По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

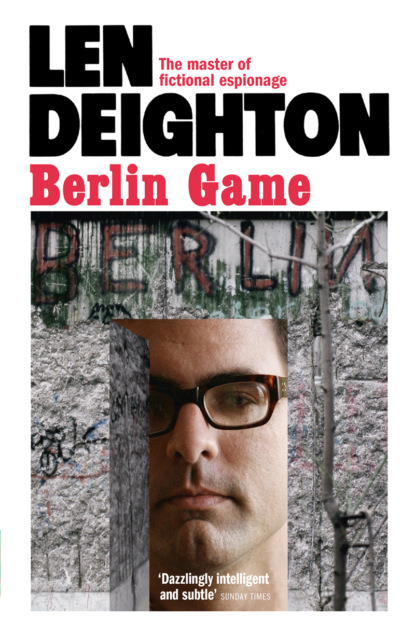

Berlin Game

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘All banks have an economics intelligence department. Being head of that department is not a job an ambitious banker craves for, so they get switched around. Brahms Four has been feeding us this sort of thing too long to be anything but a clerk or assistant.’

‘You’ll miss him. Too bad you have to pull him out,’ I said.

‘Pull him out? I’m not trying to pull him out. I want him to stay right where he is.’

‘I thought …’

‘It’s his idea that he should come over to the West, not mine! I want him to remain where he is. I can’t afford to lose him.’

‘Is he getting frightened?’

‘They all get frightened eventually,’ said Cruyer. ‘It’s battle fatigue. The strain of it all gets them down. They get older and they get tired and they start looking for that pot of gold and the country house with the roses round the door.’

‘They start looking for things we’ve been promising them for twenty years. That’s the truth of it.’

‘Who knows what makes these crazy bastards do it?’ said Cruyer. ‘I’ve spent half my life trying to understand their motivation.’ He looked out of the window. Hard sunlight sidelighting the lime trees, dark blue sky with just a few smears of cirrus very high. ‘And I’m still no nearer knowing what makes any of them tick.’

‘There comes a time when you have to let them go,’ I said.

He touched his lips; or was he kissing his fingertips, or maybe tasting the gin that he’d spilled on his fingers. ‘Lord Moran’s theory, you mean? I seem to remember he divided men into four classes. Those who were never afraid, those who were afraid but never showed it, those who were afraid and showed it but carried on with their job, and the fourth group – men who were afraid and shirked. Where does Brahms Four fit in there?’

‘I don’t know,’ I said. How the hell can you explain to a man like Cruyer what it’s like to be afraid day and night, year after year? What had Cruyer ever had to fear, beyond a close scrutiny of his expense accounts?

‘Well, he’s got to stay there for the time being, and there’s an end to it.’

‘So why was I sent to receive him?’

‘He was acting up, Bernard. He threw a little tantrum. You know the way these chaps can be at times. He threatened to walk out on us, but the crisis passed. Threatened to use an old forged US passport and march out through Checkpoint Charlie.’

‘So I was there to hold him?’

‘Couldn’t have a hue and cry, could we? Couldn’t give his name to the civil police and send teleprinter messages to the boats and airports.’ He unlocked the window and strained to open it. It had been closed all winter and now it took all Cruyer’s strength to unstick it. ‘Ah, a whiff of London diesel. That’s better,’ he said as there came a movement of chilly air. ‘But he’s still proving difficult. He’s not giving us the regular flow of information. He threatens to stop altogether.’

‘And you … what are you threatening?’

‘Threats are not my style, Bernard. I’m simply asking him to stay there for two more years and help us get someone else into place. Ye gods! Do you know how much money he’s squeezed out of us over the past five years?’

‘As long as you don’t want me to go,’ I said. ‘My face is too well known over there. And I’m getting too bloody short-winded for any strong-arm stuff.’

‘We’ve plenty of people available, Bernard. No need for senior staff to take risks. And anyway, if things went really sour on us, we’d need someone from Frankfurt.’

‘That has a nasty ring to it, Dicky. What kind of someone would we need from Frankfurt?’

Cruyer sniffed. ‘No need to draw you a diagram, old man. If Bee Four really started thinking of spilling the beans to the Normannenstrasse boys, we’d have to move fast.’

‘Expedient demise?’ I said, keeping my voice level and my face expressionless.

Cruyer became a fraction uncomfortable. ‘We’d have to move fast. We’d have to do whatever the team on the spot thought necessary. You know how these things go. And XPD can never be ruled out.’

‘This is one of our own people, Dicky. This is an old man who has served the Department for over twenty years.’

‘And all we’re asking,’ said Cruyer with exaggerated patience, ‘is for him to go on serving us in the same way. What happens if he goes off his head and wants to betray us is conjecture – pointless conjecture.’

‘We earn our living from conjecture,’ I said. ‘And it makes me wonder what I would have to do to have “someone from Frankfurt” come along to get me ready for that big debriefing in the sky.’

Cruyer laughed. ‘You always were a card!’ he said. ‘You wait until I tell the old man that one.’

‘Any more of that delicious gin?’

He took the glass from my outstretched hand. ‘Leave Brahms Four to Frank Harrington and the Berlin Field Unit, Bernard. You’re not a German, you’re not a field agent any longer, and you are far, far too old.’

He put a little gin in my glass and added ice, using claw-shaped silver tongs. ‘Let’s talk about something more cheerful,’ he said over his shoulder.

‘In that case, Dicky, what about my new car allowance? The cashier won’t do anything without the paperwork.’

‘Leave it to my secretary.’

‘I’ve filled in the forms already,’ I told him. ‘I’ve got them with me, as a matter of fact. They just need your signature … two copies.’ I placed them on the corner of his desk and gave him the pen from his ornate desk set.

‘This car will be too big for you,’ he muttered while pretending the pen was not marking properly. ‘You’ll be sorry you didn’t opt for something more compact.’ I gave him my plastic ballpoint, and after he’d signed I looked at the signature before putting the forms in my pocket. It was perfect timing, I suppose.

4 (#uf00f2f55-dd1c-5ede-8559-66e00437e784)

We’d arranged to visit Fiona’s Uncle Silas for the weekend. Old Silas Gaunt was not really her uncle; he was a distant relative of her mother’s. She’d never even met Silas until I took her to see him when I was trying to impress her, just after we’d first met. She’d come down from Oxford with all the expected brilliant results in philosophy, politics and economics – or ‘Modern Greats’ in the jargon of academe – and done all those things that her contemporaries thought smart: she studied Russian at the Sorbonne while perfecting the French accent necessary for upper-class young English-women; she’d done a short cookery course at the Cordon Bleu; worked for an art dealer; crewed for a transatlantic yacht race; and written speeches for a man who’d narrowly failed to become a Liberal Member of Parliament. It was soon after that fiasco that I met her. Old Silas had been captivated by his newly discovered niece right from the start. We saw a lot of him, and my son Billy was his godchild.

Silas Gaunt was a formidable figure who’d worked for intelligence back in the days when such service was really secret. Back in the days when reports were done in copperplate handwriting and field agents were paid in sovereigns. When my father was running the Berlin Field Unit, Silas was his boss.

‘He’s a silly little fart,’ said Fiona when I related my conversation with Dicky Cruyer. It was Saturday morning and we were driving to Silas’s farm in the Cotswold Hills.

‘He’s a dangerous little fart,’ I said. ‘When I think of that idiot making decisions about field people …’

‘About Brahms Four, you mean,’ said Fiona.

‘“Bee Four” is Dicky’s latest contribution to the terminology. Yes, people like that,’ I said. ‘I get the goddamned shivers.’

‘He won’t let the Brahms source go,’ she said. We were driving through Reading, having left the motorway in search of Elizabeth Arden skin tonic. She was at the wheel of the red Porsche her father had bought her the previous birthday. She was thirty-five and her father said she needed something special to cheer her up. I wondered how he was planning to cheer me up for my fortieth, coming in two weeks’ time: I guessed it would be the usual bottle of Remy Martin, and wondered if I’d again find inside the box the compliments card of some office-supplies firm who’d given it to him.

‘The Economics Intelligence Committee lives off that banking stuff that Brahms Four provides,’ she added after a long silence thinking about it.

‘I still say we should have stayed on the motorway. That chemist in the village is sure to have skin tonic,’ I said. Although in fact I hadn’t the faintest idea what skin tonic was, except that it was something my skin had managed without for several decades.

‘But not Elizabeth Arden,’ said Fiona. We were in a traffic jam in the middle of Reading and there was no chemist’s shop in sight. The engine was overheating and she switched it off for a moment. ‘Perhaps you’re right,’ she admitted finally, leaning across to give me a brief kiss. She was just keeping me sweet, because I was going to be the one who leaped out of the car and dashed off for the damned jar of magic ointment while she flirted with the traffic warden.

‘Have you got enough space in the back, children?’ she asked.

The kids were wedged each side of a suitcase but they didn’t complain. Sally grunted and carried on reading her William book, and Billy said, ‘How fast will you go on the motorway?’

‘And Dicky is on the committee too,’ I said.