По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

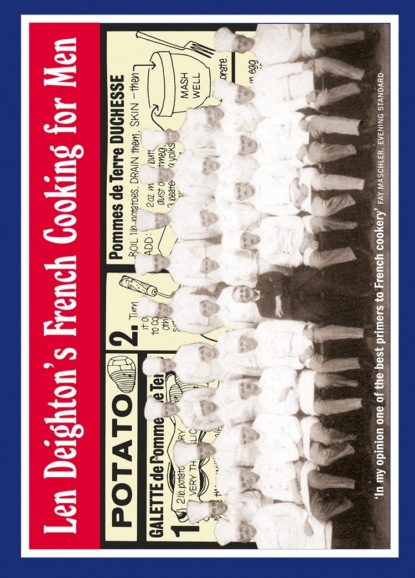

Len Deighton’s French Cooking for Men: 50 Classic Cookstrips for Today’s Action Men

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Meat, fish and poultry are the basic protein foods. All such flesh foods contract, dry and then harden, with cooking. Such protein foods cooked under a grill or broiler are served juicy and only partly cooked. Because only choice, expensive cuts are tender when under-cooked these are the ones chosen for the fierce heat of the grill or barbecue.

Flesh foods cooked in liquid will also harden. But after hardening they will break up, and eventually disintegrate, as the connective tissue disolves. Some cuts of meat have so much connective tissue that they can be cooked to a point where the disintegration resembles tenderness. For example try cooking a shoulder of lamb or mutton for five hours at 250ºF.

Egg and fish are also protein foods but they are much softer than meat, so although they will harden above boiling point they will not be rendered inedible. But a fresh new-laid egg will still taste better below boiling point than above. Eggs subjected to brisk heat (e.g. omelette) are best served only partly cooked, i.e. still moist and soft in the centre.

FAT

Fat occurs naturally in animal tissue. When meat is heated the fat melts and becomes dripping. Dripping always has a great deal of flavour so the cook uses it with care. There are all kinds of refined fats on the market: vegetable fats, vegetable oils, olive oil and butter. When fat is used as part of the texture of food, e.g. rubbed into pastry, cake mixtures, sponge, etc., the cook is most concerned with its flavour, but when the fat is used as a cooking medium – frying and sautéing – then the choice is based upon the temperature at which it burns. Even the fat which burns most easily – butter – can go much hotter than boiling water. On page (#litres_trial_promo) I have listed the burning points of various fats so you can compare them with the boiling point of water. N.B. When you are cooking in butter its burning point can be raised by adding a little oil.

FLOUR

When heat is applied to flour it goes hard. Very, very hard. If you mix flour and water and then cook it, it will become rock-like, so the cook makes sure that things made with flour have plenty of tiny air particles in them.

The glutens in flour which produce the starch provide the cook with a binding – liaison – an ingredient that will thicken liquids. If you stir a little cold water into an ounce of flour and go on pouring and stirring until you have half a pint of mixture you will have made a liaison à la meunière. If you apply heat to it, it will begin to thicken – keep stirring and don’t let it boil. After three minutes’ simmering the flour will have glutenized, it will be as thick as it gets and the floury taste will have disappeared. You have made a sauce. It won’t be a very interesting sauce, but if you had used flavoured water or even milk it would have been a real sauce.

Because fat can be made much hotter than water the cook usually glutenizes the flour in butter and then adds the water or etc. This combination of fat + flour is called a roux; it’s described further on pages ref1 (#litres_trial_promo) and ref2 (#litres_trial_promo).

SUGAR

Sugar caramelizes when heated. It turns a golden yellow, then light brown and, according to the amount of heat you apply, eventually black and burned.

VEGETABLES

Vegetables soften when heated by the cook. They don’t contain protein so you can boil them furiously if you want to. Frying is hotter than boiling and so when you fry vegetables you will see the sugar in them caramelize. Fried onions will, with a little heat, lose their capacity for making your eyes water, then they will soften and after that go a golden colour, then brown. Now they have taken on quite a different flavour. The cook sometimes uses this caramelization of onions etc. to add flavour and/or colour to a stew.

EGG

Egg is protein. All protein hardens above boiling point. Although egg is often given a blast of fierce heat we usually eat them only partly cooked. Omelettes, scrambled eggs, poached eggs, boiled eggs are given just enough heat to make them firm. Cook them longer and you’ll find yourself in the plastics industry.

High temperature releases hydrogen sulphide (from the sulphur in the egg-white) and makes an egg taste stale. This same sulphur combines with iron in the yolk to make that grey ring round the yolk of a hard-boiled egg that has been made too hot. So you see that a real boiled egg is unattractive, indigestible and tastes disgusting.

Although a ‘boiled egg’ goes into boiling water, do not bring it back to boiling point. Keep the water well below boiling temperature so that the surface just moves (the French say frémir which means to shiver and perfectly describes it). The water is now at about 185ºF.

The most satisfactory way to cook the egg in its shell is the old-fashioned method of ‘coddling’. Bring a pint of water to maximum boil. This rolling confusion of water, changing to steam, is nearly at 212ºF. Put one egg into the water, put a lid on the saucepan and turn off the heat. After approximately six minutes, eat it. I say approximately because the freshness of the egg influences the cooking time, and you might need to modify your cooking times to find the right one for your eggs, and your taste. Measure the amount of water you use, and provide one pint of water per egg. And from now onwards, remember how to estimate water temperature.

The egg is also a liaison, used, as flour is, to bind liquids into a sauce. But while flour is tough enough to withstand boiling, the protein of the egg curdles at 167ºF., and your sauce collapses. So when there is egg in your sauce be cautious. Heat it gently, and if possible cook it in a double-boiler (a basin over a saucepan of water will do). But there is a way of cheating – add a trace of flour to the egg and the sauce will withstand boiling, if you bring it to the boil slowly.

ALCOHOL

When wine or spirits are used in cooking they must be subjected to considerable heat or they will be very indigestible. Unless alcohol is set on fire, or has over one hour’s cooking at any temperature, it should be boiled until half its bulk has evaporated.

WATER

Water is perhaps the most important of all things subjected to the heat of cooking because all foods contain water. About 60 per cent of the weight of meat is water. Fish is 65–80 per cent water and vegetables and fruit 85–95 per cent water. (Foods that don’t contain water, e.g. dried fish, dried peas and beans, rice, etc., won’t go bad, because the bacteria in water cause that, but they will need water added to them again before being cooked.)

When water is added to food mixtures – especially those containing flour – the amount of water is very important. Any sort of pastry must have only enough water added to make the mixture manageable. Batter mixtures should be like cream. Cake mixtures are somewhere between the two. The difficulty for people writing recipes is that flour varies in its absorbency. And because flour absorbs water, batter mixtures left to stand will thicken.

Thirdly, water is used as a cooking medium. As well as being cheap, it won’t heat beyond 212ºF. What’s more, when it gets near that temperature it will bubble and steam, so the cook has a constant visual check on the temperature.

AIR

Air expands when it’s heated. Cooks use this fact in many cooking processes in order to get a texture of holes through the food. Pastry would be a concrete slab and steamed puddings solid rubber if it wasn’t for the tiny particles of air that expand to raise the texture. Remember this when handling various types of mixture. Everything must be cold when handling pastry – some cooks chill the dough – so that the cold air will expand more. Pastry must not be carelessly handled, or the air particles will be lost. When stiffly beaten egg-whites are folded into a mixture the word ‘fold’ is used to emphasize the gentle way the bubbles must be handled. Wet mixtures for cakes are beaten like mad to get air into them. Batter mixtures are best if beaten just before cooking.

Self-raising flour has bicarbonate of soda – a raising agent – added to it to produce bubbles. Beating such mixtures can reduce the effectiveness of the raising agent. Yeast does exactly the same (although, because oven heat halts the action of the yeast, the raising takes place in a warm kitchen before the actual cooking).

METHODS OF COOKING

Having dealt with the types of foodstuffs available, let’s turn on the heat.

DRY RADIANT HEAT

Dry radiant heat of open fire, barbecue fire, domestic grill, or broiler. This is the most basic sort of cooking heat there is. It uses open radiant heat (as against the enclosed moister heat of an oven). Although this is a favourite way of cooking meat it is something of an abuse. Only first quality cuts, that will be tender under any circumstances, can be cooked this way. The object is to keep as much moisture and flavour in the meat as possible and to avoid drying the meat right through. For that reason the best things to grill are the things that you like to eat with an undercooked centre, e.g. steak, beef hamburgers, and toasted bread. Things that must be cooked right through, e.g. pork chops, fish, and veal, have to be moved a little farther away from the heat source or they’ll be burned outside before they are completely cooked.

