По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

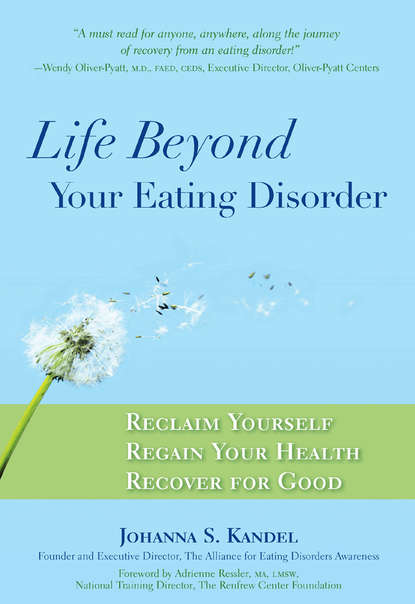

Life Beyond Your Eating Disorder

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

When I returned from camp at the end of the summer, I entered a new school for the performing and visual arts that had just been established. I had academic classes in the morning and dance classes in the afternoon. Then, when school was over, my mother picked me up and drove me and my friends to the dance academy of the local professional ballet company, where I was also taking classes. That fall the artistic director and the ballet mistress of the company came to our class and told us that they would be holding auditions and choosing a number of students to appear in that season’s production of The Nutcracker. They said that they were giving us this heads-up because they hoped that we’d work on our technique and also lose a bit of weight before the auditions took place. I wanted to be chosen so badly that if they’d told me to go upstairs and jump off the roof to get the part, I would have done it. But beyond simply wanting the part, I was already, even then, the quintessential people pleaser. Because of my father’s high expectations of me, as well as those I placed on myself, I simply didn’t believe, however well I did, that I was good enough. As a consequence, I believed that if I did enough to please other people, they would like me, and I also believed that if other people liked me, I would find it easier to like myself. Therefore, my incentive to lose that weight was twofold: to get the part and also to please the ballet mistress and artistic director of the company.

If I wanted to achieve my dream, I would have to be thin. If I was going to do something—whatever it was—I needed to do it perfectly.

I was still small and prepubescent. I had no idea how to lose weight, but I was determined to do it. At that time, in 1990, fat-free was all the rage, so I decided that the thing to do would be to cut as much fat as possible out of my diet. I remember telling my mother that I was going on a healthy-food diet and would be eating fruits, vegetables and lean meats. (You know, this is something I must have read somewhere—probably in one of those magazines that teach you five ways to lose weight without really trying. Certainly, as a twelve-year-old, it wasn’t anything I had come up with all by myself!) My mother, of course, thought that would be great. What parent wouldn’t be happy to hear that her child wanted to eat lots of fruits and vegetables? I bought a fat-and calorie-counter book and began to look up the content of absolutely everything I ate.

They hoped that we’d work on our technique and also lose a bit of weight before the auditions took place.

I don’t actually know if I lost any weight on my “healthy” diet, but I auditioned, and out of the fifteen girls in my class I was the only one not chosen for a part. The people from the ballet company took me aside and told me that the reason I hadn’t been cast was not that I wasn’t good enough, but rather that I looked so young. I was, in fact, one of the smallest and youngest in my class, but despite what they said, I believed they really meant that I was too fat and they were just trying to be kind. At that point I made a pact with myself: no matter what it took, I was going to get a part the following year.

I became very strict and rigid with my diet. I started to exercise even more, and I did lose some weight. People noticed very quickly, and they were telling me how good I looked, which made me feel great. But it also convinced me that I must have been really big. If not, after all, why would they be making such a big deal over the weight I’d lost?

Despite what they said, I believed they really meant that I was too fat.

Some time near the end of my seventh-grade year, our health teacher showed a made-for-television movie about a young gymnast who was battling an eating disorder. I think that most of my classmates watched the girl in that movie and thought, What is she doing? That’s terrible! But I looked at it and thought, Hey, I can do that for a while. I’ll just get down to my goal weight and then I’ll stop. I still thought losing weight was all about control, and since I was losing weight, I felt as if I were in control. Once I’d started, I just couldn’t stop. My eating disorder took control of me. In retrospect, the danger of those movies (and we’ve all seen them) is that they provide anyone who’s predisposed to developing an eating disorder with step-by-step instructions for how to do it really well.

