По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

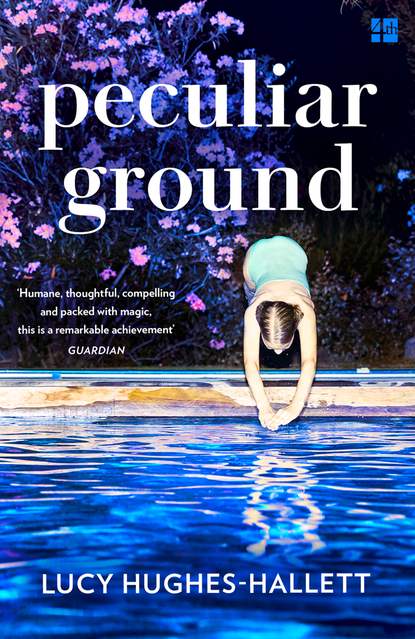

Peculiar Ground

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Benjie Rose – restaurateur, interior designer, entrepreneur

Helen Rose – his wife, art-historian

Guy – Benjie’s nephew, aged thirteen in 1961

On the estate

John Armstrong – head keeper

Jack Armstrong – his son, aged seventeen in 1961

Doris, Dorabella, Dorian and Dorothy – all spaniels

Green – head gardener

Young Green, his son

Brian Goodyear – head forester

Rob Goodyear, his son

Slatter – farm manager

Meg Slatter – his wife

Bill Slatter – their son

Holly Slatter – Bill’s daughter

Hutchinson – estate clerk

In the village

Mark Brown – cabinet-maker

Nell’s fellow students at Oxford in 1973

Francesca, Spiv Jenkins, Manny, Jamie McAteer, Selim Malik

In London

Roger Bates – wartime military policeman, subsequently in Special Branch

(#udec14449-5df4-591d-8085-fde11b8d3813)

1663 (#udec14449-5df4-591d-8085-fde11b8d3813)

It has been a grave disappointment to me to discover that his Lordship has no interest – really none whatsoever – in dendrology. I arrived here simultaneously with a pair of peafowl and a bucket full of goldfish. It is galling that my employer takes more pleasure in the creatures than he does in my designs for his grounds.

He is impatient. Perhaps it is only human to be so. He wishes to beautify his domain but he frets at slowness. When we talked in London, and I was able to fill his mind’s eye with majestic vistas, then he was satisfied. But when he sees the saplings reaching barely higher than the crown of his hat he laughs at me. ‘Avenues, Mr Norris?’ he said yesterday evening. ‘These are sticks set for a bending race.’

The idea having once occurred to him, he set himself to realising it. This morning he and another gentleman took horse and, like two shuttles drawing invisible thread, wove themselves at great speed back and forth through the lines of young beeches that now traverse the park from side to side. There was much laughter and shouting, especially as they passed the ladies assembled at the point where the avenues (I persist in so naming them) intersect, the trees forming a great cross which will be visible only to birds and to angels. I confess the gentlemen were very skilful, keeping pace like dancers until, nearing the point where the trees arrive at the perimeter, where the wall will shortly rise, they spurred on into a desperate gallop in the attempt to outdistance each other, and so raced on into a field full of turnips, to the great distress of Mr Slatter.

They are my Lord’s trees, his fields and his turnips. Like Slatter and his muddy-handed cohort, I must acknowledge the licence his proprietorship gives him, but it grieved me inordinately to find that eleven of my charges, my eight hundred carefully matched young beeches, have been damaged, five of them having the lead shoot snapped off. I attended him after dinner and informed him of the need for replacements. ‘Mr Norris, Mr Norris,’ he said. ‘It is hard for you to serve such a careless oaf, is it not?’

He authorised me to send for substitutes. He is not an oaf. Though it pained me, I took delight in the performance of this morning. He incorporated my avenue, vegetable and ponderous, into a spectacle of darting grace. But it is true that I find him careless. To him a tree is a thing, which can be replaced by another thing like it. Is it lunacy in me to feel that this is not so?

We who trade in landskips see the world not as it is but as it will be. When I walk in the park, which is not yet a park but an expanse of ground hitherto not enhanced but degraded by my work in it, I take little note of the ugly wounds where the earth has been heaved about to make banks and declivities to match those in my plan. I see only that the outline has been soundly drawn for the great picture I have designed. It is for Time to fill it with colour and to add bulk to those spare lines – Time aided by Light and Weather. I suppose I should say as well, aided by God’s will, but it seems to me that to speak of the Almighty in these days is to invoke misfortune. It is more certain and less contentious to note that Water also is essential.

