По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

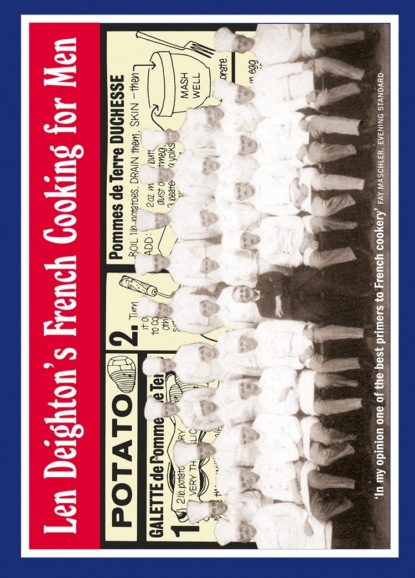

Len Deighton’s French Cooking for Men: 50 Classic Cookstrips for Today’s Action Men

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Perhaps the best barrier of all, especially for fragile foods or juicy foods like raw meat, is a simple batter (use recipe on page (#litres_trial_promo), but make it a little thicker so it’s like heavy cream).

As I have said, in France food is either sautéed with an absolute minimum of fat or deep-fried. A fried egg would be deep-fried in France. If you want to do deep-fat frying – and it’s by no means essential – then it will cost you time, trouble and money. Keep the pan clean and the fat filtered through a cloth between each batch of cooking. Store the fat in the cool when it’s not in use. Darkened oil has been used enough – throw it away. Fat that has been burned must be thrown away.

Still not discouraged? Then here’s some last advice. Deep-fried food tastes best if served immediately after cooking. Put it on hot plates and don’t put a lid over it because the hot air trapped around the food will make the crisp coating go limp. Absorbent paper will remove excess fat from the surface of the food before it goes to the table.

Those first four methods of cookery are suited to meat that will be served with its centre underdone (i.e. first-quality cuts and finely chopped meat). The following cooking methods are for cheaper cuts that will be served cooked right through.

VERY MOIST HEAT

In English cookery there is a method of cooking meat called ‘pot-roasting’. Its equivalent in French cooking is braising. A piece of meat is put inside a close-fitting pot with a heavy lid (the lid has no air vent). Little or no moisture is added but usually there are some vegetables. Heat is applied to the pot by any means you like; this causes the moisture inside the raw food to heat up and this cooks the food. If you are applying heat from underneath the pot you will have to turn the contents over every half an hour because the food will be hotter at the bottom. So it’s easier to put the whole pot inside an oven where there’s no need to turn the contents over because the heat is all around the pot. Whatever sort of heat you apply it will have to be gentle or else you will dry up all the moisture in the food and burn it. (Originally the pot had hot ashes and charcoal heaped upon it.) Pot-roasted joints are usually cheaper foods, such as boiling-chicken or the cheaper cuts of beef which are eaten well cooked. For best results keep the oven temperature very low, i.e. not above 300ºF. (150ºC.), and allow a long cooking time.

Most cooks put a large knob of fat into the pot and fry the outside of the meat to make it brown before beginning to cook it. A few large chunks of onion or carrot provide extra moisture and extra flavour. For a more complex addition try the mirepoix described on pages (#litres_trial_promo). The French cook will always be very attentive when cooking in this way. He looks into the pot and dribbles a spoonful of stock over the meat. The meat must never stand in a pool of water or stock, it must be moist enough and hot enough to make its own steam. Maximum amount of basting with the minimum amount of liquid is the rule. See pages (#litres_trial_promo), and, for vegetables braised, pages (#litres_trial_promo).

Another way of using this same technique is to wrap a piece of food in heavy paper (or the transparent plastic ‘roasting bag’) and put it into a gentle oven. This food too cooks in its own moist heat. This is called cooking en papillotes and is described on pages (#litres_trial_promo).