Have you ever had a really bad stomach flu and had people tell you afterward how great you look because you’ve lost a few pounds? You might want to say, “Are you nuts? I was sick as a dog.” But you might also get the idea that if you stuck with a restrictive diet awhile longer, you’d look even better. That was more or less how it went for me. I cut back more and more on my food intake, and the response I got from other people was, “Wow, Johanna, I wish I had your willpower. You can just sit there with a piece of cake in front of you and not eat it.” Meanwhile, I was dying on the inside. People seem to think that anyone with an eating disorder simply isn’t hungry or is indifferent to food, but that’s the furthest thing from the truth. I thought about food all the time. My life revolved around what I was or wasn’t eating, how much I was exercising and all the negative thoughts that constantly played like an endless tape loop in my head: I’m not good enough. I’m not smart enough. I’m not thin enough. Nobody’s going to like me. Every day I was able to fight off the hunger, I felt I’d won—even though the only person I was at war with was myself.

I was dying on the inside. My life revolved around what I was or wasn’t eating, how much I was exercising and all the negative thoughts that played like an endless tape loop in my head.

By the time I entered ninth grade, however, I stopped getting positive feedback for losing weight. The remarks of my teachers and classmates began to change. People started to ask me if I was all right. And to tell me that I looked really tired. I was already exhibiting various symptoms of anorexia—the paleness, the circles under my eyes, the sunken cheeks, the tiredness. I was tired all the time, but I still had the mental strength to get up, go to school, dance eight hours every day and maintain straight As. I was truly running on empty, but for the first time in my life I felt that I was really good at something; my eating disorder was rewarding my perfectionism. Even though it was the furthest thing from the truth, I believed that I was in complete control. In addition, because so much of my limited energy was focused on my eating disorder, I didn’t have any energy left to think about anything else. I was emotionally numb, and I liked that because I no longer had to worry about whether or not I was good enough for my parents, for the world or for me.

Every day I was able to fight off the hunger, I felt I’d won—even though the only person I was at war with was myself.

Tenth grade was probably the height of my anorexia. I’d re-auditioned for several parts in The Nutcracker and gotten every role I tried out for, but now even my ballet instructor was very worried and started to express her concern about my weight. I still remember the day she took me aside and told me I’d lost too much weight. I felt so anxious and so guilty that I went home and had my first binge episode. I just wanted that feeling of anxiety to go away, and bingeing allowed me to stuff down the uncertainty and apprehension, at least for the moment. But almost immediately after, I would again be overwhelmed with guilt. Still, the anorexia continued throughout my junior and senior years of high school. I even passed out a few times—luckily never while I was driving.

I believed that I was in complete control.

Everything came to a head one evening in my senior year, when I had flown to New York to audition for a ballet company. When I got back home, still wearing my ballet tights under my jeans, I went into the bathroom to change. I’d always been very careful not to let people see my body, because I was so ashamed and uncomfortable in my own skin. When I looked in the mirror what I saw, although I didn’t realize it at the time, was a distorted image of myself. If you’ve ever looked in one of those fun-house mirrors that makes you look extremely distorted, you’ll know what I saw when I looked at my reflection. The only difference is that when you’re in the fun house, it’s the mirror that’s doing the distorting, but for me it was what my brain thought it saw. I wore layers of baggy clothes and always made sure to change in the bathroom with the door closed. On this particular evening, however, the door was apparently not completely shut, and just as I was taking off my dance clothes with my back to the door my mother happened to walk around the corner and glimpse for the first time in almost six years what I had been so careful to hide. When she saw me, she started to cry. She began shaking me and screaming, “What are you doing? You’re killing yourself!”

I no longer had to worry about whether or not I was good enough for my parents, for the world or for me.

