По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

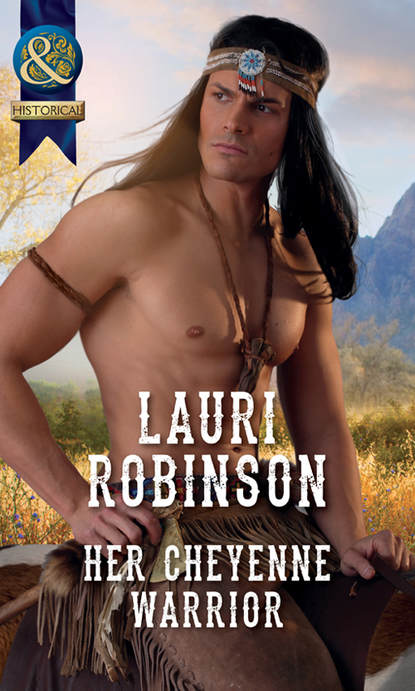

Her Cheyenne Warrior

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“You sit,” Little One said.

The woman did so, without glancing his way. “What’s your name?” she asked.

“Ayashe, Little One. What they call you?”

“Lorna, my name is Lorna Bradford. Where are my friends? Where are our wagons?”

Although not necessary, the routine was for Ayashe to translate everything said into Cheyenne, and she did so.

Black Horse pondered the woman’s name for a moment, and wished he could say it aloud, for it sounded odd in his head. He responded by saying her friends and wagons were safe, and waited for that to be translated by Little One.

“Safe? Where? Where are they?”

Little One repeated what the woman had said, and then told the white woman that he had questions he wanted her to answer.

“I won’t tell him anything until I’m told where my friends are,” the woman responded, giving him a solid glare.

Black Horse held his response until Little One repeated the command. He lifted a brow and shook his head. Once again in Cheyenne, he said, “Tell her she is in no position to demand things.”

Upon hearing his words translated, the woman crossed her arms and glared harder.

He lifted his chin just as bold and defiant, silently telling her he could sit here as long as she could. Longer. They would not break camp to follow the buffalo until a scouting party returned with news that they had found the main herd. Only stragglers had been spotted so far, but the Sun Dance had been performed. The sacred buffalo skull, stuffed with grass to assure plenty of vegetation for the buffalo and therefore plenty of buffalo for the people, sat near the sun pole in the center of the village, rejuvenating its soul to call out to the great herds. The herds would soon arrive. Sweet Medicine never failed.

His thoughts returned to the white woman. The idea of her in his lodge when darkness arrived stirred his blood. Turning to Little One, he said, “Tell her once she answers my questions, you will take her to her friends.”

Little One was still speaking when Lorna started shaking her head. “No, tell him to bring them here, to his tent, or teepee, or whatever you call it. Once I see they are unhurt, I’ll answer his questions.”

Black Horse bit the tip of his tongue. Unhurt? Who did she think they were? The Comanche? While Little One repeated what the woman had said, Black Horse kept his stare leveled on Poeso—a much more fitting name than Lorna. If he had called one of the other women into his lodge in the first place, he would already have his answers.

Never shifting his gaze, he told Little One to find a camp crier to run and tell the warrior families to bring the other women to his lodge.

Without question, Little One rose.

Poeso grabbed Little One’s arm. “Where are you going?” Fear once again clouded her blue eyes when she turned on him. “Where are you sending her?”

Although her fear did not please him, Black Horse offered no answer. Neither did Little One as she broke free and slipped out of the lodge. Poeso started to rise, but he grabbed her arm, forcing her to stay put.

“Let go of me, you brute,” she whispered.

The fear flashing in her eyes turned his stomach cold. She tried to twist from his hold; and though he considered letting her go, he knew she would run if he did. For a brief second, he considered telling her—in her language—that she was in no danger, but chose against it. Little One would return soon.

“You are nothing but a beast, a heathen,” she said between her teeth, hissing like a cat. “And I want my gun back.”

The thought of her little gun made him grin.

“You think that’s funny? You think it’s funny to abuse a woman?”

He was far from abusing her. If she calmed her temper she would know that. He rather liked her hissing and snapping. It made her eyes sparkle and her cheeks turn red. Furthermore, few women dared speak to him so. None. Not in a very long time. Hopping Rabbit used to snap at him when they were married. He had given her the name Hopping Rabbit then, after she’d become his wife, because of how she used to hop about the lodge.

