По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

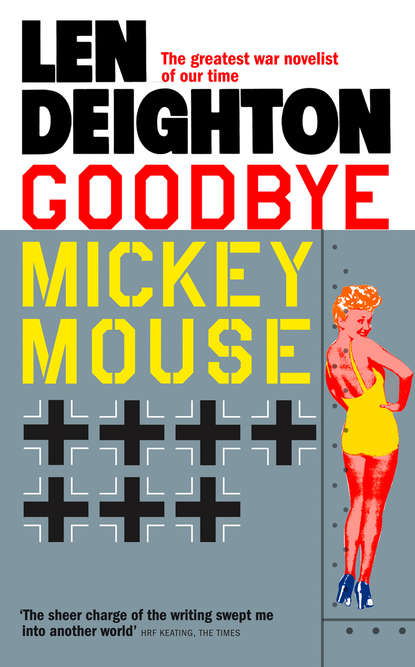

Goodbye Mickey Mouse

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘New machines, new ideas, new commander. I sure hope he’ll get tough with the British. That’s the most urgent thing at present.’

‘The British?’

‘Churchill wants us to fly at night on account of the casualties we’re suffering.’

‘Doesn’t night bombing just mean area bombing—just tossing bombs into the centre of big towns? There’s no industrial plant in town centres, so how could his policy ever end the war?’

‘Night raiding would mean taking more advice and equipment from the RAF. First we take advice from them, then lessons, and eventually we’ll be taking orders.’

‘But Eisenhower’s been appointed Supreme Commander of the Anglo-American invasion forces.’

‘It sounds pally,’ said Bohnen. ‘It sounds like the British are resigned to taking orders from us. But wait until they announce the name of Ike’s deputy, and he’ll be a Britisher. It’s one more step in the British plan to absorb us into RAF Bomber Command. Churchill is using the slogan “round-the-clock bombing” and is suggesting that we coordinate it under one commander. Get the picture? Only one commander for the Army, so only one commander for the Allied bombing force. And who’s the most experienced man for that job? Arthur Harris. If we squawk, the British are going to remind us that Eisenhower’s got the top job. And that’s the way it’s going, the British will get all the powerful executive jobs while reminding us that they’re serving under Eisenhower.’

Jamie was sorting through his vegetables to set aside tiny pieces of onion that he wouldn’t eat. Bohnen remembered him doing the same thing when he was a tiny child; they’d often had words about it. Fastidiously Jamie wiped his mouth on his napkin and took another sip of wine. ‘The British are good at politicking, are they?’

‘They excel at it. Montgomery can pick up his phone and talk with Churchill whenever he feels like it. Bert Harris—chief of RAF Bomber Command—has Churchill over for dinner and shows him picture books of what the RAF have done to Germany. Can you imagine Eaker, Doolittle, or even General Arnold having the chance to chat personally with the President? The way it stands now, Montgomery, via Churchill, has more influence with Roosevelt than our own chiefs of staff have.’ Bohnen drank a little of the Château Margaux and paused long enough to relish the aftertaste. ‘1928 was the great one, but this ’34 Margaux is a close contender. One day I’ll retire and devote the rest of my life to comparing the ’28s and ’29s.’

‘I guess we’ve got to keep hitting strategic targets,’ said Jamie quietly. He hadn’t wanted to get into this high-level argument that his father so obviously relished.

Bohnen shook his head. ‘We’re going after the Luftwaffe, Jamie. There’s no alternative. There’s not much time before we invade the mainland—we have to have undisputed air superiority over those beaches. General Arnold’s New Year orders will make it public record: destroy German planes in the air, on the ground, and while they’re still on the production lines. It’s going to be tough, damned tough.’

‘Don’t worry about me, Dad.’

‘I won’t worry,’ said Bohnen. His son looked so vulnerable he wanted to grab him and hug him as he used to when he was small. He almost reached across the table to take his hand, but fathers don’t do that to their grown-up fighter pilot sons. In some ways mothers are lucky.

Victoria arrived on time, and Bohnen was surprised by the tall, dark confident girl who greeted him. She was obviously well bred, with all those old-fashioned virtues he’d seen in Jamie’s mother so long ago.

‘You have a suite on the river, Colonel. You’re obviously a man of influence.’

‘How I wish I were, Miss Cooper.’

‘Charm, then, Colonel Bohnen.’

‘I’m not even a real colonel, just a dressed-up civilian. I’m a phony, Miss Cooper. Not one of your gilt or electroplated ones either. I’m a phony all the way through.’

She laughed softly. Bohnen had always said that a woman, even more than a man, will reveal everything you need to know about her by her laugh—not just by the things she’ll laugh at, or the time chosen for it, but by the sound. Victoria Cooper laughed beautifully, a gracious but genuine sound that came from the heart rather than from the belly.

‘You look too young to be Jamie’s father,’ she said.

‘Who could argue against a compliment like that?’ said Bohnen.

She went across to the table where Jamie was finishing his meal, and they kissed decorously.

‘Can I order some tea or coffee for you, Miss Cooper?’

‘Please call me Victoria. No, I’ll steal some of Jamie’s wine.’ Jamie watched the two of them; already they seemed to know each other well enough to spar in a way Jamie had never done before.

Bohnen brought another wineglass from his liquor cabinet. ‘Jamie tells me his mother is English,’ said Victoria.

‘Mollie likes to say that. The truth is, she arrived a little earlier than the doctor anticipated and her parents were in England. Tom was setting up a tractor plant near Bradford. Mollie was born in a grand house in Wharfedale, Yorkshire, delivered by the village midwife, so the story goes, with old Tom boiling up kettles of water and only an oil lamp to light the room.’

‘How romantic.’ She looked at Jamie, who smiled.

‘Do you know that part of the world, Victoria?’

‘I’ve passed through it on the train to Scotland.’

‘What a crime,’ said Bohnen. ‘I’ve ridden to hounds there more times than I can count. Marvellous countryside. Do you like horses?’

‘Not awfully,’ she admitted.

‘Well, I knew you had to have one major flaw, Victoria.’ He smiled. ‘Luckily it’s one my son will happily put up with. I remember the first time I put Jamie on a horse. He was very small, and he yelled enough to shake the stables down. The master of foxhounds came running out to see if I was beating the child to death.’ He turned to Jamie. ‘Remember that time at your uncle John’s farm in Virginia?’

‘Airplanes for me,’ said Jamie with some embarrassment.

‘He knows how to avoid questions he doesn’t like,’ said Bohnen. ‘He learned that from his mother.’

Jamie poured a little wine and said nothing.

‘My son has a mind of his own, Victoria. Perhaps you’ve already discovered how stubborn he can be.’ It was said in fun, but there was no mistaking the admonition behind it.

Victoria put a hand out to touch Jamie. His head was lowered but he raised his eyes to her and smiled.

‘Wouldn’t go to Harvard. Instead he went to Stanford.’

‘They let me start a year early,’ Jamie said.

‘And a lot of good that did,’ said Bohnen, smiling to show that he was no longer annoyed by it. He turned to Victoria. ‘He graduated a year early and started his law studies a year early…then he throws it all away to join the Air Force. You could have been practising law by now, Jamie. I could have placed you in the office of some of the smartest lawyers in Washington or New York.’

‘I wanted to join the Air Force.’

‘You would have been a colonel in the Judge Advocate’s corps.’ Getting no response to this he added, ‘But I suppose that wouldn’t be much substitute for flying P-51s over Germany.’

‘No, sir, it would not be.’

‘I have to admire him, Victoria. But he’ll never take my good advice.’ Bohnen laughed as if at his own failings.

‘And how much advice did you take from your father?’ asked Victoria. She had endured the same sort of criticism from her mother, always cloaked in geniality. And so often it was done like this, through a third party.

Her point was not lost on Bohnen. ‘I hope we Americans aren’t too brash for you, Victoria.’

‘My fortune-teller told me I’d meet two dark handsome forceful men.’

‘You don’t believe in fortune-tellers, Victoria? A sensible modern young woman like you?’

‘I believe in what I want to believe in,’ she said with a smile. ‘Surely you understand that?’

‘Exactly the way my analysts treat the strike photos. I understand that all right.’