*

Of the people who manage this estate my most useful ally has been Mr Armstrong, chief among my Lord’s rangers. For him, I believe, the return of the family is welcome. He is an elderly man, with the hooked nose and abundant beard of a patriarch. He remembers this house when the present owner’s father had it, and he rejoices at the thought that all might now be as it was before the first King Charles was brought down. I think he has not reflected sufficiently on how this country has changed in his lifetime, not only superficially, in that different regiments have succeeded each other, but fundamentally. It is true that there is once more a Charles Stuart enthroned in Whitehall, but the people who saw his father killed, and who lived for a score of years under the rule of his executioners, cannot forget how flimsy a king’s authority has proved.

Armstrong and Lord Woldingham talk much of pheasants – showy birds that were abundant here before the changes. Armstrong would like to see them strut again about the park. He has sent to Norfolk for a pair, and will breed from them. For him, I think, I am as the scenery painter is to the playwright. He is careful of me because I will make the stage on which his silly feathered actors can preen.

For Mr Goodyear, though, I am suspect. He is the curator of all of Wychwood’s mighty stock of timber. The trees are his precious charges. Some of them are of very great antiquity. He talks to them as familiars, and slaps their trunks affectionately when he and I stand conversing by them. I do not consider him foolish or superstitious: I do not expect to meet a dryad on my rambles, but I too love trees more than I care for most men. Goodyear is loyal to his employer, but it seems to me he thinks of those trees as belonging not to Lord Woldingham but in part to himself, his care for them having earned him a father’s rights, and in part to God. (I do not know to which sect he is devoted, but his conversation is well-larded with allusions to the deity.) He is ruddy-faced and hale and has a kind of bustling energy that is felt even when he is still. I will not enquire of him, as I do not enquire of any man, which party he favoured in the late upheavals, but I think him to have been a parliamentarian.

Today I walked with him down the old road that leads through the forest to the spring called the Cider Well. The road is still in use, but very boggy. ‘His Lordship would like to close it,’ said Goodyear. ‘I suppose he may do so if he wishes,’ I said. Goodyear made no reply. I have heard him allude to me as ‘that long lad’. I think he has judged me too young to be competent, and too pompous to be companionable.

Passing the spring, we dropped down into a valley, its mossy sides bright with primroses. The rabbits had already been at work on the new grass beneath our feet, so that the track was pleasant to walk upon.

A woman I had seen before – old but quick of step – was walking ahead of us. Goodyear called to her. She looked back over her shoulder, nodded to him, and then darted aside, taking one of the narrow paths that slant upwards, and vanished among the trees.

‘You know that person?’ I asked.

‘I’d be a poor forester if there were any soul in these woods without my knowledge.’

I ignored his pettish tone. ‘Does she live out here, then?’

‘She does.’

‘I encountered her in the park on Sunday. She made as though she wished to speak to me, but thought better of it.’

‘It’s best so. Don’t let her bother you, sir.’

I let the matter rest and began to talk to him of the plans I have discussed with Mr Rose, the architect. Rose is one of the many Englishmen of our age who, following their prince into exile, have grown to maturity among foreigners. There are constraints between such men and those of us who stayed at home and picked our way through the obstacles our times have thrown up. Rose and I deal warily with each other, but our work goes on harmoniously. In Holland Mr Rose interested himself in the Dutchmen’s ceaseless labours to preserve their country from the ocean to which it rightfully belongs. My Lord calls him his Wizard of Water.

We would build a dam where this pretty valley debouches into a morass, and thereafter a series of further dams. Thus contained and rendered docile, the errant stream will broaden into a chain of lakes. The three upper lakes will lie without the wall, as it were lost in the woods. The last watery expanse will be within the park and visible from the house, a glass to cast back the sun’s light and duplicate the images of the trees clumped about it.

It was as though Goodyear could see at once the prospect I sketched with my words, and soon we were in pleasant conversation. Willows, judiciously positioned, he rightly said, would bind the dams with their roots, and red alders might give shade. The ‘tremble-tree’, he suggested (I understood him to mean the aspen, a species of which I too am fond), ranged along the watery margins, would give a lightness to the picture, and his tremendous oaks, looming on the heights above, will take off the brashness of novelty, so that my lakes will glitter with dignity, like gaudy new-cut stones in antique settings.

How gratifying it would be to me, if I could enjoy such an exchange of ideas with his Lordship!

*

I could wish nutriment were not necessary to the human constitution, but alas, whatever else we be (and my mind swerves, like a wise horse away from a bog-hole, to avoid any thought that smacks of theology), we are indisputably animals, and animals must eat. My situation here is agreeable enough when I am in my chamber. In the drawing room – where Lord Woldingham expects me to appear from time to time – I am less easy. In the great hall where we dine I am wretched.

It is not the food that discommodes me, nor, to be just to the company, the mannerliness with which I am received. I am my own enemy. My self, of which I am pleasantly forgetful at most times, becomes an obstacle to my happiness. I do not know how to present it, or how to efface it. See how I name it ‘it’, as though my self were not myself. My Lord and his friends talk to me amiably enough. But the contrast between the laborious politeness with which they treat me, and the quickness of their wit in bantering with each other is painfully evident.