Whenever I tell my story, people want to know, “What about your parents? Didn’t they notice anything?” I admit that I sometimes wondered that myself; however, by that time I was driving myself to ballet class, and if my mother ever did see me in performance, I was on a stage, wearing a tutu and tights, with makeup on and my hair in a ballet bun. In other words, I was no longer Johanna. And the truth is that many people did know what was going on. I know now that several of my teachers had noticed my weight loss and expressed their concern to one another. And my best friends admitted later that they had been very worried but had been afraid to confront me because they thought I’d be angry and that would be the end of our friendship. In fact, while everyone knew I had a problem, no one quite knew what to do about it.

I’d always been very careful not to let people see my body, because I was so ashamed and uncomfortable in my own skin.

In addition, I’d become extremely manipulative and careful about keeping my secret from my parents, because I knew they were the only ones who could force me into treatment—and the last thing I wanted to do was let go of the eating disorder. It was my best friend and yet my worst enemy; it was what I knew and what I could count on. It was safe and, although very dangerous, very comfortable. I knew what it was like to have an eating disorder; I didn’t know what it was like to recover—and what is known always feels safer than what is unknown. If there was a message on our answering machine from a friend’s parent, I erased it before they got home. If my guidance counselor asked what I’d eaten that day, I’d come up with a whole list I could rattle off so convincingly that I sometimes got angry with myself for eating things I actually hadn’t eaten. The truth was that my parents didn’t really have any reason to think there was anything wrong. My mother had come from a family where every bite of food was cherished, and she’d been very thin as a young woman, so the idea that I would purposely starve myself was a completely foreign notion to her. In addition, I was dancing six to eight hours a day, so it would stand to reason that I was thin, and whenever I ate with my parents I managed to manipulate my food and make it appear as if I were eating. For people who don’t have an eating disorder, all this may be hard to imagine, but if you have or have had an eating disorder, I’m sure you know exactly what I’m talking about. Those of us with eating disorders become experts at keeping our secrets.

When my mother saw me, she started to cry. She began shaking me and screaming, “What are you doing? You’re killing yourself!”

In any case, that evening in the bathroom, my mother couldn’t help seeing what I’d been hiding, and all I could do was to keep reassuring her that everything was okay, I was in control and I knew what I was doing. Still, she insisted that I see a doctor, and she went with me. To my amazement, when I got on the scale he looked at my weight and said, “You’re really thin, but you’re okay.” Then he looked at my mother and said, “Just give her some of your good French cooking.” This was 1996. Anorexia and bulimia were no longer secrets. They were listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; people knew about the death of Karen Carpenter; Tracey Gold had gone public about her battle with an eating disorder; and the seminal movie about anorexia, The Best Little Girl in the World, had aired on network television more than ten years before. But then, as now, there were many health-care providers who hadn’t been properly educated about how to diagnose or treat eating disorders. And, of course, when a parent hears from a doctor whom she trusts that her child is okay, her inclination is to be relieved and accept the diagnosis.

So I’d dodged that bullet, at least for the moment. But about a month later my mother noticed that I wasn’t getting any better. I still looked exhausted, with dark circles under my eyes, and I was still losing weight. At that point my mother realized that the problem was more serious than my simply being a little thin. She took me to another doctor, who was educated enough about eating disorders to diagnose my anorexia. When I saw the word anorexia on my chart for the first time, I freaked out. I was terrified that my disorder would be taken away from me. And, most of all, that they would make me gain weight! Although on one level I didn’t want to live with my eating disorder, on another level I was petrified of living without it. It was the only aspect of my life that I believed to be in my control, and there was no way I was willing to give that up.

If my guidance counselor asked what I’d eaten that day, I’d come up with a whole list I could rattle off so convincingly that I sometimes got angry with myself for eating things I actually hadn’t eaten.

I was put through a battery of tests that showed I had very low blood pressure, a very low heart rate, reduced kidney function and full-blown osteoporosis. You’d think hearing all that would have scared me into recovery, but no, it didn’t. Then the doctor asked when I’d had my last period, and I just cracked up. He asked me why I was laughing, and I responded, “Oh, N/A!” “N/A? What does that mean?” “It means ‘not applicable.’ I’ve never gotten a period.” “And you’re seventeen and a half?” “Yes, but it’s okay. I’m a ballet dancer. We don’t get those.” “But you’ve never gotten your period? That’s not good. That’s contributing to your bone loss and a lot of other things, too.” My body was being starved, and we all need to eat. We need fuel, and my body was getting that fuel wherever it could—internally, from my bones, from my body fat and from my muscles.

The doctor looked at my mother and said, “Just give her some of your good French cooking.”

The doctor then told me that I’d probably have fertility issues in the future, and my response to that was “Good. I don’t want to get fat, anyway.” Sad as that may sound, I simply had no sense of the danger to my health. I couldn’t see past the present moment. In that moment all I wanted to do was dance, and I knew that I needed to be thin to dance. Honestly, it was the only reason I was living at that time.

On one level I didn’t want to live with my eating disorder; on another level I was petrified of living without it.

Even though the doctor knew enough to diagnose me, he still didn’t know how to treat me. His approach was to give me hormones and steroids to bring on my period and stimulate my appetite. Basically, he was going to fix me with medication. I was still restricting my food intake, but because of all the medications I was taking, I gained weight. In a matter of three months I doubled my body weight! Please note, I’m purposely not giving you numbers here, because I would never want my number to become a goal weight for anyone else. If you’re struggling with an eating disorder, I can guess that you focus on numbers—the number of calories, fat, carbohydrates and proteins in foods you eat; the number you see on the scale; and the number you believe would be perfect. I also need to say right now—because I know that if you’re reading this, you’re probably thinking, That’s it, no treatment for me! No one is going to make me gain that much weight!—that it is extremely unlikely something like that would happen today.

The diet gave me back my sense of control. My anorexia and the exercise bulimia came back with a vengeance.

For me, however, the doctor was giving me all those medications at a time when I felt completely helpless. Up to that point I had always felt as if I were in control, but now, no matter what I did, the drugs were causing me to gain weight. I was incredibly anxious and depressed, and I felt as if everything I’d worked so hard to attain, including my ability to dance, was slipping through my fingers like grains of sand. I was starving, and I figured that since I couldn’t control my weight anyway, I might as well just eat and use the food to numb all those negative feelings. That was when the bulimia started. I never used self-induced vomiting, but I would binge and then purge with laxatives and compulsively overexercise.

At that point, I was about to graduate high school, and this was the time when I should have been auditioning to join a ballet company, but by that point I was too big to be a ballet dancer. Instead, I determined to use the next year to get myself back in shape and back on track. I stayed home and continued to dance at the academy where I’d been studying. By then I was in the most advanced group, so my classmates and I were often invited to take company class and sometimes also given roles in their productions.

Now I didn’t know who I was. My only remaining sense of identity came from my eating disorder. I had, in essence, become my eating disorder.

At the same time, without telling my primary care physician, I also went to see a doctor who was a metabolic specialist and who already knew my history. I remember her asking me what I wanted more than anything in life. I said it was to dance, and she told me that she’d help me make my dream come true. Her way of doing that was to put me on a totally insane plan that involved my taking about thirty supplements a day (to date I still don’t know what was in them) and going on a refined Atkins-type diet. Although I knew it wasn’t healthy and was the last thing that I should have been doing, it gave me back my sense of control, and, in fact, I did start to lose weight.

As I began to regain a (misguided) sense of confidence, I auditioned and was offered an apprenticeship with a ballet company in Orlando. By then I’d achieved what the metabolic doctor considered to be my goal weight, so she took me off most of the supplements I’d been taking. I was supposed to be maintaining my weight, but once I was on my own again, I began to restrict even the meal plan she’d given me and I stopped taking the medications that had been prescribed by my primary care physician. My anorexia and the exercise bulimia, which had never really gone away, came back with a vengeance, and I fell back into my disordered eating really hard and really quickly. About six weeks later my mother came up to Orlando to see me perform, and, of course, she noticed how much weight I had lost.

If I were given a second chance in this journey called life, I would help others battle eating disorders so they wouldn’t travel down the same path I did.

