По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

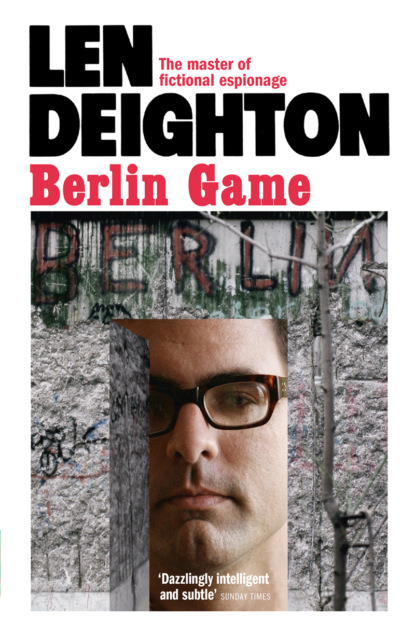

Berlin Game

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Further Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By Len Deighton (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Introduction (#uf00f2f55-dd1c-5ede-8559-66e00437e784)

Writers are frequently advised to shape their stories along conventional lines. This means simplify the plot-line, eliminate descriptive passages, emphasize and extend action, minimize characterization and forget sub-plots. This sort of well-intentioned advice is apt to transform a book into a film script. Not a bad move, you say. That’s true, unless you wanted to write a book.

Coming to writing at a time when the formalities of such instruction were unavailable I was likely to break one or the other of these rules: sometimes all of them in one go. I suppose many writers are drawn to the problems of characterization. That certainly was my prime interest; not just the characterization of the central characters but of spear-carriers too. Until Berlin Game I had fretted and struggled as I tried to retain the pace of the action while expanding the reality of the people in the story. To give my characters a real, or at least a convincing, life demanded more space. Did giving them a domestic dimension mean pressing the pause button in order to relate the dull routines of mortgages, electric bills, children’s ailments and traffic jams? No, that is not the way to treat your readers unless you just don’t care about them; and in that case you should be writing literary novels.

I have always been a planner. I remain in awe of writers who complete a book in ten days as friends of mine do. And even more wide-eyed to hear others proclaim that they customarily don’t know how their stories will end until they are writing the final chapter. I am far too timid for that kind of perilous pursuit.

My writing life is littered with the notes of abandoned stories, and Berlin Game had been balanced on the lid of the litterbin for a long time. The basic idea attracted me very much but there were problems that I’d not been able to crack. It was while on the final stages of Goodbye Mickey Mouse, a story about American fighter pilots flying out of England during the war, that I went back to some ideas about the man I came to call Bernard Samson. Goodbye Mickey Mouse had been described as ‘a romantic war story’ and although that seemed a surprising verdict at the time, I could not deny its validity. It was intended to be a book about a father and his son but for many readers the son’s love affair with his English girlfriend dominated the book. The meetings of a variety of English characters with equally varied American airmen were just as important as the air battles. Yet, more than once, I regretted not being able to integrate the English characters with the battlefield conditions at the airbase. Why hadn’t I cast the girlfriend as a nurse, or as a radio operator with an ear to the men fighting and dying? Well that was another sort of book, and it was just as well I didn’t write it because it was not the sort of book I wanted to read and that’s always a deciding factor.

But out of these ponderings came the idea that one could have a story in which wives and girlfriends were shoulder to shoulder with the fighting men. What about superior to them and in authority over them? And why not a spy story? I had a head filled with real-life espionage stories and Berlin was like a second home for me. I had good contacts on both sides of the Wall and my wonderful wife spoke German like a native. Now the domestic dimension would not be so domestic. Pillow talk would concern matters of life and death. Fidelity would not just be to the marriage vows but to the Official Secrets Act too. I scribbled these notes on the blank side of a US Air Force document that confirmed that I was physically fit enough to fly back-seat in a Phantom jet fighter. This was the beginning of Berlin Game.

I became so invigorated at the format I was drafting that I dismissed the idea of confining it to one book. What about a trilogy? Wait! What about two trilogies? Why not make a wall chart and see what it all looked like? That is what I did. This must not be a continuing series; all the books must be standalone stories, with no dependence on anything that had gone before or anything that might come afterwards. Impossible? No, just hard work.

Speaking as a reader of books rather than as a writer, I have always measured a book’s success by the way in which the characters were affected by events as the story progressed. This ‘development’, the way that experience changes the people in the story, is an important repayment to the reader for the time and effort he or she has given to you and your book. Change is not to be measured in elapsed time. For the Berlin family depicted in Winter almost half a century passed before the final page was completed. In Bomber, the airmen, and the German civilians under attack from the air, changed just as radically in little more than 24 hours.

So the prospect of planning and writing many books using the same characters (each of them aging and changing) was both attractive and daunting. They would grow older; perhaps wiser, or perhaps more foolish, or bitter. They would suffer setbacks and ailments; delight, sudden death and despair. And in fiction, as in real life, there was no going back. An inconvenient death in book number three was not something I could rectify in book number four. For all those reasons the writing of Berlin Game, the first book, required more preparatory work than any of the subsequent ones. Here were the people – the foundation – upon which the Bernard Samson stories would be built and balanced. Vague characterizations might have provided a way of keeping the options open. Better to start off with strongly realized people who would clash and caper according to rapidly changing events. Anyone who spent much time in Berlin’s eastern sector – and the Zone too – could not fail to see that Germany’s communist regime was shaky, although shaky regimes repressive enough sometimes continue for a long time. I certainly had no dates in mind but, as I have depicted in the books, there was a weakening of resolve and the regime was becoming more impoverished every day. Fundamentally agricultural, with no exports worth consideration, and a middle class with no income worth taxing, the DDR was a living corpse. I had previously written of the likelihood of the two Germanys becoming a Federation. The bureaucrats of both regimes were comparing pension plans and the border guards were shooting fewer escapers, which had to be a good sign. While people in the West were talking about, and even admiring the stability of the so-called German Democratic Republic, its rotten fabric was there for anyone who wasn’t wearing pink-coloured glasses. I was further convinced of all this when mingling with the drunks on Ascension Day and this is an experience that inspired the final chapters of Berlin Game. Collapse was sure to come eventually but little did I guess that the Wall would come down with such a spectacular crash. Telling the story of this amazing period was an opportunity that could not be ignored.

You can see what a wonderful life I have enjoyed. Melvyn Bragg once interviewed me and told the TV audience that I was the hardest working writer he had ever met. I was delighted; but he was wrong; I have never worked at all. Wrestling with the problems of writing books was like a holiday and the people I mixed with were a constant delight. ‘There are no villains in Deighton books,’ said one reviewer and other critics echoed this verdict. It was true. Finding somewhere, some redeeming feature of those we don’t much like, is a moral duty and a satisfying task.

Len Deighton, 2010

1 (#uf00f2f55-dd1c-5ede-8559-66e00437e784)

‘How long have we been sitting here?’ I said. I picked up the field glasses and studied the bored young American soldier in his glass-sided box.

‘Nearly a quarter of a century,’ said Werner Volkmann. His arms were resting on the steering wheel and his head was slumped on them. ‘That GI wasn’t even born when we first sat here waiting for the dogs to bark.’

Barking dogs, in their compound behind the remains of the Hotel Adlon, were usually the first sign of something happening on the other side. The dogs sensed any unusual happenings long before the handlers came to get them. That’s why we kept the window open; that’s why we were frozen nearly to death.

‘That American soldier wasn’t born, the spy thriller he’s reading wasn’t written, and we both thought the Wall would be demolished within a few days. We were stupid kids but it was better then, wasn’t it, Bernie?’

‘It’s always better when you’re young, Werner,’ I said.