STEWING

This is cooking done by circulating liquid. The liquid circulates because the pot is standing upon heat which causes the heated water to rise, move around, and cook the whole thing evenly by convection. Usually the food is cut into pieces because that speeds the process and releases more flavour into the liquid. (In this cooking method it doesn’t matter if flavour escapes from the meat.) Sometimes the meat is left in one large piece but as long as the liquid is free to circulate, it’s a stew. Fricassée, pages (#litres_trial_promo), is a stew. A heavy thickened mixture in which the liquid does not circulate is not a stew, it is braising and should be cooked in the oven. Stews can be solely protein foods, e.g. chicken, beef, fish, or veal, or can have vegetables such as carrots, potato, and onion added to them during the last part of the cooking time so it will all be ready together. In any case stews must be cooked slowly and gently – faire cuire doucement – and never be allowed to boil or bubble. About 180ºF. is ideal. Keep meat pieces equal size then they’ll all take the same time to cook. Total weight of meat used makes no difference, it’s the size of the cubes that counts. Leg of beef, the cheapest cut there is, will need about four hours; chuck steak, a medium-price cut, a little over two hours. The cheaper cut will be better flavoured and the streaks of connective tissue, which look horrible when you are cutting it up, will dissolve with long cooking and become a rich gravy. This body or texture – du corps – of the stew is a sign of a cook’s skill. Some cooks try to get it by artificial means, e.g. stirring in a little flour or a little potato that goes mashy. That’s terrible, try to avoid it. Get the texture by ingredients. For extra body add something that will give you texture, e.g. veal knuckle, pig’s foot, chicken feet, tripe, or oxtail, then discard it before serving.

It’s usual to add some flavouring matter to the stew liquid; onion, garlic, herbs, bacon, or ham. If you fry such items in olive oil the heat will bring out the flavour and the oil will add one of its own.* (#litres_trial_promo) For a stronger flavour, part of the liquid is sometimes replaced by wine. Sometimes the cook is only concerned with the flavour of the liquid, intending to discard the meat finally and use only the stock. If you compare pages ref1 (#litres_trial_promo) and ref2 (#litres_trial_promo) you will see that the only difference between the finest way of making stock and the classic recipe for the French dish pot-au-feu is that in the latter you use a better-looking cut of meat.

In these notes about stewing I have concentrated on meat, but fish makes wonderful stews. Mix various types of sea fish to make bouillabaisse and various types of fresh-water fish to make matelote. If you are inventing a stew, beware of oily types of fish. Put the softest sort of fish pieces in last because they will cook more quickly. For best results have a little of various kinds. In any case fish stews will cook in less than half an hour, so go ahead, there’s time to invent a stew.

BOILING AND POACHING

Both words mean cooking in water on top of the stove, but the temperatures are different. The French are more precise in their words: when water is heated enough to shiver – frémir – it is just right for poaching – pocher; when it gets hotter there will be a bubble now and again at the same place. That is called mijoter and as far as the cook is concerned the water is boiling. (Beware, the cook seldom wants anything boiling.) If the water gets very hot it will go into a great rolling boil – bouillir – which is fine for reducing the volume of liquids but not for very much else.

Many dishes are called boiled but very few are actually boiled. (This word usually indicates that the liquid in which the food is cooked will not be served with it, i.e. boiled bacon, boiled mutton, etc.) Foodstuffs that are actually put into boiling water include eggs in their shells, vegetables, dried vegetables, cereals, and a few flour mixtures like pasta, suet puddings, and dumplings. Of these only the flour mixtures wouldn’t be just as good if cooked more slowly. (That’s because there are air particles which must be kept hot or they will collapse just as in baking pastry or cake.)

Most foods are best poached, i.e. kept at that gentle simmer or frémir as in poaching an egg. In English cookery it is very often the salt meats that are cooked in this way: salt beef, salt pork, bacon, and ham; that’s because immersion in water takes some of the salt taste out of them. Originally such foods were salted for the winter as a way of preserving them. By the time they were used they were very salty and needed a soaking in cold water before they were cooked. If you take my mother’s excellent advice about salt meat you will choose a suitable piece of meat and then ask your butcher to salt it in his brine tub. This will take about three days. After this brief salting it shouldn’t need any soaking, just go ahead and cook it. Don’t buy salt meat at random from the brine tub because the butcher sometimes consigns his old unsold meat to it and if it’s been in there too long it will be excessively salty. The standard rule for cooking salt meat: twenty-five minutes per pound plus twenty-five minutes. However I find that long cooking improves it and I suggest a four-hour minimum for any large piece. You need a pan big enough for the meat to just float and the water to circulate freely.

The French cook is not fond of salt meat; perhaps that has something to do with having a less severe winter and therefore not having to slaughter the animals at the winter solstice. More likely it’s because the liquid in which salt meat has been cooked is quite unusable as stock. With unsalted meat, however, the cooking liquid is served alongside as a soup; see pot-au-feu (pages (#litres_trial_promo)). Clever frugal French. There’s more about poaching on pages (#litres_trial_promo).