By then I was nineteen years old and really, as the saying goes, sick and tired of being sick and tired. Both my parents and my doctors had speculated that if they took ballet out of the equation, my eating disorder might just go away, and I actually thought so, too. After all, I really believed that the whole thing had started because I wanted to lose weight in order to be a more beautiful dancer. And I even remembered that when I was in high school, I’d look at the kids who were music students and think, Wow, if I were a musician instead of a dancer, I could eat anything I want. I don’t believe it anymore, but at the time the idea that my dancing had caused my eating disorder seemed pretty logical to me.

I resigned from the company and thought that my eating disorder would go away immediately. Boy, was I wrong. In truth, dancing was the only thing that had been keeping me alive. Aside from my eating disorder, it felt like my only identity. Now I didn’t know who I was. My only remaining sense of identity came from my eating disorder. I had, in essence, become my eating disorder.

I was alone in Orlando with nothing to do, and I was floundering. I’d never intended to go to college, and I’d never considered what I might do with my life if I wasn’t dancing. I started to binge more and more, because I thought that was the only way I had to relieve the pain I felt. If you’ve binged yourself, you know that it has nothing to do with enjoying the taste of the food you’re eating. Actually, in the moment, you don’t taste anything at all. It’s all about stuffing down (or numbing) and running away from any kind of feeling or sensation. After I binged, I felt awful and guilty about what I had just done. When I was restricting, I felt good about myself because I felt that I was in control. When I binged, I felt an enormous loss of control.

I called my parents and, for the first time, admitted to them that I really needed and wanted help.

I remember waking up at two o’clock one morning and realizing that I had no sense of who or what I was. My parents had been urging me to go back to school, and I decided to enroll in a psychology course at the local community college, thinking that I might gain some insight into what was going on in my own mind. It was while I was taking that course that I made another decision: if I were given a second chance in this journey called life, I would help others battle eating disorders so they wouldn’t travel down the same path I did. Since all I knew besides ballet was my eating disorder, I determined that I would become a therapist specializing in eating disorders. After sticking my toe into academic waters, I went back to college full-time, entering the University of Central Florida in January 1998 and, in true perfectionist style, starting to follow an absolutely ridiculous, stressful schedule. (I actually graduated college in two and a half years…which is definitely not a healthy thing to do.)

I really had nothing in my life to focus on except school, and being focused on school became another way to numb my feelings. So that was where I transferred my obsession, taking more than the required number of classes. Given that I was in a cycle of restricting during the day and then, when classes were over, going back to my apartment and bingeing, my career choice was at the time somewhat ironic and, in retrospect, unrealistic. By that point I was wearing plus-size clothing, and to say that I was not a healthy girl (mind, body and spirit) would be the understatement of the century. But I knew that if and when I got better, this was what I wanted to do with my life.

In pursuit of my newfound career objective, I called a few local practitioners who specialized in eating disorders and asked whether I could become an intern or shadow them in their practice. They all told me that because of confidentiality issues, they couldn’t allow me to do that, but one of them also told me about the International Association of Eating Disorders Professionals (IAEDP), an eating disorders organization that had just relocated to Orlando and was looking for volunteers. I called the executive director, Dr. Marie Shafe, who asked me to come in for an interview. She turned out to be one of the most amazing and inspiring people I’ve ever met in my life, and she urged me to volunteer. Before long, I progressed from volunteering to a paid position. I started to help out in the office, working on the newsletter and working alongside the director as her assistant. By that time it was the year 2000. I was in college, applying to graduate schools and working when I realized I was actually falling apart at the seams. I was realistic enough to know, after taking so many psychology courses, that I couldn’t go to graduate school and learn to help other people until I’d helped myself. I called my parents, told them that I was putting graduate school on hold and, for the first time, admitted to them that I really needed and wanted help. I’d also confided in Dr. Shafe, and she helped me get into an outpatient treatment program.

Over the years I’d been to see many different therapists on several occasions, but until then I’d always told the therapist exactly what I knew he or she wanted to hear, and that was it. I simply wasn’t ready to hear what the therapist had to say to me. I wasn’t ready and willing to see a life without my eating disorder. I’d go to a nutritionist, take the meal plan I was given and throw it in the nearest trash can before I even got home. In other words, I manipulated everyone and sabotaged myself in order to maintain my eating disorder, which felt safe to me. The thought of giving up the eating disorder and going into an unknown place was much more frightening than maintaining the familiar, miserable as it was, and suffering the consequences.

