По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

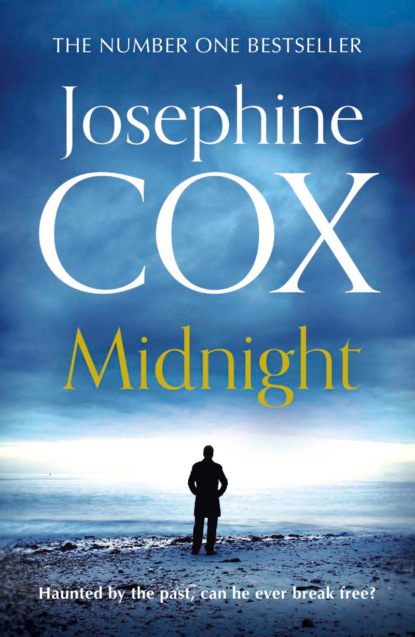

Josephine Cox 3-Book Collection 1: Midnight, Blood Brothers, Songbird

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Yes?’

‘Why did you seek my help?’ Reaching across the desk, the psychiatrist switched on the recording machine.

Feeling safe in this man’s calming presence, Jack told him, ‘I have these nightmares. I’ve always had them. They frighten me.’

‘Are the nightmares always the same?’

‘Always. Sometimes in the day, I can’t get them out of my head. Other times, I make myself shut them out. If I didn’t, I wouldn’t be able to think. I wouldn’t be able to do my work.’ He paused, a feeling of dread creeping over him like a dark, suffocating cloud. He continued in a low voice, ‘Sometimes, I think they might drive me crazy.’

‘You say you’ve had them for as long as you can remember?’

‘Yes.’

‘Can you recall exactly when they started?’

‘No.’

‘When you were at school, did you have them then?’ He was trying to pinpoint the age at which Jack’s nightmares began.

Jack’s breathing quickened. He would never forget the awful times at school, when he was afraid of everything and everyone. Sometimes, when the other children were pointing at him and whispering behind his back, he hid in the toilets.

‘Jack?’

Jack wasn’t listening. The memories and the images were too strong. He felt himself being drawn back. There were no voices here. Only the silence, and . . . something else, something bad. He knew it was there, but he didn’t know what it was.

‘Jack, can you hear me?’ Mr Howard was aware that Jack was sinking deep into the past, but that was a good thing. Glancing at Dr Lennox, who was content just to listen and learn, he gave a little nod, as though to reassure him that everything was going well.

When Lennox acknowledged this with a discreet smile, Howard returned his full attention to Jack.

‘Are you ready to talk with me, Jack?’

‘Yes.’

‘Did you tell your teachers about the dreams?’

There was a tense moment, and then Jack’s voice, firm and decisive: ‘No! I never told them anything.’ He remembered something, though. ‘Once, when we had a drawing lesson, I made a picture of my nightmare. The teacher was angry with me. She made me stand up in class, while she showed my picture to the other children. She said my picture was nonsense, that I had not been listening to her, and that I would have to stay behind and draw another picture – one that made sense. The other children teased me about that – but not Libby. She was my friend.

‘Jack?’

‘Yes?’

‘What else did your teacher say about the drawing?’

‘She said I had bad things in my head. She tore the drawing up, and the children laughed at me.’

‘So . . . the teacher asked you to draw a particular thing, and you drew your nightmare instead. Why did you do that, Jack? Were you really asking for her help, do you think?’

‘I wanted her to see, that’s all. But she called my mother in and made a big fuss.’ As he went deeper into the past, Jack’s voice became more childlike.

‘In what way did she make a fuss?’

‘She said the drawing was disturbing, and that I was disobedient.’ He gave a knowing smile. ‘I think my drawing frightened her.’

‘And what did your mother say?’

‘She said I ought to listen to the teacher in future, and not draw rubbish stuff.’

‘Did you ever draw like that again, either at school or at home?’

‘Never!’

‘So, what else did your mother say . . . about the drawing you did, and why the teacher was so very angry?’

‘When we got home, she kept asking me what the drawing was. When I said I didn’t know, she got into a rage, yelling and screaming, demanding to know what it was that I’d drawn, why I had drawn it, and if it really was like the teacher said. She demanded to know where I had seen such a place as the teacher described. She said I’d better get these bad things out of my head, or they might have to put me in a home.’

‘Did she tell your father?’

‘I think so, ’cause later on I had to see the school psychologist. But I never told him the truth.’

‘Did you ever talk to anyone else about the nightmares?’

‘Only Libby, just once. She said I should just forget about it, that it wasn’t real.’

‘Was that a hard thing to do, Jack? Keeping it to yourself?’

‘Very hard, yes.’

‘Tell me about Libby.’

‘She lived near us on Bower Street.’ Jack’s face broke into a smile. ‘She was very pretty, and she was good-natured. All the boys liked her but she wasn’t interested in them. She preferred to hang out with me. She was a tomboy. I think that’s why everyone liked her. She could play football, and run like the wind. She climbed trees and swung from the branches, like a monkey.’

He gave a small chuckle, ‘Libby was fun. She made me laugh. Sometimes, she even made me forget the bad things.’

‘But you never again spoke to her about the bad things?’

‘She didn’t want me to.’

‘And you never told anyone else?’

‘Never!’

‘Was that because you thought they wouldn’t believe you?’

‘I didn’t want the other kids to think I was weird.’

Mr Howard opened the top drawer of the desk, from where he collected a larger writing-pad.

‘You’re doing very, very well, Jack,’ he said, his voice warm and encouraging. ‘Now, just let yourself go back, to when you were inside the dream. My voice will go with you. I’ll be with you, every step of the way . . . Now, Jack, I want you to tell me how you feel . . . what you see. Describe the scene Jack.’