По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

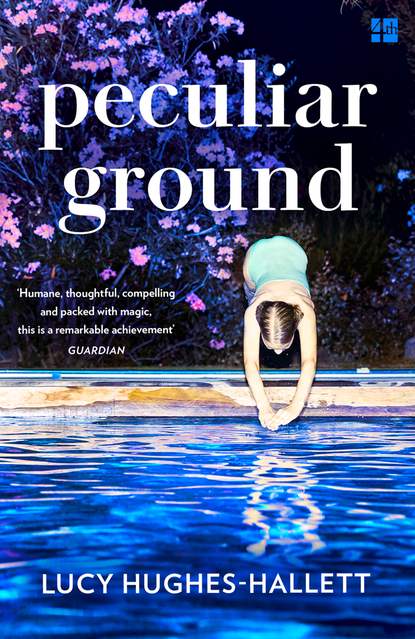

Peculiar Ground

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

As I write this, I feel myself to be quite a master of language, so why is it that, in conversation, words fall from my lips as ponderously as dung from a cow’s posterior? I will be the happier when the guests depart, and so, I fancy, may they be. Although the old portion of the house has not yet been invaded by the joiners and masons, the shouting emanating all day long from the wing under construction is an annoyance. And now that the work on the wall has begun, the park is encumbered with wagons hauling stone to every point on its periphery. The quarrymen set to at first light. We wake to the crack of stone falling away from the little cliff, and our days’ employment has as its accompaniment the clangour of iron pick on rock.

One congenial companion I have found. She is a young lady, not staying in the house, but frequently invited to enjoy whatever entertainment is in hand. She came to me boldly outdoors today.

I had been conferring with Mr Green, who is the chief executor of my wishes for the garden. He is, I consider, as worthy of the name of artist as any of the carvers and limners at work on the house – but because he is tongue-tied, those precious gentlemen are apt to treat him as a mere digger and delver. His own men show him the utmost respect.

Those goldfish that so put me out of countenance on my arrival have proved the seeds from which a delightful scheme has sprouted. The stony paving of the terrace is to be bisected by a canal, within whose inky water the darting slivers of pearl and orange and carnation will show as brilliant as the striped petals, set off by a lustrous black background, in the flower-paintings my Lord has brought home with him from Holland.

‘I hear, Mr Norris, you are rationalising Wychwood’s enchanted spring,’ said the lady.

‘You hear correctly, madam. Some small portion of its waters will trickle beneath the very ground on which you now stand. More will feed a fountain in the valley there, if Mr Rose and I can manage it.’

‘But have you appeased the genius loci, Mr Norris? You cannot afford to make enemies in fairyland.’

I was taken aback. I could not but wonder whether she teased. Were she any other young lady I would have been sure of it. But she is as simple in her manner as she is in her dress. Her name is Cecily Rivers.

*

‘I am glad you and my cousin are friends,’ Lord Woldingham said to me this morning as I spread out my plans for him. He is my elder by a decade, and inclined to mock me as though I were a callow boy. We were in the fantastically decorated chamber he calls his office. Looking-glasses, artfully placed, reflect each other there. When I raised my eyes I could not but see the image of the two of us, framed by their gilded fronds and curlicues, repeated to a wearisome infinitude. I, Norris the landskip-maker, in a dun-coloured coat. He, who will flutter in the scene I make for him, in velvet as subtly painted as a butterfly’s wing seen under a magnifying glass.

I do not much like to contemplate my own appearance. To see it multiplied put me out of humour. My Lord’s remark was trying, too. Often when it comes to time for inspecting the plans he finds some conversational diversion. I did not know whom he meant.

‘Your cousin, sir?’

‘My cousin, sir. You can scarcely pretend not to know her. Pacing the lawn with her half the afternoon. I have my eye on you, Norris.’

He made me uneasy. He loves to throw a man off his stride. In the tennis court, which abuts the stables, I have seen the way he will tattle on – this painter is new come to court and he must have him paint a portrait of his spaniel; this philosopher has a curious theory about the magnetism of planetary bodies – until his opponent lets his racket droop and then, oh then, my Lord is suddenly all swiftness and attention and shouting out ‘Tenez garde’ while his ball whizzes from wall to wall like a furious hornet and his competitor scampers stupidly after it.

I had no reason to fumble my words but yet I did so. ‘Mistress Rivers. Your cousin. I did not know of the relationship.’

‘Why no. Why would you, unless she chose to speak of it?’

‘She lives hereby?’

‘Hereby. For most of her life she lived here.’

‘Here?’

‘Yes. In this house. Cecily’s mother was not of the King’s party. She stayed and prospered under the Commonwealth while her brother, my father, wandered in exile.’

‘And now . . .’

‘And now the world has righted itself, and I am returned the heir, and my aunt is mad, and her husband is dead, and my cousin Cecily is delightful and though I do not think she can ever quite be friends with me, her usurper, she has made a playmate of you.’

‘Your aunt is . . .’

‘The quickness your mind shows when you are designing hanging gardens to rival Babylon’s, Mr Norris, is not matched by its functioning when applied to ordinary gossip. Yes. My aunt. Is mad. And lives at Wood Manor. Hereby, as you say. And Cecily, her sweet, sober daughter, comes back to the house where she grew up, in order to taste a little pleasure, and to divert her thoughts from the sadness of her mother’s plight.’

I must have looked aghast.

‘Oh, my dear Aunt Harriet is not wild-mad, not frenzied, not the kind of gibbering lunatic from whom a dutiful daughter needs protection. My aunt smiles, and babbles of green fields and is as grateful for a cup of chocolate as one of the papists, of whom she used so strictly to disapprove, might be for a dousing of holy water. I am her dear nevvie. She dotes on me. She forgets that I am her dispossessor.’

It is true that yesterday afternoon Miss Cecily and I walked and talked a considerable while on the lawns before the house. Had I known my Lord was watching us I might not have felt so much at ease.

*

It is Lord Woldingham’s fancy to enclose his park in a great ring of stone. Other potentates are content to impose their will on nature only in the immediate purlieus of their palaces. They make gardens where they may saunter, enjoying the air without fouling their shoes. But once one steps outside the garden fence one is, on most of England’s great estates, in territory where travellers may pass and animals are harassed by huntsmen, certainly, and slain for meat, but where they are free to range where they will.

Not so here at Wychwood. My task is to create an Eden encompassing the house, so that the garden will be only the innermost chamber of an enclosure so spacious that, for one living within it, the outside world, with its shocks and annoyances, will be but a memory. Other great gentlemen may have their flocks of sheep, their herds of deer, but, should they wish to control those creatures’ movements, a thorny hedge or palisade of wattle suffices. Lord Woldingham’s creatures will live confined within an impassable barricade. As for human visitors, they will come and go only through the four gates, over which the lodge-keepers will keep vigil.

Mr Rose took me today to view the first stretch of wall to have been constructed. He is justly proud of it. It rises higher than deer can leap, and is all made of new-quarried stone. When completed, it will extend for upward of five miles.

I said, ‘I wonder, are we making a second Paradise here, or a prison?’

‘Or a fortress,’ said Mr Rose. ‘Our King has had more cause than most monarchs to fear assassins. Lord Woldingham is courageous, but you will see how carefully he looks about him when he enters a room.’

‘His safety could be better preserved in a less extensive domain,’ I said.

‘He craves extension. He has spent years dangling around households in which he was a barely tolerated guest. There were times when he, with his great title and his claim on all these lands, had no door he could close against the unkindly curious, nor even a chair of his own to doze upon. He has been out, as a vagabond is out. Now, it seems, he chooses to be walled in.’

The wall is a prodigy. It will be monstrously expensive, but I am gratified to see what a handsome border it makes for the pastoral I am conjuring up.

*

This has been a happy day. It is never easy to foresee what will engage Lord Woldingham’s interest. I was as agreeably surprised by his sudden predilection for hydraulics as I had been saddened by his indifference to arboriculture. Having discovered it, I confess to having fostered his watery passion somewhat deviously, by playing upon his propensity for turning all endeavour into competitive games.

We were talking of the as-yet-imaginary lakes. I mentioned that the fall of the land just within the girdle of the projected wall was steep and long enough to allow the shaping of a fine cascade. At once he gave his crosspatch of a pug-dog a shove and dragged his chair up to the table. I swear he has never hitherto looked so carefully at my plans.

‘What are these pencilled undulations?’ he asked. I explained to him the significance of the contour lines.

‘So where they lie close together – that is where the ground is most sharply inclined?’ He was all enthusiasm. ‘So here it is a veritable cliff. Come, Norris. This you must show me.’

Half an hour later our horses were snorting and shuffling at the edge of the quagmire where the stream, having saturated the earthen escarpment in descending it, soaks into the low ground. My Lord and I, less careful of our boots than the dainty beasts were of their silken-tasselled fetlocks, were hopping from tussock to tussock. Goodyear and two of his men looked on grimly. If Lord Woldingham stumbled, it would be they who would be called upon to hoick him from the mud.

The hillside, I was explaining, would be transformed into a staircase for giants, each tremendous step lipped with stone so that the water fell clear, a descending sequence of silvery aquatic curtains.

‘And it will strike each step with great force, will it not?’

‘That will depend upon how tightly we constrain it. The narrower its passage, the more fiercely it will elbow its way through. This is a considerable height, my Lord. When the current finally thunders into the lake below it will send up a tremendous spray. Has your Lordship seen the fountain at Stancombe?’

Here is my cunning displayed. I knew perfectly well what would follow.

‘A fountain, Mr Norris! Beyond question, we must have a fountain. Not a tame dribbling thing spouting in a knot garden but a mighty column of quicksilver, dropping diamonds. I have not seen Stancombe, Norris. You forget how long I have been out. But if Huntingford has a magician capable of making water leap into the air – well then, I have you, my dear Norris, and Mr Rose, and I trust you to make it leap further.’

The Earl of Huntingford is another recently returned King’s man. Whatever he has – be it emerald, fig tree or fountain – my Lord, on hearing of it, wants one the same but bigger.

So now, of a sudden, I am his ‘dear’ Norris.

This fountain will, I foresee, cause me all manner of technical troubles, but the prospect of it may persuade my master to set apart sufficient funds to translate my sketches into living beauties. It is marvellous how little understanding the rich have of the cost of things.