I was still thinking in black-and-white, all or nothing. I was going to do recovery the same way I’d approached anorexia, wholly and completely. I slipped, as we all do, and boy, did I ever beat myself up.

But this was different. Now I had a nutritionist, a therapist and an entire treatment team, and I was truly ready to take back my life and get better. For the first time in my life I began to understand the feelings that underlay my eating disorder: why I hated myself so much, why I felt so undeserving, why I felt that everything had to be perfect. At first it was very scary to feel again after avoiding those feelings for so long. I didn’t like it one bit, but once I began to understand that I didn’t need to be perfect, that recovery wasn’t going to be perfect, I started to breathe again. It wasn’t easy, and I could not have done it if I hadn’t already come to the realization that I wanted to get better and was ready to do whatever was necessary for me to get healthy. Up to that point, I honestly hadn’t been willing; I just didn’t want to. No one—including me—could love me enough for me to be encouraged to get better. I’d devoted ten years of my life to my eating disorder, and now, for the first time, I wanted to live, laugh and feel good about myself again. I even wanted to go on a date. At the time, I hated my body so much that I was literally avoiding any kind of contact at all with the opposite sex. Instead of checking out the guys, I spent my time sizing up other women and comparing them to myself—and, not surprising, I was always the one who came up short. I felt as if someone had taken away my soul, and now I wanted it back.

Never once in my entire life had I awakened in the morning, looked out the window in sunny West Palm Beach and said, “Today I’m going to become an anorexic.”

I started to get better, but things didn’t immediately become all better. In fact, my recovery process was far from easy, predictable or perfect. That was yet another hugely important realization for me. Initially, I was still thinking in black-and-white, all or nothing. I was going to do recovery the same way I’d approached anorexia, wholly and completely. I’d decided to get better and, therefore, I would be completely better immediately. I would be the Queen of Recovery—at least that was what I thought. Of course, it didn’t happen that way; it simply isn’t possible. I slipped, as we all do, and binged—and boy, did I ever beat myself up afterward. As was typical for me, I used my slipup as an excuse to keep telling myself that obviously I wasn’t good enough to do even recovery correctly.

Slowly, however, my journey to recovery was progressing and I was gradually getting healthier, which meant that I was also seeing things more clearly—at least some of the time. Part of that clarity involved coming to the realization that I wasn’t going to be able to counsel people with eating disorders in a one-on-one therapeutic environment while I was still recovering myself. That relationship would simply be too intense and triggering for me, and I didn’t think I’d be able to maintain the proper therapeutic distance. In my heart, I knew I wanted to speak publicly about eating disorders because, as I was struggling with my own recovery, I really didn’t have anywhere or anyone to go to for support. It was completely up to me to hold myself accountable and go to my treatment sessions. I had a wonderful family and wonderful friends, but none of them really knew how to provide the support I so desperately needed. How could they have known? I was living by myself in Orlando, I didn’t confide in them, and therefore they had no idea what I was really going through.

There were several times when I could have easily lost my battle with my eating disorder, but I hadn’t.

I didn’t want anyone else to have to walk that path alone. I didn’t want them to think that they couldn’t get better. I wanted to walk beside them when they were going through the same thing I had so that they would know they were not alone. During the entire time I was in treatment, I had never known a single person who got better. I was white-knuckling it the entire way, and I wanted to make it different for others. I loved the work I was doing at IAEDP, but I wanted to get out there and bring education and awareness to boys and girls who were the “me” I’d been in seventh grade. I wanted to tell them that I knew what they were thinking—that they thought they were in control, that they could just lose some weight and then stop. I’d walked through that door, so I knew that once it slammed shut behind them, they’d have no way to get out. Never once in my entire life had I awakened in the morning, looked out the window in sunny West Palm Beach and said, “Today I’m going to become an anorexic.” I wanted them to know that, and I wanted them to understand that if they walked through the same door I had, it might be the same for them.