По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

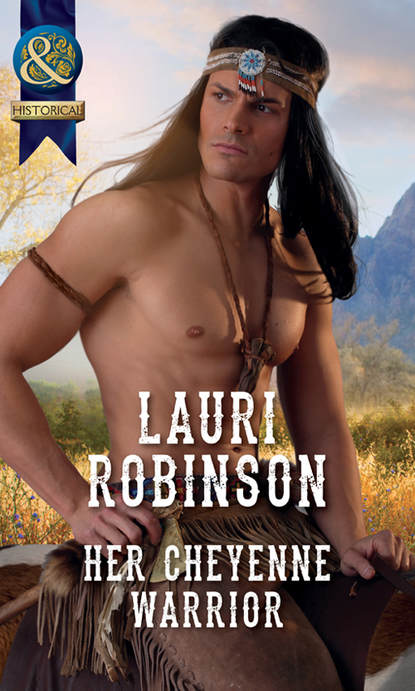

Her Cheyenne Warrior

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Meg had told her that, but Lorna hadn’t believed it. Whether she acted like it or not, Meg wasn’t old enough to have gone all the way to California and back to Missouri. At least that was what Lorna had believed up until now. Meg did seem to know a lot about a variety of things they’d needed to know along the way, including Indians, it appeared, but she had figured Meg had learned most of it from reading about it. Just as she had. She’d also hoped they wouldn’t encounter any Indians. None.

Flustered, Lorna said, “He’s not a chief. He doesn’t have a single feather in his hair.” Or clothes on his body, other than a pair of hide britches and moccasins. She chose not to mention that. The others had to have noticed.

“They don’t wear war bonnets all the time,” Meg said. “White people portray that in paintings and books because it makes the Indians look fiercer.”

Lorna glanced at the brave sitting on the back of the wagon. “No, it doesn’t.” If you asked her, a few white feathers among all that black hair might make them look more human. Not that humans had feathers, but wearing nothing other than hide breeches and moccasins, these men looked more like animals than humans. Especially the beast who’d plucked her out of the water. The one who’d stolen her gun. She would get that back. Soon.

She was where she was because of a man, and another, no matter what color his skin might happen to be, was not going to be the reason her life changed again. Was not! She’d fight to the death this time. To the very death.

“Give me those,” she snapped while snatching her clothes from beneath the feet of the brave who sat on the tailgate. It was difficult with the wagon rambling along at a speed it had never gone before, and with the others crowded around her, but Lorna managed to get dressed—minus the habit—and put on her boots.

She then scrambled past Meg and over the trunks until she stuck her head out of the front opening. The brave was too busy trying to control the mules to do much else. Lorna climbed over the back of the seat—despite how Meg tugged on her skirt—and sat down next to him. The other wagon was following them at the same speed. The braves surrounding them had their horses at a gallop, too. The mules would give out long before their horses would; even she could see that.

Whether he was a chief or not, the man on the black horse was a fool to force the animals to continue at this speed. She needed these mules to get her to California.

“What’s his name?” she asked, pointing toward the leader of the band. The one atop the finest horseflesh she’d seen since coming to America. If she had an animal like that, she could have ridden all the way to California, and been there long before now.

The brave hadn’t even glanced her way.

“What do you call him? That one on the black horse?”

The brave didn’t respond.

“Him,” she repeated, “on that black horse, what is his name?”

The brave grunted and slapped the reins across the backs of the mules again.

Lorna let out a grunt, too, before she cupped her hands around her mouth. “Hey, you on the black horse!” When he glanced over one shoulder, she added, “You better slow down! Mules can’t run like horses!”

He turned back, his long hair flying in the wind just like his horse’s mane. The two of them, man and horse, appeared to be one, their movements were so in tune.

“Did you hear me?” she asked.

“Everyone heard you,” Meg said from inside the wagon. “Hush up before you irritate him.”

“I don’t care if I irritate him,” Lorna answered. “He’s already irritated me.”

“He saved us from Lerber.” That was Betty. “They all did. Shouldn’t we be thankful for that? Show a little appreciation?”

Lorna spun around to let the other woman know her thoughts on that. Words weren’t needed. Betty cowered and scooted farther back in the wagon.

“My guess,” Meg said, “is that is Black Horse. He’s the leader of a band of Northern Cheyenne.”

Lorna shot her gaze to Meg. “How do you know that?” The name certainly fit the man.

“I’m just guessing,” Meg said. “They’ll slow down after we cross the river. They are putting distance between us and Lerber.”

“Distance? Why?” Lorna asked. “They killed Lerber.”

“No, they didn’t. I told you they are Cheyenne. They just stole their horses.”

“You can’t be sure of that.” Lorna certainly wasn’t.

“They are the reason I said we had to take the northern route,” Meg said. “The Indians are friendlier. Southern Indians, even bands of Cheyenne, are the ones that kill and kidnap people off wagon trains. They use them as slaves.”

Lorna had assumed Indians were all the same, no matter what band they were. “How can you possibly know that?”

Meg chewed on her bottom lip as if contemplating. After closing her eyes, she sighed. “My father was a wagon master. He led a total of eight trains to California. Two of them, I was with him.”

Lorna hadn’t pressed to know about a family Meg never mentioned. “Where is he now?”

“Dead.”

The word was said with such finality Lorna wouldn’t have pushed further, even if she hadn’t seen the tears Meg swiped at as she sat down and looked the other way.

Lorna swiveled and grabbed the edge of the wagon seat. The horses and riders ahead of them veered left and the wagons followed, slowing their speed as they grew nearer to the trees lining the river. A pathway she’d never have believed wide enough for the wagon, let alone even have noticed, widened and led them down to the river. The brave handled the mules with far more skill than she’d have imagined, or than she had herself. As long as she was being honest with herself she might as well admit it. With little more than a tug on the reins and a high-pitched yelp, he had the mules entering the river. The water was shallow. Even in the middle, the deepest point, it didn’t pass the wheel hubs.

In no time they’d crossed the river and traveled into the trees lining the bank on the other side. Just as Meg had suggested, their pace slowed and remained so as they made their way through a considerable expanse of trees and brush. The trail was only as wide as the wagon, and once again, Lorna sensed that you had to know this trail existed in order to find it. She did have to admit the shade was a substantial relief from the blazing sun they’d traveled under for the past several weeks. She’d take it back though, the heat of the sun that was, to regain her freedom from this heathen as big as the black horse he rode upon.

He hadn’t turned around, not once, to check to see if they’d made it across the river or not, but she’d rarely taken her eyes off him.

“Where are you taking us?” she asked the brave beside her.

A frown wrinkled his forehead, which didn’t surprise her. English was as foreign to him as their language was to her. Turning toward Meg, she asked, “Where are they taking us?”

“Their village would be my guess,” Meg said.

“Why?”

“I haven’t figured that out yet.”

“I have,” Lorna said. “To kill us, right after they rape us.”

“No, they won’t,” Meg insisted. “But that is what Lerber would have done.”

Lorna didn’t doubt Meg was right about Lerber, nor did she doubt that this band of heathens would do the same. Despite Meg’s claims. She’d read about the American Indians, in periodicals from both England and New York. Anger rose inside her. If only the railroad went all the way to the West Coast she would have been riding in a comfortable railcar, like the one she’d traveled in from New York to Missouri. There had been heavy velvet curtains to block out the sun and a real bed. Tension stiffened her neck. Getting to California was worth sleeping on the hard ground, and no one, not even a band of killer Indians was going to stop her from getting there.

“Look at that.”

Lorna turned at Tillie’s hushed exclamation. As the wagon rolled out of the trees, a valley of green grass spread out before them, with a winding stream running through the center of it. Teepees that looked exactly like ones in the books she’d read were set up on both sides of the stream, hundreds of them. The scent of wood smoke filled the air and a group was running out to meet them on the trail. It wasn’t until they grew closer that she realized the group was mainly children and dogs. Some of the dogs were as tall as the children they ran beside, others tiny enough to run through the children’s legs, and many of them were decorated with feathers and paint. She’d read about Indians doing such things to their horses, but not their dogs.

What strange creatures they were, these Indians, and for a brief moment, she wondered what her mother would think of this peculiar sight. Mother hated America, which was partially why Lorna had chosen to return here. Maybe these creatures were part of the reason her mother hated her father’s homeland so severely.

Lorna had told herself she’d love America, if for no other reason than to spite her mother, but painted dogs were hard to ignore. As hard to ignore as the man on the black horse.

Most of the children now ran a circle around him, yipping and clapping. The last trek of their journey he’d led them at a pace the mules were much more accustomed to—slow, miserably slow. As their train rumbled forward, the smaller children and their dogs headed back toward the camp, whooping and yelling in their language. It sounded ugly and harsh, especially when shouted at such a volume. A few of the group, older boys it appeared, ventured all the way to the wagons, where they chattered among themselves and pointed at her sitting on the seat as if she were a circus attraction.

Usually, children and their innocent tactics humored her, but these, as scantily dressed as the big man on the black horse, were alarming. She waved a hand to shoo them away, but they laughed and continued walking alongside the wagon. Shouting, telling them to be gone did little more than make them laugh harder, and mimic her.