the young and restless, and also for the lower classes. He probably belonged to one of the clubs of wealthy young Athenians, clubs that were generally (and correctly) suspected to be breeding-places of oligarchic conspiracy, but there is no evidence he had any such sympathies. Haughty and spectacularly over-privileged as he was, his political affiliations were democratic. In his personal life he defied class divisions. Homer’s lordly Achilles detests the insolent commoner Thersites, and in an extra-Homeric version of the tale of Troy he kills him, thus upholding the dignity of the warrior caste and silencing the mockery of the people. Alcibiades would not have done so. He earned the disapproval of his peers by consorting with actors and courtesans and other riffraff, and he was to remain friends for most of his life with Antiochus, the common seaman who caught his quail. Politically, he followed the example of his guardian Pericles in establishing his power base among the poorer people, who tended to favour war (which was expensive for the upper classes, who were obliged to pay for men and ships, but which offered employment, decent pay, and a chance of booty to the masses). According to Diodorus Siculus, it was the youthful Alcibiades who urged Pericles (#litres_trial_promo) to embroil Athens in the Peloponnesian War as a way of enhancing his own standing and diverting popular attention from his misdemeanours. Certainly Alcibiades would have learnt from observing his guardian’s career that, as Diodorus puts it, ‘in time of war (#litres_trial_promo) the populace has respect for noble men because of their urgent need of them … whereas in time of peace they keep bringing false accusations against the very same men, because they have nothing to do and are envious’.

The Athenian alliance was defeated in 418 BC at the battle of Mantinea, but its failure cannot be blamed on Alcibiades, whose term as general had elapsed. During the following years he loomed ever larger in the small world of Athens, menacing those who mistrusted him, dazzling his many admirers. Everything about him was excessive – his wildness, his glamour, his ambition, his self-regard, the love he inspired. In a society whose watchword was ‘Moderation in all things’ he was a fascinatingly transgressive figure, an embodiment of riskiness, of exuberance, of latent power. ‘The fact was (#litres_trial_promo)’, writes Plutarch, ‘that his voluntary donations, the public shows he supported, his unrivalled munificence to the state, the fame of his ancestry, the power of his oratory and his physical strength and beauty, together with his experience and prowess in war, all combined to make the Athenians forgive him everything else.’

The dinner party described in Plato’s Symposium, which contains the fullest contemporary description of Alcibiades, dates from this period. The host is the poet Agathon, who is celebrating having won the tragedian’s prize. As the wine goes round the guests take turns to talk about love. They are serious, competitive, rapt. At last it is Socrates’ turn. In what has proved one of the most influential speeches ever written he enunciates his deadly vision of a love divested in turn of physicality, of human affection, of any reference whatsoever to our material existence. He finishes. There is some applause and then – right on cue – comes a loud knocking at the door. There is an uproar in the courtyard, the sounds of a flute and of a well-known voice shouting, and suddenly there in the doorway is the living refutation of Socrates’ austere transcendentalism. The philosopher has been preaching against the excitements of the flesh and the elation attendant on temporal power. To mock him comes Alcibiades, wild with drink, his wreath of ivy and violets slanted over his eyes, flirtatious, arrogant, alarming, a figure of physical splendour and worldly pride forcing himself into that solemn company like a second Dionysus. No wonder, as Nepos wrote, Alcibiades filled his fellow Athenians ‘with the highest hopes (#litres_trial_promo), but also with profound apprehension’.

In 416 BC, when he was thirty-four, he entered no fewer than seven chariots in the games at Olympia, something no one, commoner or king, had ever done before him, and carried off three prizes. Euripides wrote a celebratory ode: ‘Victory shines (#litres_trial_promo) like a star, but yours eclipses all victories’. The games were far more than a sporting event: they were festivals of great religious and political significance attended by crowds from all over the Greek world. Alcibiades celebrated his triumph with superb ostentation, drawing on the resources of his far-flung clients and dependants, pointedly making a display of a network of personal influence spreading all the way across the eastern Mediterranean. ‘The people of (#litres_trial_promo) Ephesus erected a magnificently decorated tent for him. Chios supplied fodder for his horses and large numbers of animals for sacrifice, while Lesbos presented him with wine and other provisions which allowed him to entertain lavishly.’ Alcibiades was only a private citizen, but with his wealth and his pan-Hellenic connections he formed, on his own, a political entity that looked like rivalling Athens itself.