Holding his breath, he waited for the pain that appeared in his chest whenever he thought of his dead wife to build, and then let it go as he blew out the air. It had been two winters and two summers since she had died. Their baby, still inside her, had died, too. That was the way. Death was part of the continuation of life. Everything came from and went back to the earth to rebirth another time, but the end of one life had never hurt him like Hopping Rabbit’s. He never blamed himself for the death of someone as he did his wife and child. Because he had killed them.

A white man at the fort, not a soldier, but one who trades many things, had said Hopping Rabbit would like the white material. It was tiny and soft and had flowers sewn on it. Little One had called it a handkerchief, and Hopping Rabbit had liked it. She held it to her nose, drawing in its smell and smiling. For two days. On the third she became ill. On the fifth, she died. One Who Heals said it was the white man’s sickness. That her medicine could not stop the white man’s poison.

“I know you can hear me. You might not understand my words, but you can hear me.”

Black Horse sighed as his attention returned to the white woman. The Shoshone, miles and miles away, could probably hear her. He did not need that. Did not need his or any band believing he was befriending the white man.

“Where did you go?” she asked as Little One entered the lodge. “What did you do?”

Little One smiled as she sat down, but said nothing. Pride filled him. She was more Cheyenne than white.

“What? You can only speak when he tells you?” Poeso asked. “Speak only when spoken to? You can’t live your life like that. You have to stand up for yourself. Speak your own mind. If you give a man an inch, they’ll take a mile. Don’t let this beast rule you. You—”

“My brother is not a beast,” Little One said sharply.

Black Horse’s stomach flipped. Little One could be as snippy as this white woman when the need occurred. A trait all white women must possess. He should have called One Who Heals into his lodge. Perhaps her great medicine would work on Poeso.

“And I speak whenever I want,” Little One continued. “When I have something to say.”

The white woman looked startled, and snapped her lips closed as noises sounded outside the tent. Her gaze shot to him. He told Little One to open the doorway so she could see her friends.

Little One nodded and rose, and then said, “You stay. Just look.”

As soon as the flap was pulled back, Poeso shouted, “Meg, Betty, Tillie, are you all right?”

“We’re fine, are you?”

“Yes, I’ll be out in a minute.”

Black Horse waved a hand, and Little One let the flap fall back into place and returned to sit beside him. It took a moment for him to remember what information he wanted from this woman. The wind that had entered his lodge had filled the air with Poeso’s scent, and that had stirred a longing in him. “Ask her who those men were at the river.”

Little One did so, and “Hoodlums” was Lorna’s answer.

That much he knew, but waited for Little One to translate it into bad men. “What did they want?”

She sat quiet for a moment after Little One repeated his question, and glanced toward the flap covering the entrance of his lodge. “Ever since Betty’s husband died, Jacob Lerber, the leader of that group of men, had been watching her, waiting to catch her alone. We were all part of the same wagon train, until Tillie became ill after her husband died. That’s when Meg and Betty and I took her and left the wagon train. She needed a doctor. We found one, and as soon as she was better we continued on. We are on our way to California. We don’t have anything of value. Just the supplies we need. There is no reason to keep us here. We won’t tell anyone where your camp is, if that’s what he’s afraid of. In truth, we hope we don’t see anyone along the way. Four women traveling alone might look like an easy target, but we aren’t. We have weapons.”

Black Horse found himself biting his lips together to keep from grinning at how she contradicted herself, and at her mention of weapons. A tiny pistol and old rifle were not weapons. He noted something else while she spoke. Her voice was like that of the people from across the great waters. His father called it England. Where many of the white men come from. Long ago they crossed the great water to take land away from various Indian tribes. They broke promises and angered many. Several tribes, including the Southern Cheyenne along with their Arapaho allies raided unprotected settlements and wagon trains. The retribution of that was still to come. Black Horse had envisioned that would happen when the white men stopped their war against each other. One Who Heals had confirmed it.

Little One told him, “I’m not repeating all that.”

Black Horse nodded and gave himself time to settle his roaming thoughts. The white men fighting each other was good for the tribes. The more men killed, the fewer the Indians needed to battle. Peace and harmony had been the way of Tsitsistas for many generations, long before they had to start following the buffalo to feed their families. He strived for that kind of peace, the kind his father’s father had told stories about. Such harmony could not be found with mistrust living between the bands and the white man. Too many tricks had been played by the white man’s gifts and words. Just as the white trader had tricked him with the poison in the gift he had brought home to Hopping Rabbit, others had been tricked, and others had died. Their poison took many shapes and arrived in many ways. This did not make him hate all white men or seek to harm them. That would spoil his blood, and that of his tribe. A leader could not do that, but he listened carefully to his insides when it came to trusting anyone.

“Did you tell him what I said?” Poeso asked.

“Yes,” Little One answered.

“It didn’t sound like it.”