По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

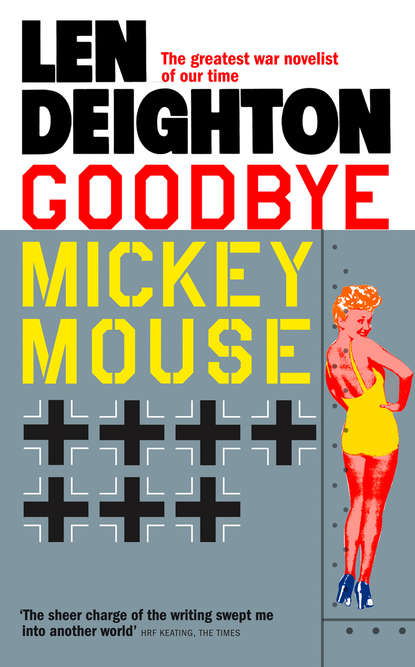

Goodbye Mickey Mouse

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘He tells me he’s met a wonderful girl,’ said Bohnen, ‘and he’s giving me the chance to meet her.’

‘The British trains are all to hell, Alex. Does he have to come far?’

‘I sent a car,’ said Bohnen.

The other man smiled. ‘I’m glad to see you’re not letting the war cramp your style, Alex. Do you think I should get myself a khaki suit?’

‘Running an air force is no different from running a corporation,’ Bohnen told him solemnly. ‘The fact is, running an air force in wartime is easier than running a corporation. As I told my boss, the opportunity to threaten a few vice-presidents with a firing squad would have done wonders for Boeing and Lockheed when they were having their troubles.’

‘You can say that again, Alex!’

‘And what about that damned airline you sank so much good money into? A few executions in that boardroom would have worked wonders.’

‘Military life obviously suits you.’

‘It’s fascinating,’ said Bohnen. ‘And it’s a big job. There are now more US soldiers in these islands than British ones! And our planes outnumber the RAF by about four thousand!’

‘What’s the next step, Alex, Buckingham Palace?’

‘Think big,’ Bohnen said, and laughed.

‘Must go.’ He looked round the room and then back at Bohnen. ‘Who is hosting this feast?’

‘Brett Vance. You know Brett—made a fortune out of cocoa futures just before the war…the big gorilla with glasses, over there in the corner, tearing blooms out of the flower arrangement. No need to overdo the grateful thanks. He just persuaded the Army to put his candy bars on sale at every PX in the European Theatre.’

‘Nice work, Brett Vance!’ said the old man sardonically.

‘Can you imagine how many candy bars those soldiers will consume? Countless divisions of fit young men, hiking and digging and so on, night and day in all kinds of weather.’

‘Does that mean you’re buying stocks in candy bars?’

Bohnen looked shocked. ‘You know me better than that. Let others play the market if they want, but while I’m in the Army there’s no way I could be a party to that kind of thing.’ He saw his companion smiling and wondered if he was being tested.

‘You’re becoming a kind of paragon, Alex. I think maybe I prefer that wheeler-dealer I used to know back home.’

‘I missed the first war. I feel I owe something to Uncle Sam, and I’m going to give this job all I’ve got.’

The older man could think of no response to Bohnen’s passionate declaration. From the other end of the room there was laughter as guests took their leave. ‘Give my love to Jamie. I look forward to hearing your opinion of his girl.’

‘Jamie’s too young to marry,’ said Bohnen.

‘And how about his CO—are you going to let him get married?’

‘Very funny,’ said Bohnen. ‘I suppose you think I interfere too much.’

‘Let the boy live his own life, Alex.’

‘See you next week,’ said Bohnen. ‘You could take a couple of messages for people in Washington.’

‘Go easy on the boy, Alex. Jamie doesn’t have that hard cutting edge that we grew back in 1929.’

‘He’ll get no preferred treatment. He’s a soldier, and this is war.’

‘It’s serious, Dad. We’re in love.’ He found it difficult to talk to his father after so many years apart.

‘And when exactly do I get a chance to meet the young lady?’ Colonel Bohnen consulted his watch.

‘Three fifteen. She thought we’d like to have some time together. She’s downstairs right now, having lunch with her aunt.’

‘That’s most considerate of her,’ Bohnen said, and wondered whether it was intended as an opportunity for Jamie to get his blessing for an intended marriage.

‘You’ll like her, Dad. It was her idea that I phone you.’

How like Mollie the boy looked, the same mouth and same wide-open earnest eyes and the same nervous manner, as if he expected Alex Bohnen to bite his head off. What did the boy expect—a paternal chat about the unhappiness that can follow a hasty marriage? Or the senior officer lecture about the socio-medical consequences of casual relationships? He would get neither. ‘Sure, I’m going to like her,’ said Bohnen, pouring more of the Château Margaux. ‘Eat the lamb chops before your meal gets cold.’ Jamie had let his father choose the food and wine, knowing how much pleasure that would give him. He was right; Bohnen had been through the room-service menu with meticulous care and questioned the waiter at length about the temperature of the wine and the locality in which the lamb had been reared.

‘It’s a fine meal,’ said Jamie.

‘It’s better to have it served up here in my suite. I would have eaten with you but I had an official lunch.’

‘It’s a fine claret too.’ Bohnen noted his son’s Britishism and wondered if he’d been tutored by old Tom Washbrook, who kept a legendary table, or by his no-good brother-in-law who was drinking away the profits of the bar and grill he owned in Perth Amboy.

‘The Savoy cellars go on forever. This is the finest hotel in the world, Jamie. And the management know me from way back before the war.’

‘1934,’ said Jamie, turning the bottle to examine the label. ‘So you’re still very busy?’

‘We’re in the middle of the biggest expansion programme in history, and now Doolittle has arrived to take over from General Eaker.’

‘What’s the story behind that one?’

‘Go back to last October and read about the Schweinfurt raid, the way I’ve been doing to prepare a confidential report. It was a long ride through clear skies, our bombers punished all the way there and all the way back again. No escorting fighters, and the Germans had plenty of time to land and refuel before slaughtering more of our boys. Twenty-eight bombers were lost on the outward leg, and by the time formations reached the target, thirty-four had turned back with battle damage or mechanical failure. The return trip was even worse!’

‘I’m listening, Dad.’

Bohnen looked at his son. He didn’t want to frighten him, but he knew that a son of his would not be readily frightened. ‘If the truth of it ever gets out, Congress will tear the high command to pieces. Any chance of America getting a separate air force will have gone for good. Even now we’re not publishing the whole truth. We don’t tell anyone about our ships that crash into the ocean on the way back, or the ones that land with dead and injured crew. We don’t say that for every three men wounded in battle there are four crewmen hospitalized with frostbite. And we don’t tell anyone how many bombers are junked because they’re beyond economical repair. We don’t talk about the men who would rather face a court martial than go back into combat, or about the psychiatric cases we dope up and send home. We don’t let reporters go to the bases where we’re having trouble with morale, or admit to the decisions we’ve had to make about not sending unescorted formations back to those tough targets again.’

‘It sounds bad.’

‘We never released the true Schweinfurt story and my guess is we never will.’

‘With the Mustangs we’ll escort them all the way.’ Jamie had forgotten how intense his father always became about his work. He wished he could see him relax, but he never did.

‘I spent last month pleading for long-range gas tanks. We’re using British compressed-paper ones, we can’t get enough. Then on Friday I got a long report from Washington telling me it’s impossible to make drop tanks from paper. That’s what we’re up against, Jamie, the bureaucratic mind.’

‘The Mustang is the most beautiful ship I ever flew.’

‘And everyone knew it last year except the “experts” at Materiel Division who seemed to resent the fact that she needed a British-designed engine to make her into a real winner. The Air Force lost months due to those arguments, and all the time the bomber crews paid in blood.’

‘Will things be better under Doolittle?’