There is an old French saying that a chef is made but a grillardin is born. Grilling requires constant attention because half a minute too long means disaster when the heat is so great. The meat or fish is usually painted with a trace of oil; grilling is especially suited to foods that already contain a lot of fat, e.g. streaky bacon or any oily type of fish.

Since fat shrinks at a faster rate than lean meat it is usual to slash the fat around a piece of steak (see page (#litres_trial_promo)) to prevent the meat curling up. A professional cook taps the meat to test it; meat hardens as it cooks. It’s impossible to give times of cooking because I don’t know how much heat your grill produces nor how far away from it the food is. Always have the grill very hot; light it ten minutes before use if electric or gas. Make sure the grill pan is also very hot. On my grill a half-inch thick steak takes four minutes per side while a steak one-and-a-half inches thick takes more like eight minutes per side. A half poussin takes about thirty-five minutes but is farther away. A one-inch thick fish steak takes five minutes per side and a herring split open takes about five minutes, after which I serve it without turning it over.

SEMI-DRY HEAT

Semi-dry heat of oven. When a piece of meat is two inches thick it’s too big to put under a normal-size grill. In olden days they roasted a whole ox in the open but only by having a vast heat source. Nowadays we use an oven because that encloses the heat around the food and so costs less in fuel and takes up less space. But the enclosed space means that the hot air will become moist, because the water inside the meat is turning to steam. The old open-fire method of cooking – roasting – was so dry that it needed an attendant who would watch the spit turning and constantly moisten the outside of the meat with fat. We still do this when we brush fat over a steak before grilling, because that’s radiant heat, but when a joint (or what Americans call a roast) is put in an oven there is no need to baste it. In fact basting the meat is THE WORST THING YOU CAN DO TO IT. Since there is no need to baste it there is no need to have the meat standing in a tray of highly indigestible burning fat. I will explain why.

All meat shrinks when subjected to heat. Because the meat contains juice, that juice will be forced to the surface by the shrinkage. The juice is vital and everything must be done to preserve it. The hot air of the oven will dry those juices as they emerge and the outside of the meat will become dark and shiny. That first outside slice will be delicious. If you baste the meat you are rinsing those juices away as fast as the heat dries them; stop it. In fact, do the reverse, sprinkle a trace of flour over the raw joint to encourage the juices to dry as they emerge. While the joint is cooking don’t prod the meat, and especially don’t stick a fork into it or a stream of juice will escape.

Fat is an important part of cooking; it should occur naturally in the tissue of the meat but you can put it there by sewing threads – lardons – through it or putting thin sheets of fat around it (pages ref1 (#litres_trial_promo) and ref2 (#litres_trial_promo) illustrate this). Having done that, put the meat on a wire rack so that the heat can get all around it. Put it in the oven. When it is ready, eat it.

When is it ready?

Cooking means bringing the centremost part to a certain temperature. If you have a meat thermometer the sensitive point of it will register this temperature. Leave the thermometer in the joint until the meat is done. If you have a glass-fronted oven you can watch the temperature rise. These are the temperatures I recommend, although the beef and mutton might be a little too underdone for some tastes. Remember though that it’s the underdone meat that contains the most flavourful juices. The temperatures I have given for pork and veal are generally agreed to be the best ones; these meats are never eaten very underdone(i.e. never below 131°F.).

If you don’t have a thermometer then it’s usual to guess the time the meat will take to cook by weighing the joint while considering its general shape, e.g. a thin flat-shaped piece will cook more quickly than a cube shape. As for grilling, only the better quality cuts of beef are suitable for roasting although, because a pig doesn’t get so muscular, any part of a pig can be roasted and very nearly any cut of veal or lamb, if you are careful (i.e. don’t have the oven heat too high). The general temperature for cooking meat is 350–400ºF. because that’s hot enough to ensure the meat doesn’t generate too much steam, but if you have a meat thermometer and like your beef crusty outside and juicy inside you can step up the heat. Cooking inside an oven is called baking. The roast beef of old England is more correctly called the baked beef of old England but the two words have become interchangeable because nowadays no one does true roasting. For some things this semi-dry heat in a box is particularly good, e.g. fish, pastry, bread, and cakes. What’s more, an enclosed box of heat can be measured and controlled.

Many flour mixtures have finished cooking when they become quite dry and so recipes tell you to insert a long needle; if it comes out with a trace of wet mixture on it the cooking isn’t completed. Leave such tests until as near the end of the process as you can. Opening the oven door before the flour has had a chance to harden will result in the tiny particles of heated air that are holding it all up cooling and collapsing: cake sinks.

Thermometers are used only in meat cookery; other items are given the time stated by the recipe plus the skill and experience of the cook. I suggest you make a mark in the margin on the recipe so that next time you will know the exact time that suits your oven. Baked goods are usually allowed to cool on a wire rack so that the steam can escape from all sides and not be trapped and cause sogginess. Meat too will be easier to carve if it is rested – reposé – for ten or fifteen minutes in a warm place, but remember that the cooking process will continue inside the meat even after it’s come out of the oven. Allow for that.* (#litres_trial_promo)

SAUTER

Sauter means to cook in a frying-pan with just enough fat to prevent the food sticking. In a restaurant kitchen the food is turned by tossing it (sauter means to jump); so you see the fat must be minimal. Food to be cooked in this way is usually in thin slices (i.e. slices of veal or calf liver) although sometimes larger things are sautéed for a few minutes to brown them before cooking them in liquid. Onions, carrots, and pieces of meat are often treated like this before they are put in a stew. This is because oil can be heated far beyond the boiling point of water; when we want to extract flavours only available at high temperature this is how it’s done. Fish is often sautéed because its flesh cooks quickly. If the fish has a heavy skin, remove the skin before cooking. If it has a light skin the chef often makes shallow diagonal cuts along the fish to help the heat enter – this is called scotching; it also helps to prevent the fish curling, for all flesh foods shrink when heated and some distort (see also meunière, pages (#litres_trial_promo) and sauté, pages (#litres_trial_promo)).

FRITURE

The word frying – friture – means just one thing in France. It means what we call deep-frying, a technique introduced into Britain and the U.S.A. in comparatively recent times. That’s why in America deep-fried potatoes are called ‘French fries’. The secret of friture is cleanliness of pan and fat and what one expert calls ‘surprise’: the immersing of the item of food in the fat in one fast movement. The fat must always be deep so that the piece of food can float in the fat. The fat must not be old or burnt and if the frying is done correctly there should be no taste of fat in the fried food. The French chef would probably use rendered down beef suet – the fat around the beef kidney – for all kinds of deep-frying (although, of course, he would have a separate pan of it for cooking fish). Vegetable oils are good, especially for sweet items. Mutton fat is never used. Butter burns too easily and is too expensive, and veal fat goes bad too quickly. The technique depends upon the temperature being kept high but never so high that the fat burns. (A thermostat-controlled pan is valuable for deep-frying.) Use a large pan with plenty of fat in it and don’t cram the food in. If you drop a large piece of food into a small pan of fat the temperature will drop. So keep the pieces of food small and of the same size. You must cook the centre before the outside goes dark and overdone.

Since the fat will be well above the boiling point of water any water inside deep-fried food will boil and then turn to steam. For instance, the water inside a potato chip will steam-cook the inside and then bubble up through the fat. This expanding steam keeps the fat at bay; if it didn’t the fat would invade the food and make it greasy and unpleasant. The raw piece of potato must be carefully dried or else so many bubbles of steam will come up that the fat will spill over the side of the pan. Also any water on the potato will be cold; it will lower the temperature of the fat. So the two basic rules are: keep the fat hot and the food dry.

The moisture inside a piece of potato is water, so it doesn’t matter if it escapes into the fat, but the moisture inside meat is juice which will burn if it escapes into the very hot fat. In any case we can’t afford to lose that juice. The answer is to create a barrier that will keep the juice inside. Flour makes a good barrier and if you dip the food (e.g. fish) into milk first it will help the flour cling. This coating is called fariner.

A more complex coating – paner à l’anglaise – is a dip into flour, then beaten egg, and after that tiny breadcrumbs are pressed on to the food. This is often used with fish and liver.