This side of Checkpoint Charlie had not changed. There never was much there; just one small hut and some signs warning you about leaving the Western Sector. But the East German side had grown far more elaborate. Walls and fences, gates and barriers, endless white lines to mark out the traffic lanes. Most recently they’d built a huge walled compound where the tourist buses were searched and tapped, and scrutinized by gloomy men who pushed wheeled mirrors under every vehicle lest one of their fellow-countrymen was clinging there.

The checkpoint is never silent. The great concentration of lights that illuminate the East German side produces a steady hum like a field of insects on a hot summer’s day. Werner raised his head from his arms and shifted his weight. We both had sponge-rubber cushions under us; that was one thing we’d learned in a quarter of a century. That and taping the door switch so that the interior light didn’t come on every time the car door opened. ‘I wish I knew how long Zena will stay in Munich,’ said Werner.

‘Can’t stand Munich,’ I told him. ‘Can’t stand those bloody Bavarians, to tell you the truth.’

‘I was only there once,’ said Werner. ‘It was a rush job for the Americans. One of our people was badly beaten and the local cops were no help at all.’ Even Werner’s English was spoken with the strong Berlin accent that I’d known since we were at school. Now Werner Volkmann was forty years old, thickset, with black bushy hair, black moustache, and sleepy eyes that made it possible to mistake him for one of Berlin’s Turkish population. He wiped a spyhole of clear glass in the windscreen so that he could see into the glare of fluorescent lighting. Beyond the silhouette of Checkpoint Charlie, Friedrichstrasse in the East Sector shone as bright as day. ‘No,’ he said. ‘I don’t like Munich at all.’

The night before, Werner, after many drinks, had confided to me the story of his wife, Zena, running off with a man who drove a truck for the Coca-Cola company. For the previous three nights he’d provided me with a place on a lumpy sofa in his smart apartment in Dahlem, right on the edge of Grunewald. But sober, we kept up the pretence that his wife was visiting a relative. ‘There’s something coming now,’ I said.

Werner did not bother to move his head from where it rested on the seatback. ‘It’s a tan-coloured Ford. It will come through the checkpoint, park over there while the men inside have a coffee and hotdog, then they’ll go back in to the East Sector just after midnight.’

I watched. As he’d predicted, it was a tan-coloured Ford, a panel truck, unmarked, with West Berlin registration.

‘We’re in the place they usually park,’ said Werner. ‘They’re Turks who have girlfriends in the East. The regulations say you have to be out before midnight. They go back there again after midnight.’

‘They must be some girls!’ I said.

‘A handful of Westmarks goes a long way over there,’ said Werner. ‘You know that, Bernie.’ A police car with two cops in it cruised past very slowly. They recognized Werner’s Audi and one of the cops raised a hand in a weary salutation. After the police car moved away, I used my field glasses to see right through the barrier to where an East German border guard was stamping his feet to restore circulation. It was bitterly cold.

Werner said, ‘Are you sure he’ll cross here, rather than at the Bornholmerstrasse or Prinzenstrasse checkpoints?’

‘You’ve asked me that four times, Werner.’

‘Remember when we first started working for intelligence. Your dad was in charge then – things were very different. Remember Mr Gaunt – the fat man who could sing all those funny Berlin cabaret songs – betting me fifty marks it would never go up … the Wall, I mean. He must be getting old now. I was only eighteen or nineteen, and fifty marks was a lot of money in those days.’

‘Silas Gaunt, that was. He’d been reading too many of those “guidance reports” from London,’ I said. ‘For a time he convinced me you were wrong about everything, including the Wall.’

‘But you didn’t make any bets,’ said Werner. He poured some black coffee from his Thermos into a paper cup and passed it to me.

‘But I volunteered to go over there that night they closed the sector boundaries. I was no brighter than old Silas. It was just that I didn’t have fifty marks to spare for betting.’

‘The cabdrivers were the first to know. About two o’clock in the morning, the radio cabs were complaining about the way they were being stopped and questioned each time they crossed. The dispatcher in the downtown taxi office told his drivers not to take anyone else across to the East Sector, and then he phoned me to tell me about it.’

‘And you stopped me from going,’ I said.