По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

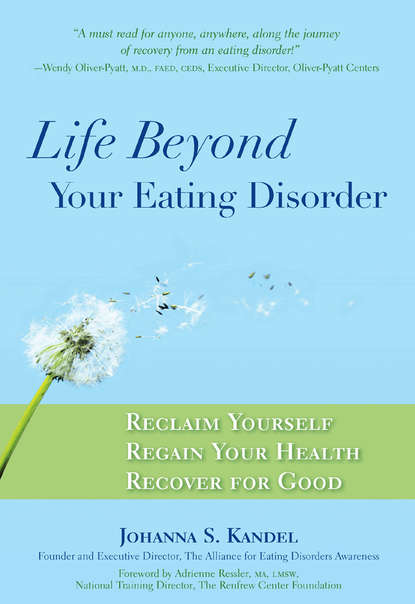

Life Beyond Your Eating Disorder

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Bridezilla or Brideorexia? (#litres_trial_promo)

Stay Focused and Just Say No (#litres_trial_promo)

Whatever the Occasion, Keep Your Eye on the Prize (#litres_trial_promo)

Afterword: re(Define) (Real)ity

I Define What’s Real (#litres_trial_promo)

Recovery Means Steering Your Own Course (#litres_trial_promo)

Me 101 (#litres_trial_promo)

Accept the Gift That Is Offered (#litres_trial_promo)

What I Wish for You (#litres_trial_promo)

Getting Help

Acknowledgments

About the Alliance for Eating Disorders Awareness

About the Author

Foreword

JOHANNA KANDEL BEGINS THE PREFACE of this wonderful book with a disclaimer, saying what she is not—not a psychiatrist, therapist, nutritionist or doctor of any kind. She does say that she is a recovered individual who knows the physical and emotional journey of those who struggle with an eating disorder. But, oh, Johanna is so much more than that, as those of you reading this will certainly realize by the last chapter. She is a visionary, an activist, a healer, a teacher, an organizer, a warrior, a negotiator, a mediator, an author and an optimist. She is an inspiration to all whose lives she has touched, but never has she wanted to be a role model to be admired, copied or looked up to. This book provides many tales of recovery to help readers understand that there are many paths to healing, each as unique as the traveler herself. The message reinforced here is that there is no room for competition or perfection in recovery—no glory in being the fastest, the best, the thinnest or the most popular. Recovery is a process and the right process is the one that works best for you.

I have been involved in the field of eating disorders for almost thirty years, specifically in the area of body-image treatment and training. I met Johanna when she was nineteen years old and a volunteer working at the International Association of Eating Disorders Professionals (IAEDP) Conference. Just as Johanna has changed and grown since that time, so has the field of eating disorders itself. We now know more than we ever did before about the complexity of eating disorders: their connection to other psychiatric disorders, the gender-biased risk factors, the role of the brain, genetics and one’s temperament as variables, the connection between body shame and the culture, and the importance and effectiveness of complementary treatment modalities such as art therapy, dance/movement therapy, spirituality and yoga. Research has given us more information and more tools. We need to always keep the belief alive that recovery is possible, that no recovery is “perfect” and no one should ever give up. It may be useful to know that the word recover comes from the Latin and means “to bring back to normal position or condition.” Therefore, the person we discover during recovery is not someone new, but someone we have once been, a person whole and integrated. Recovery needs to be viewed as a continuous process that allows for the development of a greater sense of oneself, not a definite end of symptoms.

Years ago I came across the following passage in the book On Death and Dying by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross. I share it here because I associate it so closely with the struggle involved in freeing oneself from the grasp of the eating disorder:

It is not the end of the physical body that should worry us. Rather, our concern must be to live while we’re alive—to release our inner selves from the spiritual death that comes with living behind a façade designed to conform to external definitions of who and what we are.

Like a vampire who takes the very lifeblood from the innocents who fall under his spell, so, too, the eating disorder takes the very life spirit of those who relentlessly pursue the seductive belief that their true selves do not measure up to societal expectations and substitute a “perfect” self in order to be acceptable. Recovery involves a reclaiming of one’s true self, giving up the eating disorder identity, making peace with one’s body, shifting away from negative self-talk, relinquishing a victim mentality and staying optimistic despite setbacks and difficult times. As Dan Millman, author of Way of the Peaceful Warrior, said, “You don’t have to control your thoughts; you just have to stop letting them control you.”

Life Beyond Your Eating Disorder is a true recovery guide for individuals at any stage of eating disorder treatment or recovery. It is also excellent for families and friends to better understand how to provide support while maintaining their own lives. The book provides a candid, comprehensive look at the ups and downs of recovery and offers tips, resources, hands-on tools and strategies for breaking free from the distortions and beliefs that make up the world of the eating-disordered individual. The book is exceptional, as is its author.

Adrienne Ressler, MA, LMSW

National Training Director for the Renfrew Center Foundation

President, International Association of Eating Disorders Professionals (IAEDP)

Preface

MY MISSION

I learned this, at least, by my experiment; that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours.

—WALDEN, HENRY DAVID THOREAU

I’M NOT A PSYCHIATRIST; I’m not a psychologist or a therapist or a nutritionist or a doctor of any kind. But I have been an anorexic, an exercise bulimic and a binge eater, and if either you or someone you love is struggling with an eating disorder, I can honestly say that I know what you’re going through—maybe not the day-to-day details, but certainly the physical and emotional landscape of your struggle.

Perhaps one of the most important and startling things I learned both during my ten-year battle with an eating disorder and during my recovery is just how much ignorance, misinformation, fear and stigma are still attached to eating disorders even in the midst of the so-called information age. The entire time I was struggling and during my recovery process, I never knew anyone who had successfully recovered from an eating disorder. Truthfully, I didn’t know if recovery was even possible. All I knew was that I was sick and tired of being sick and tired, so I decided to seek help.

As I began my own journey to recovery, I vowed to myself that if I were given a second chance at life, I would do everything in my power to dispel some of that darkness and bring eating disorders awareness and information into the light. I strongly believe that no one should have to struggle with or recover from an eating disorder alone.

No one should have to struggle with or recover from an eating disorder alone.

Eighteen years ago, when I first began to develop my eating disorder, I had no idea how many people had the same terrible disease. I honestly believed I was one of the very few. But here are the facts: according to the Eating Disorders Coalition, today, in the United States alone, approximately 10 million women and 1 million men are struggling with anorexia or bulimia, and 25 million people are battling binge eating disorder. Eating disorders do not discriminate; they affect men and women, young and old, and people of all economic levels. You need to know that anorexia nervosa has the highest mortality rate—estimated to be up to 20 percent—of any psychiatric illness. And only one in ten people with an eating disorder receives any kind of treatment. Those figures make me sad and are, quite simply, unacceptable.

As I began to recover and find my strength, I kept the promise I had made to myself all those years ago, and in late 2000 I founded the Alliance for Eating Disorders Awareness in my hometown of West Palm Beach, Florida. The Alliance is a nonprofit organization whose mission is to prevent eating disorders and promote positive body image by advancing education and increasing awareness. To this end we do community outreach through talks at schools, we provide educational programs about eating disorders to therapists and other health-care professionals, we lead support groups for people in recovery and we do whatever we can to convince government officials that eating disorders ought to be a health-care priority. For specific information about the Alliance, see page 215. I believe we are fulfilling that mission with each person we are able to reach and inform that he or she is not alone and that recovery is possible.

I know how difficult the recovery process can be, but I want you to know that it is possible to get better—and it’s definitely worth it! We all trip and fall along the way. But recovery is not about the trips and falls; it is about what happens after you pick yourself up. It’s about getting back on your feet, dusting yourself off and moving forward, because that is how we learn. Realistically, neither life nor recovery is ever going to be a fairy tale, but we do have the power to create our own version of a real happily-ever-after.

It is possible to get better—and it’s definitely worth it!

Give yourself permission to imagine your life beyond your eating disorder. You will get to be present in every moment; you will get to feel; you will get to laugh. You deserve the freedom to live every aspect of your life.

Eating disorders can be very strong—mine spent years telling me all the things I couldn’t, shouldn’t or wasn’t good enough to do. That negative voice isn’t going to go away overnight, but there are many tools available to you as you recover to make that voice smaller and softer, and you need to gather and use every one you possibly can. This book is one of the tools you can use to free yourself from your eating disorder once and for all. As you read it, I hope the voice you hear in your head will be healthy, supportive and powerful enough to drown out whatever doubts you may still have about your ability to recover. I’ve gathered the tools that I offer here through many years of working with eating disorder practitioners, in support groups, walking next to people on their journeys to recovery and by becoming aware of what has helped others. And I hope that these tools will be as useful to you as they have been to me and to so many others. I’m sure some tools will be more useful to you than others, and that’s okay. I wouldn’t expect it to be any other way. The idea is simply to be willing to try, and if one thing doesn’t work, try something else. Just don’t stop trying.

We have the power to create our own version of happily-ever-after.

As you read on, you will come upon the stories of many different people from many different walks of life who have recovered from eating disorders, and you will come to see that they have followed many different paths. And just as there is no right or wrong way to recover, there is no right or wrong way to use this book. You might read it from cover to cover, or you might choose to read a few chapters and ponder them for a while. You might even decide not to begin at the beginning but to pick a chapter that looks interesting and read that first. Whatever works for you is the right way.

Lao Tzu, the sixth-century BC Chinese philosopher and father of Taoism, said, “A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.” Taking that first step toward recovery is really hard, and I admire you so much for taking this first step. You have come so far just by picking up this book. I know that together we can keep moving forward so that you, too, are able to create a new reality for yourself.

Chapter One

FOOD FIGHT

Dedicate yourself to the good you deserve and desire for yourself. Give yourself peace of mind. You deserve to be happy. You deserve delight.

—MARK VICTOR HANSEN, AUTHOR OF CHICKEN SOUP FOR THE SOUL

MY STORY HAS BEEN TOLD MANY TIMES. The specifics of my particular journey may be different from yours or someone else’s, but the basic story line remains the same. Since you’ve so graciously allowed me to walk beside you on your journey to recovery from your eating disorder, I think it only fair that I tell you something about my own experiences along that path. I don’t expect that your experiences will be exactly the same as mine, but I’m sure that at least some of what I describe will be familiar to you. And, really, the point is that whether or not you follow precisely in my footsteps, you, too, can and will arrive at a place where your eating disorder is no longer the first thing you think about the moment you wake up in the morning, the last thing you think about before you go to sleep and what you think about almost every moment in between. My hope is that this book will help to make your journey a bit easier as you travel your own path.

Let’s begin at the beginning. I was born and raised in West Palm Beach, Florida, but both my parents were raised in France. My father was a Holocaust survivor. When he was just four years old, his father was sent to Auschwitz. My father and his mother, my grandmother, were then separated from one another and went into hiding with different families in different places. Separated from both his parents for five years, my father missed out on much of the nurturing and early education he would otherwise have had during this critical time in his development. His father died in the concentration camp, but he and his mother were reunited after the war. Once he had completed his schooling, my father came to the United States to start a new life, returning to France once a year to visit his mother. It was on one of those visits that he met my mother, who had been born in Algeria and moved to France when she was eight years old. She was one of seven children in a family of a very poor and humble background; on many nights my maternal grandmother went to bed wondering whether she would be able to feed her children the next day.

You will arrive at a place where your eating disorder is no longer the thing you think about the moment you wake up in the morning, before you go to sleep and every moment in between.

As a result of their own upbringings, both my parents were intent on giving me every opportunity to soar in every aspect of my life, but they also had very high expectations of me. While my mother was the nurturer, very affectionate and simply wanting me to excel at whatever I did, my dad was very much the perfectionist. He expected me to become a doctor, at the very least, or perhaps even a nuclear physicist. Because I was an only child, all their hopes, dreams and expectations were invested in me. Today I understand that if they pushed me, it was because of the potential they saw in me, but at the time their expectations translated in my mind to a belief that I just wasn’t good enough to live up to the standards they—and my dad in particular—had set for me. But I tried. I always did as I was told, never gave them a hard time and put a lot of pressure on myself to do whatever I could to make them proud.

As a little girl I was extremely pigeon-toed, so my parents thought it would be a great idea to enroll me in ballet class to improve my grace and posture and help straighten out my feet. Much to their dismay, from the moment I got into that class, all I wanted was to become a ballerina. My mother continued to be supportive, but my father told me only recently that he had never expected me to become a dancer and had, in fact, been somewhat horrified by my announcement. Nevertheless, I started to dance at a local ballet academy and my training became very intense very quickly. By the time I was seven, I was already on a professional track. My parents had also enrolled me in various other classes, including gymnastics and piano, but my one true love remained ballet, and by the age of ten I was dancing four to five nights a week.

The summer before seventh grade, when I was twelve, I attended ballet camp in Chautauqua, New York, where I studied under a very well-known ballerina. I remember her saying that as dancers we needed to be “light as a feather” and the most beautiful ballerinas we could possibly be. Although she was undoubtedly talking about technique as much as weight, I immediately internalized the message that if I wanted to achieve my dream, I would have to be thin. If my dad had high expectations of me, mine for myself were even higher. Having internalized his message, it was no longer his voice but mine inside my head telling me that if I was going to do something—whatever it was—I needed to do it perfectly.