It was too much. On the plain before Troy, Achilles measured his status as an outstandingly gifted individual against Agamemnon’s regal authority. At Olympia, Alcibiades, in parading his wealth, his influence and his talent, seemed to be issuing a parallel challenge to the state of which he was part but which he threatened to eclipse. So, at least, his contemporaries understood the spectacle. He was accused of having the city’s gold and silver ceremonial vessels carried in his triumphal procession and of having used them at his own table ‘as if they were (#litres_trial_promo) his own’. Non-Athenians, maintained one of his critics, ‘laughed at us when they saw one man showing himself superior to the entire community’. Answering the grumblers, Alcibiades asserted that in making himself splendid he was doing a service to his country, that a city needs its illustrious men to personify its power. ‘There was a time (#litres_trial_promo) when the Hellenes imagined that our city had been ruined by the war, but they came to consider it even greater than it really is because of the splendid show I made as its representative at the Olympic games … Indeed this is a very useful kind of folly, when a man spends his own money not only to benefit himself but his city as well.’ Not everyone was convinced. After Alcibiades won another victory at the Nemean games, the great painter Aristophon exhibited a portrait of him. Any visual representation of him, it should be remembered, would have paid tribute to his striking beauty, and beauty, in fifth-century Athens, was commonly understood to make a man eligible for far more than mere sexual conquest. ‘This much is clear (#litres_trial_promo),’ wrote Aristotle in the next generation. ‘Suppose that there were men whose bodily physique showed the same superiority as is shown by the statues of the gods, then all would agree that the rest of mankind would deserve to be their slaves.’ The people crowded to see Aristophon’s painting, but there were those who ‘thought it a sight (#litres_trial_promo) fit only for a tyrant’s court and an insult to the laws of Athens’. There was no place within a democracy for an Alcibiades. ‘Men of sense (#litres_trial_promo)’, warned a contemporary orator in an address entitled ‘Against Alcibiades’, ‘should beware of those of their fellows who grow too great, remembering it is such as they that set up tyrannies.’

In the winter of 416–415 BC Alcibiades was at last presented with an adventure commensurate with his ambition. A delegation arrived in Athens from Sicily, asking the Athenians to intervene in a war between their own colonists there and the people of Syracuse, a colony and powerful ally of the Spartans. The careful Nicias put forward sound arguments against undertaking such a risky and unnecessary venture, but Alcibiades was all for action. According to Plutarch, he ‘dazzled the imagination (#litres_trial_promo) of the people and corrupted their judgement with the glittering prospects he held out’. All Athens caught his war fever. The young men in the wrestling schools and the old men in the meeting places sat sketching maps of Sicily in the sand, intoxicating themselves with visions of conquest and of glory. The projected invasion of Sicily was not expedient, it was not prudent, it was not required by any treaty or acknowledged code of obligation; but its prospect offered excitement, booty, and the intangible rewards of honour. In the Assembly, Alcibiades, the man of whom it was said that without some great enterprise to engage his energies he became decadent, self-destructive, and a danger to others, ascribed to the state a character to match his own: ‘My view is (#litres_trial_promo) that a city which is active by nature will soon ruin itself if it changes its nature and becomes idle.’ He argued that, like himself, Athens was the object of envy and resentment, impelled for its own safety to make itself ever greater and greater. ‘It is not possible for us to calculate, like housekeepers, exactly how much empire we want to have.’ At Olympia, he claimed, Alcibiades was identified with Athens. Now, in urging the war in Sicily, he was offering Athens the chance to identify with Alcibiades, to be, like him, bold and reckless and superbly overweening.

He won fervent support. Nicias, in a last attempt to halt the folly, pointed out that the subduing of all the hostile cities in Sicily would require a vast armada, far larger and more expensive than the modest expeditionary force initially proposed. But the Assembly had by this time cast parsimony as well as prudence to the winds. They voted to raise and equip an army and navy commensurate with their tremendous purpose. The generals appointed to command the expedition were one Lamachus, the appalled and reluctant Nicias, and Alcibiades.

The resulting host’s might was matched by its splendour. The captains (gentlemanly amateurs whose civic duty it was to outfit their own ships) had ‘gone to great expense on figure-heads and general fittings, every one of them being as anxious as possible that his own ship should stand out from the rest for its fine looks and for its speed’. Those who would fight on land had taken an equally competitive pride in their handsome armour. When the fleet lay ready off Piraeus it was, according to Thucydides, ‘by a long way (#litres_trial_promo) the most costly and finest-looking force of Hellenic troops that up to that time had ever come from a single city’.

On the appointed day, shortly after midsummer, almost the entire population of Athens went down to the waterfront to watch the fleet sail. A trumpet sounded for silence. A herald led all of the vast crowds on ship and shore in prayer. The men poured libations of wine from gold and silver bowls into the sea. A solemn hymn was sung. Slowly the ships filed out of the harbour, then, assembling in open sea, they raced each other southwards. All the onlookers marvelled at the expedition’s setting out, at ‘its astonishing daring (#litres_trial_promo) and the brilliant show it made’, and were awed by the ‘demonstration of the power and greatness of Athens’, and incidentally the power and greatness of Alcibiades, the expedition’s instigator and co-commander. This appeared to be a triumph to make his victory at Olympia seem trivial. But by the time he sailed out at the head of that great fleet, Alcibiades’ downfall was already accomplished. The brilliant commander was also a suspected criminal on parole. The Athenians, who had entrusted the leadership of this grand and perilous enterprise to Alcibiades, had given him notice that on his return he must stand trial for his life. In his story, the pride and the fall are simultaneous.

One morning, shortly before the armada was due to sail, the Athenians awoke to find that overnight all the Hermae, the familiar idols that stood everywhere, on street corners, in the porches of private houses, in temples, had been mutilated. A wave of shock and terror ran through the city. The Hermae represented the god Hermes. Often little more than crude blocks of stone topped with a face and displaying an erect penis in front, they were objects both of affection and of reverence. Thucydides called them ‘a national institution’. Now their faces had been smashed and, according to Aristophanes, their penises hacked off. The outrage threatened the Athenians at every level. The gods must be angry, or if not angry before they would certainly have been enraged by the sacrilege. It was the worst possible omen for the projected expedition. Besides, the presence in the city of a hostile group numerous enough to perpetrate such a laborious outrage in a single night was terrifying. There were panic-stricken rumours. Some believed that the city had been infiltrated by outside enemies – possibly Corinthians. Others asserted that the culprits were treacherous Athenians, that the desecration was the first manifestation of a conspiracy to overthrow the democracy. An investigation was launched. Rewards were offered to anyone coming forward with useful information and informers’ immunity was guaranteed. One Andocides accused himself and other members of his club, which may well have been an association of would-be oligarchs; but Thucydides (along with most other ancient sources) seems to have considered his confession a false one. ‘Neither then (#litres_trial_promo) nor later could anyone say with certainty who had committed the deed.’

In the atmosphere of panic and universal suspicion, other dark doings came to light. It was a fine time for the undoing of reputations. Alcibiades had many opponents. Nicias’ supporters resented his popularity. So did the radical demagogues, especially one Androcles, who was instrumental in finding, and perhaps bribing, slaves and foreigners ready to testify to the investigators. Three separate informers, apparently seeing one form of sacrilege as being much the same as another, told stories of the Eleusinian Mysteries being enacted, or rather parodied, at the houses of various aristocratic young men. On all three occasions Alcibiades was said to have been present, and at one he was alleged to have played the part of the High Priest. The punishment for such impious action could only be death.

The allegation was, and remains, credible. Fourteen years later Socrates was to die on a charge of failing to honour the city’s gods, a charge against which he scarcely deigned to defend himself, and Socrates had been Alcibiades’ mentor. It is unlikely the young general was devout in any conventional sense. Besides, Alcibiades’ ‘insolence’ and his readiness to breach taboos were well known. Gossip had it that he had even staged a mock murder (#litres_trial_promo), shown the corpse to his friends, and asked them to help conceal the crime. If he was ready to make a game of the solemnity of death, why should he be expected to stop short of blaspheming against the gods?

Whatever the truth, Alcibiades vociferously asserted his innocence, and declared his readiness to stand trial and clear his name. His opponents demurred. He was the charismatic leader of the expedition from which all Athenians were hoping for so much. His popularity was at its height. Thucydides writes that his enemies feared that the people would be over-lenient with him were he to come to trial. They probably feared more than that. ‘All the soldiers (#litres_trial_promo) and sailors who were about to embark for Sicily were on his side, and the force of 1,000 Argive and Mantinean infantry had openly declared that it was only on Alcibiades’ account they were going to cross the sea and fight in a distant land.’ The expeditionary force was, in effect, his army. To impeach him while it lay in the harbour would trigger a mutiny. To put him to death might well start a civil war. His accusers temporized. They did not wish to delay the fleet’s departure, they said. Alcibiades should sail, but the charges against him remained outstanding. On his return, whatever happened in Sicily, he must face his accusers.