CUISSON AU BAIN MARIE

If you put a basin of water inside a saucepan of boiling water, you will find it very difficult to bring the water in the basin to the boil, no matter how furiously you heat the saucepan. The basin will remain at the same temperature, 180º–90ºF., which is right for most cookery; so you can braise, poach, or stew using this type of gadget. All the double-boiler does is make braising, poaching, or stewing easier. It’s a way of cooking delicate mixtures, e.g. egg custard and those sort of thick stews that are too solid to circulate (that daube on page (#litres_trial_promo) would be too solid). In fact that type of stew is commonly called a hot-pot because it stands in a saucepan of water. The terrine on page (#litres_trial_promo) is also a type of double-boiler.

This is one of the most perfect ways of cooking. It requires very little attention – just making sure the saucepan doesn’t boil dry – and because the rate of cooking is slow the time factor isn’t too vital. Sometimes the inner container has a tight-fitting lid. (In the case of apple pudding and steak pudding the food is encased and sealed in suet pastry.) Because blood, being protein, curdles at 176ºF. this is the way jugged hare should be cooked. Superior types of stew can be cooked this way, so can eggs en cocotte (page (#litres_trial_promo)); in fact anything can be cooked this way, even large pieces of meat.

Some ovens can be adjusted to give heat below the boiling point of water – 212ºF. – and obviously a pot inside such an oven will get exactly the same sort of heat as a double-boiler. Such cooking is called étuver. It is often used for vegetables cooked with butter.

STEAMING

The process of steaming provides a vivid chance to see the difference between heat and temperature. Put your hand into the hot air of an oven at 212ºF. and you’ll feel no more than discomfort but I advise you not to plunge your hand into water that is at this (boiling) temperature. Hot water is more violent than hot air and more violent than steam. A potato cooked in the dissipated heat of a steamer will take longer to cook than one that is boiled.

Steaming is done by putting food into a perforated container and placing that over a saucepan of boiling water. Only the steam touches the food. Sometimes egg mixtures – like custards – are steamed and they are much better than the same mixture boiled. Sometimes cooks making a pudding in a basin will stand it in simmering water so that the bottom part of it cooks double-boiler method and the top – pastry – part steams. Diabolical English cunning this. (Because this is a popular way to prepare English steak and kidney pudding, cooks often say steamed when they really mean this two-part way of cooking.)

PRESSURE COOKING

Pressure cooking is a special way of cooking at high temperature (226ºF.). Although it will cook fragile things, it is at its best when neither overcooking nor violent movement of air will affect the food. Soups, stocks, stews, and vegetables that will end up as a purée (e.g. swede, potato, turnip) are particularly good. So are any dried fruits or vegetables or suet puddings. A pressure cooker – marmite à pression – is a valuable tool for any cook who is short of time, even if it’s only used to make soup and stock. Read the instruction book that comes with it.

Although I like pressure cookers it must be added that a good cook should plan in advance, and stock that has simmered for five hours without attention is scarcely more bother than a pressure cooker that needs close attention for thirty minutes. The simmered stock will be far better and less cloudy.

Finally In the section on steaming, a paragraph or so back, I described how a steak pudding can enjoy being half steamed and half double-boiler cooked. That’s a clever and logical way to cook that dish because it is two entirely different foodstuffs being cooked in a method suited to each, i.e. pudding steamed, meat double-boiler cooked. However there are many other combination methods of cooking that stem from muddled thinking and are not logical or clever. For instance, it’s not logical and clever to have a joint of meat standing in a tray of fat in a hot oven: if you want it baked, then why have it in a tray of fat; if you want it fried, why have it in the oven? Another muddled cooking method is braising (see Very moist heat, page (#ulink_90e49805-9fec-5d84-9b57-c22c91a1bbf6)) which has so much moisture in it that the bottom half is stewing. Do whatever is best but not both together. Even more common is the cross between sautéing and frying. This is probably due to the popularity of eggs and bacon because the eggs are best deep-fried and the bacon is best sautéed. To save time and trouble most British cooks have their fat about an eighth of an inch deep for everything they fry. This is too shallow for cooking eggs and yet so deep that it swamps the bacon. Like most compromises it’s the worst of both worlds.

Now that you know all the ways to cook you should be able to apply them to any chunk of food that stands in front of you.

A potato will lend itself to roasting or baking. Sliced up it can be sautéed, fried, put into a stew, boiled, poached, steamed, pressure-cooked, and, although it’s unusual, pot-roasted or double-boiler cooked too. As long as you bear in mind the limitations of protein foods you can do anything any way. The only limit I would put upon you is that of using good-quality meat for the first four heating methods – dry radiant heat, oven heat, sauté, and frying.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: