По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

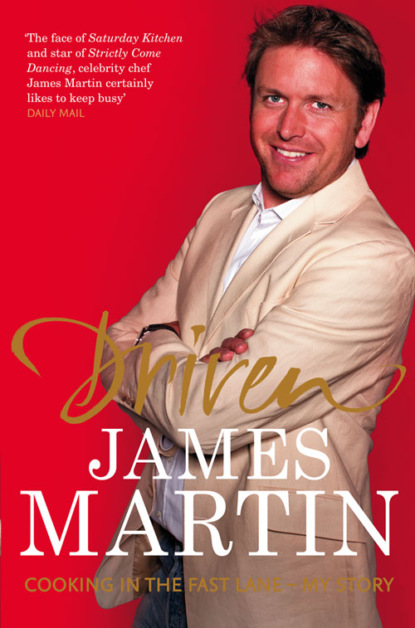

Driven

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

When it comes to education, I’d say some of the most important things I learnt came from going on trips to France with Dad in his HGV. My dad has spent his life being a jack of all trades, and he’s actually been very good at some of them. He was not only a renowned sommelier and judge on the Jurade de Saint Emilion, he was also one of the two main UK importers of wine from the Bordeaux region. Always keen to save a couple of quid, he didn’t just import the wine, he got his HGV licence, hired a lorry and went to collect it himself. And I used to go with him.

I was never good at school. I even failed cookery. I was always just too thick to be academic. My sister was the one with the brains and I was more practical. If it involved anything written I wouldn’t be able to do it, which was one of the reasons I failed cookery, or ‘home economy’ as it was called then. I say one of the reasons; I’m convinced the other was that the home economy teacher hated me because I could cook better than she could. I think everyone just assumed I wasn’t putting any effort into my written work, but that wasn’t true. I’d sit there for hours, night after night, trying to write up how to cook an angel cake, or put into words the concept for a new design of kitchen cupboard, and I’d always get a D for it.

Actually, look at my school books, and the diagrams and illustrations that went with the writing were always incredibly detailed and painstaking, which should have given someone a clue that I was putting more than a D’s worth of effort in. In truth, those drawings took half the time it took me to do the writing yet would easily get me an A. If not the quality of those drawings, then the effort I put into practical work was surely enough to make anyone who was half awake realise that I had a genuine passion for the subject which my writing wasn’t reflecting, and that maybe there was something more fundamental wrong. But my teacher was too busy filling my exercise books with must-try-harders to notice that it was only the words that were the problem.

As for English, I didn’t even try to concentrate on it. What was the point? Shakespeare, Dickens – what good were they to me? My brain just switched off to anything printed that wasn’t in a car magazine. Put me in art or cookery, doing something creative or practical, and I came alive; get me to read out loud, and I was like the slow kid in the class. It wasn’t until much later, when I first had to read an autocue for Saturday Kitchen, that someone worked out I wasn’t the thick kid after all, I was in fact dyslexic.

I was 13 when we first went over to the South of France together to collect the wine. It was a week-long round trip: two days there, two days back, and the rest of the time he’d leave me in a French chateau to learn what French food was really all about. Through Castle Howard and his connections with Saint Emilion he knew the families who ran these great old chateaux and they were more than happy to have a young wide-eyed wannabe chef stay for a few days. Every visit was to somewhere different, but every time it was just as incredible and eye-opening. You couldn’t imagine a greater culture shock if you tried. I was growing up in England at a time when a Berni Inn was considered an exotic place to eat. If it didn’t come with chips and an all-you-can-eat salad bar it was completely alien. All of a sudden I was being dropped off at these big family houses where some of the greatest chefs in the world had trained and I was being looked after by the lady of the house who had in her head the entire history of French cooking.

These were some of the best chateaux in France – Figeac, Pressac, Cheval Blanc – so I was meeting real experts, the people who actually trained the chefs. It wasn’t restaurant food, it was authentic rustic French cooking, the foundations and building blocks of every great French restaurant. It was proper French food, at its very best, and I was in there, taking it all in, while my dad was off in Saint Emilion sorting out his HGV-load of wine.

This was my first experience of good wine and food (there was no such thing as shit wine or food out there). And it was my first experience of proper French food: foie gras, truffles and pigeon – not just pigeon breasts, but pigeon, with the head still on. It was also my first real experience of markets. At home, if you had to go food shopping it was off down to Sainsbury’s. Here, the cook would take me to the local market, point at a quacking duck in a cage and say, ‘Canard.’ And I’d be going, ‘Yeah, yeah, duck.’ The next thing, the duck would have had its neck wrung and it’d be lying in her shopping basket. They didn’t do that at Sainsbury’s. We’d pluck it, dress it, keep the head on, and while the duck was in the oven the cook would pan-fry the liver and spread it on a piece of toast for me. And there was no ‘I don’t fancy it’. You were eating it, and that was that. Put it this way: it made for a very sharp culinary learning curve.

I learned so much so quickly in those kitchens, but if there’s one thing I learned quicker than anything else it was that the secrets to great cooking are fantastic ingredients and passion. For the French, cooking is all about going to the market, spending time looking around, picking out the freshest meats and vegetables, something which as a young boy from England I just wasn’t used to. In these villages they didn’t have a local supermarket, they had stalls in a square with absolutely everything you could ever want on them. It was amazingly exciting – the colours, the smells, the noise of the animals. It was an eye-opener, but a great one.

I went back year after year, at first with my dad on the wine runs in the HGV, then when I was at catering college on six-week blocks of work experience. I was cooking in two-star Michelin kitchens in my teens, and my head spun with it all. It was all light years ahead of anything we learned in school (or even catering college), and being 15 and versed in the ways of true French culinary excellence didn’t always go down so well. In fact, one time it almost got me expelled.

One day our teacher informed us that the following week we could cook whatever we wanted. So a few days later all the girls – and there were 24 girls in my cookery class at school, and three boys, which was probably what attracted me to it in the first place – brought in the ingredients for Black Forest gateau, Swiss roll, nut cutlets and angel cakes with buttercream. I brought in what I needed to make chicken livers flambéed in brandy with a mange tout and rocket salad. Amazingly, the teacher was not impressed. I was in the corner, flambéing away, when she suddenly shouted out, ‘James! What do you think you’re doing?’ I said, ‘Er, flambéed chicken livers with a mange tout and rocket salad.’ But instead of getting marks for initiative, technique, presentation and taste, she just pointed out that I was flambéing with brandy and pupils weren’t allowed to bring alcohol to school. Ah yes, that.

The benefits of my French work experience placements may have been totally lost on that occasion, but when it really mattered they were spotted immediately. My first week at catering college, when I was 16, was a defining moment in my life. I wasn’t starting further education with ambitions to be a star pupil. I’d been at Scarborough Technical College for a couple of days when the head lecturer, a guy called Ken Allanson, who’s still a great friend of mine, came to give the new intake of students the once-over. Ken taught the third years, who were like the SAS of the catering college. At the start of the first year there were 120 numpties, most of whom thought a bit of cooking would be an easy option. By year two that number was nearly halved to those who were quite serious about it, but by year three all that were left were the dozen or so hardcore students who desperately wanted to do it as a career. Those are the students Ken taught, so when he came into the room everyone was shitting themselves.

We were all there, immaculate in our starched-to-buggery jackets which were as stiff as boards (so stiff you couldn’t move your arms in them), with our overstarched tea towels that wouldn’t soak up anything, all dressed to impressed, and Ken, who had been walking around watching us during the lesson, came up, put his arm round me and said, ‘You’re not a bad cook, are you?’

I was 16. No one had ever before had a good word to say about me in a classroom. I was absolutely bricking it.

‘No, chef,’ I said.

He nodded, smiled and added, ‘I’ll have to keep my eye on you.’

And that was it, probably the defining moment of my life and career. That one compliment made me suddenly believe I might actually be able to do this, not in an arrogant way but in an I-can-make-something-of-myself-after-all kind of a way. I knew from that moment on that it was worth getting my head down. True to his word, Ken kept his eye on me throughout college, always steered me in the right direction, and saw me being offered jobs by practically every one of the top chefs who came to judge my year’s final exam.

I pretty much owe my entire career to Ken Allanson. He managed to keep me humble and hungry enough to learn while building my confidence and self-belief. But most of all I owe him for spotting the excitement and passion those French wine trips had instilled in me, and for undoing all the damage my uncharitable and unforgiving former cookery teacher had done over the years. In the time it took Ken to come over and say those few kind words, the inside of my head completely changed. I went from bottom of the class to number one; from the one who’d never get anywhere to the one to watch. I’d known since the age of seven that I wanted to be a chef, but if I had to narrow it down and pick a moment when I knew for sure it was what I was going to do with my life, well, that was the one.

10 ‘EXTRA-CURRICULAR’: THE WHITE VAUXHALL NOVA (#ulink_c2a89e47-36c0-57cc-85a0-5769d492d4bd)

The first car I had was a white Vauxhall Nova, 950cc, the one with the boot on the back that no one wanted. My dad paid £250 for it. It was a cut’n’shunt job: not two, but three smashed-up cars welded together. Although I’m not sure why they bothered, or why, if they were going to all that trouble, they didn’t pick the more attractive hatchback option for the back end. Or, for that matter, why they didn’t pick a better interior: it had the same horrible brown chocolate-crumb-magnet cloth as my dad’s old Ford Capri Laser 1.6. Still, while it was definitely a complete crock of shit, and probably bloody dangerous, aside from a couple of weeks during which it was in for repairs, it was a loyal and reliable thing. It got me through catering college. I had it all the time I was working in London, too, which was nearly two years. It even survived a car park crash on my first day at Chewton Glen, one of the most prestigious hotels in the UK. Of all the cars I’ve owned, I had that white Nova the longest. It saw me go from young, enthusiastic and unqualified practically all the way through to becoming a head chef. And that’s a lot of action. Though not the most glamorous or exciting of cars, it was an important one.

For the first month after passing my test I drove the Nova the 40 miles from home to college every day. Eventually my mum said that I really needed to get digs because travelling backwards and forwards was ridiculous, so I found a place with my old school mate David Coates, who was also at Scarborough doing catering, and another bloke called Malcolm. The flat was above, of all places, Henry Marshall’s amusement arcade on Scarborough seafront, the same Henry Marshall’s where I’d seen my first Aston Martin V8 Vantage nine years earlier. But I would still drive back home in the Nova every weekend to work in the kitchens at Castle Howard or to cater for functions for my dad’s friends.

I was bombing it back from college one Friday night, about midnight, when I almost ran into our local bobby. It was dark, I was driving too fast, and I came tearing round this corner and he was just sat there in his car, glaring headlights, eyes out on stalks, looking like he had myxomatosis, with a sandwich in his gob. I came round this corner sideways, just missed him, straightened up and drove as fast as I could up through the village. I knew he’d know exactly who it was – it was a very small village – but being 17 and not thinking straight I drove home, straight through the gates of the farm, turned the lights off and then drove about a mile and a half up this track, thinking that he’d never follow me up there. I then ran back to the farm and hid in the pig sheds.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: