По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

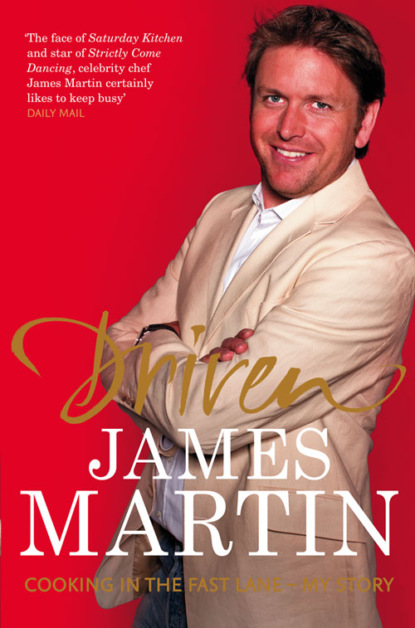

Driven

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I could do allsorts on my Aero-Pro Burner, especially once I’d tricked it. I put pegs on the front and back, like extended wheel nuts that you’d stand on to do tricks; I used them to do front bunny-hops and rear bunny-hops. I could also do front and rear bunny-hops on the pedals – much harder than on the pegs. I used to do the thing where you’d drive along, hit the front brakes so the rear end would go up, and you’d flick it round and on to something like a bench; if you had enough momentum you could bring the front up as well so the whole bike was on the bench; then you could do some bunny-hops on the pedals and jump back off again. I could even do the move where you applied the front brake, kicked the back end round and literally stepped over the frame as it swung round you. That was pretty cool. I could do loads of other things too – pick it up off the floor just by standing on the pedal, wheelies, all the usual stuff – but those were my coolest moves. I used to change the hand grips, which were a bit of a bugger to do because you had to use a scalpel to get the old ones off (and with my track record for blade injuries that was asking for trouble), then to get the new ones on you had to slide them on with Fairy Liquid, and then you had to wait for them to dry and set otherwise they’d forever be twisting round. I used to change the forks and the handlebars as well, anything to make the bike cooler and better for stunts.

I was obsessed with that bike; it completely changed my world. Before that I’d had a Raleigh Boxer, which was like a baby BMX. Mine was yellow, so it was sort of cool, but my neighbours had a Chopper and a Grifter, and next to those it was a case of little man/big man syndrome (‘How big is yours?’). My piddly little Boxer was, well, little. I couldn’t actually ride Grifters because they were too big for me. I couldn’t reach the floor. But I borrowed my neighbour’s Chopper once and that was really cool – or it was until I came off, and because my legs weren’t long enough to touch the ground properly I ripped my bollocks on the gear stick. That really bloody hurt.

Once I had the Aero-Pro Burner, though, it was a different story. I was the man, I was unstoppable. When I got that bike I suddenly got my freedom.

I rode absolutely everywhere on it. I used to bike the 5 miles to school every day, and that’s a lot of pedalling. Me and David Coates, who had an Xtra Burner which was all right but not as good as mine, used to ride out to this old campsite, next to the lake at Castle Howard. We’d do a circuit of the campsite and the guy who ran it always used to come out and shout and tell us off, but we didn’t care. We’d fly past and ignore him. One day he put a scaffolding bar across the top of the gate posts. We didn’t see it until it was too late. We were lucky it didn’t take our heads off. It was like some comedy sketch: one minute we were bombing along, standing on our pedals, the next we were swinging from a metal bar and our bikes were hurtling off into the distance without us. We could hardly breathe we were so winded. I’m not sure we went back there after that. But there were plenty of other places for two BMXers to get into trouble. Plenty.

The first time I got arrested I was on my Aero-Pro Burner. There was this disused farmhouse about 4 miles away from the back of our farm; no one had lived in it for ten years at least. One day David and I decided to ride over there. It was completely abandoned, like something out of Scooby Doo, so of course we climbed in through a window and found all this amazing stuff, like tankards, and playing cards with half-naked women on them. We thought, ‘Right, we’re having them,’ so we loaded them up and took them back to our den.

Our den was round the back of the farm. It was almost like a hayloft, with a rope ladder we used to get up to it. It looked really cool with all the loot from the old farmhouse in it. Then one day my dad found it. He realised what we’d done and he did what any reasonable protective father would do: he called the police. They came and took me away and put me in a cell. I was ten. There was no mention of David, it was just me, on my own, down the local nick. No one had been in this farm for a decade, it’s not like anyone was going to miss anything, but my dad wanted to teach me a lesson, and being an ex-copper he was mates with the local police, so they banged me up and left me in a cell for two hours. I got hauled in front of the superintendent and everything. Got a right ear bashing. It was almost as if my dad had orchestrated it all and told them exactly what to say. And it was all staged, but I was ten years old. I thought I was going down.

We never went back to the old farmhouse. Instead we found other ways to amuse ourselves, one of which involved a ramp and the local girls’ Brownie pack. I had this BMX ramp, a really, really good one, that I’d bought with my pocket money. It was 3 feet long with a strip of that non-slip black sandpaper type stuff up the centre for extra grip, and it had clips at the back so you could set it to different heights. We used to set it up in David’s back garden, or at the bottom of the hill on the farm. We’d both pedal furiously down the hill towards it, picking up a fair speed to the point where we couldn’t actually pedal as fast as we were going, we’d go flying off the end of this thing, and we’d go a pretty long way. Our other place to jump was outside the village hall. There wasn’t a hill to ride down, but there was a mound of grass by the car park which was perfect for giving the ramp extra height, so what you lost in run-up speed you made up for in launch angle.

Usually when we were trying to outjump each other we’d mark the distance with a stick. One of us would jump, the other would record the distance with the stick, then we’d swap. We could do that for hours. One day we were outside the village hall with our ramp when the local Brownies, who used to meet in the village hall, turned up. There they all were, gathering in the car park in their nasty brown dresses, yellow scarves and woggles, and there we were, jumping off our ramp and measuring the results with a stick. All of a sudden someone – and to be fair, I think it was one of the Brownies – came up with a great idea.

‘Why don’t we lie down, and you can jump us.’

Brilliant!

I reckoned I could jump 15 feet off this thing, which when you’re only 3 feet tall is a bloody long way, but I had no idea how many Brownies that would be, so we started off with two.

When the two Brownies were in place, we took as long a ride up as possible, pedalled furiously, went up the ramp and over. No problem. We put a third Brownie down, took a run up, pedalled furiously, got over, no problem. A fourth, a fifth and a sixth were added, and by the time we reached Brownie number 13 we were worn out from all the pedalling. We didn’t want to risk chopping a 14th Brownie in half so we put my sister’s big ted on the ground instead. We made it, just about, and then decided it was probably best to quit while we were ahead.

So that was it, the height of my BMXing achievements and my first real experience of women and some of their very strange ideas, all in one aerobatic stunt-riding go. Magic. What can I say? It was a small village in the middle of nowhere. We had to make our own entertainment.

7 BIKES AND TRIKES (#ulink_3413753a-8ba8-54a9-abd4-253c57b7029d)

The lime kiln at the far end of Lime Kiln Farm was this huge great mound, about 30 feet high, like a mini volcano, hollow inside with a big opening at the top. If you had a little motorbike (which I did), and you were a small kid (which I was) who had no fear (which I didn’t), it was perfect for riding your motorbike round the top of, daring yourself to get closer and closer to the edge, being careful not to get too close or you’d drop right into it, and it was a long way down. If I wasn’t jumping Brownies on my BMX or being thrown in a police cell for nicking playing cards with naked women on them, this is how I used to amuse myself.

I was about eleven when I got my first motorbike, a little Puch 50 twist-and-go scrambler. I went with my dad to Makro the discount supermarket one day when he was buying a load of drink for work, and this little bike was just waiting there. It was white with red and blue stripes and a sticker with PUCH written on it on the fuel tank. I gave it a proper look over. I sat on it and fiddled with all the bits and pieces. My dad was watching me, and after a while, once he’d got all the things he was there for, he just picked up a boxed one – it was only a little thing – and put it in his trolley. I asked him what he was doing, and he said, ‘You like it? You can have it. But you’ll pay for half of it.’ It was £150, and the maximum I’d earned that year was £40, so I had to come up with £75. Sure enough I worked to pay for it, pot washing like crazy, and the money went straight to my dad because he knew that if I got hold of the money he’d never see it. He wasn’t stupid.

I used to ride all over the fields on that thing. Either on my own or with my mate Philip Schofield. No, not that Philip Schofield. This Philip Schofield lived about 3 miles away and had an XT175, a massive bike for him and far too big for me, a big black thing with a black and white tank. Either I would cane it over to his and bomb around his fields, or he would come over to mine and we’d bomb around by the kiln. We had to stick to the fields though. I wasn’t allowed to ride out on the road on the Puch 50; for that I had my BMX. Even though we weren’t out on the roads, I always used to wear a crash helmet because I used to come off a lot, and of course the more confident you get, the more you come off, and I was always pretty confident on my little Puch 50. There wasn’t anywhere I wouldn’t go, and that included up the side of the kiln.

Because I was only small and the little Puch 50 was pretty light, if I had a good run at it I could usually get up the side of the kiln. But it was steep, and the inside was even steeper. You could drive up the outside, but you couldn’t then drive down into the hole and back up the other side to the top again because it was way too steep, practically a vertical drop when you looked down into it from the top. It was so steep that the inside would have made an almost perfect wall of death to ride round, if it hadn’t been for the big hole in the front, which was presumably where they used to put things into the kiln. Shame, that would have been amazing to ride round. It’s probably just as well though. The place was lethal enough as it was.

I took incredible care of my little Puch. I had it for about a year, and when I wasn’t testing my skills to the limit I was cleaning and polishing and taking good care of my pride and joy. Until one day it was nicked. I was gutted. It wasn’t insured or anything. My dad always said to me, ‘When you’re finished with it, lock it up and put it in the shed and then lock the shed to be on the safe side.’ And, like an idiot, I didn’t. One night I left it on the hard standing at the back of our house and it got stolen. I woke up in the morning and it was gone. I was heartbroken. I went in tears to my dad, who in typical style said, ‘You’ll learn, that’ll teach you.’ He didn’t say, ‘Don’t worry, I’ll get you another one,’ it was always, ‘You’ll learn.’ About three days later it turned up at the bottom of the village next to the telephone box. It had been completely stripped, all the leads had been pulled off it, and it had been set alight. It was just a burnt-out pile of bits, completely wrecked. I think the sight of that was worse than having it nicked in the first place. I loved that bike so much.

So that was that. My Puch 50 was no more. I was back to my BMX and working hard to save money to buy another motorbike.

Once I’d got a bit of cash together I went with my dad to the bike shop to look for a replacement. I was looking around at the Puch 50s, Yamahas and Hondas, and in the corner sat this shiny, brand spanking new Honda ATV70 three-wheeler. Now, these things really were lethal. No one knew that at the time, of course, but they ended up being replaced by quad bikes because they were so dangerous. It looked great in the shop and I said to my dad, ‘I like that.’ I only had about half the money though – my savings plus Christmas and birthday presents. I sat on it and thought it was really cool, but knowing that there was no way I could afford it I got off, had another look round and pointed out another small motorbike, nowhere near as nice as the trike but nowhere near as expensive either. I said to my dad, reluctantly, ‘I’ll have that one.’ My dad looked the little motorbike over, nodded and said, ‘Right, I’ll pay, you go and wait in the car.’ So I gave him my money and went and sat in the car.

Next thing I knew the door of the shop was opened and my dad was wheeling out the big Honda trike and pushing it into our horse box. I couldn’t believe it. I guess he must have liked it as much as I did.

We got home and filled it with fuel. My dad informed me that this was a serious bit of kit and that we were going to have to read the instructions. Then he was going to show me how to ride it. Like he knew how to ride it. I don’t think he’d ever seen one before, never mind driven one. But there he was, on the courtyard round the back of the house, looking it over like you do when you’re buying a new car, consulting the instructions and telling me that it had three gears, that’s the throttle, that’s the brake…

‘Right,’ he said when he’d finished his piece, ‘are you watching? I’m going to show you how to use it.’

He started it up with the pull cord (like the one you get on a lawn mower), sat on it, revved it up and put it into first gear. Only he still had the throttle on, and as soon as he released the clutch that was it, it reared up and fell straight back on top of him. He’s lying on his back in the middle of the courtyard pinned to the ground by this trike and I’m pissing myself laughing. And there ended my very first trike lesson. Still, there was an important lesson there for me, which inevitably I didn’t learn.

Blatting it up the side of the old lime kiln was easy enough on my little Puch 50, but on the Honda ATV70 it was a different story altogether. Looking at the stupidly steep side of the kiln now, it’s obvious it was never going to happen. When you’re a kid, though, you think that because you got up there on your little 50cc bike it should be no problem for this big three-wheeler, just as long as you get a good run at it.

Before long I was bombing it up there. The further up the mound you went, the steeper the gradient got and the more you needed to lean over the front to stop the bike rearing up; only the more you lean over the front, the less traction the back wheels have, and the steeper the gradient, the more traction you need. By the time I was three-quarters of the way up the side of the kiln I was on a 60 degree slope, leaning right over the front, and the rear wheels started to spin. And before I could say, ‘Oh fuck, what do I do?’ I found myself rolling slowly backwards wishing I’d stayed indoors and played Connect Four with my sister, like she’d asked. I was rolling, rolling, rolling, then suddenly it reared up and fell straight back, literally right on top of me.

Unlike my dad, however, I wasn’t flat on my back in the courtyard, I was upside down halfway up a steep hill with the trike not only on top of me but dug in. I was pinned down and I couldn’t move the thing, the angle of the slope making the trike even heavier and harder to budge. I started to panic, not least because I could smell petrol. Really, really strongly. And the engine was still running. I thought it could just be petrol coming out of the breather pipes, which isn’t such a big deal, but when I looked down to check I saw fuel pouring straight out of the tank. The petrol cap, which I was straddling, upside down, was leaking and the fluid was going all over my jeans. We’re talking about two Coke cans’ worth, all over my crotch.

I managed to turn the engine off, but I still couldn’t move it left or right. After several efforts I finally shifted it just enough to be able to drag myself out from under it. Without me underneath it, the trike destabilised, rolled over and then slid off down the hill, but I didn’t give a toss about it by this point because the petrol had soaked right through to my skin and was now burning me in the worst possible place. The pain was pain like you’ve never felt in your life. It was literally like having my bollocks marinated in battery acid. It fucking hurt. There was nothing for it, the jeans had to come off. It hurt so much that I took my pants off too.

I then ran down the hill, shouting, screaming and wailing, with nothing on below the waist, not a stitch, swinging my tackle in an effort to cool myself down, and across the field, straight past a family of ramblers in cagoules. God knows what they thought, but I wasn’t stopping to find out. When I reached the outside tap in the courtyard I turned it on and literally stood there under the water, like someone who’d been in the desert for a month and needed a drink. I just sat there with cold water running all over my little todger. No lasting damage was done, you’ll be pleased to know, but I dread to imagine what would have happened if I’d been under that trike much longer.

I never told anyone about my manhood’s close call. The trike was still in one piece so no one needed to know. If she’d found out, my mother would probably have stopped me going on the trike altogether. My dad, on the other hand, would probably have argued with her that at least I was learning lessons. Where my mother always wanted to protect, my dad was all for character building.

Sometimes I could see his logic, other times it just seemed cruel. I was always one of the quiet kids at school and was horrendously bullied for it. I used to get the shit kicked out of me all the time. At lunch I’d always get a good kicking, maybe have snow rubbed in my face if it was winter. I’d come home and my jacket would be ripped and I’d be covered in bruises. It got to the point where my mother was desperate to pull me out of school but my father wouldn’t hear of it. ‘No,’ he used to say, ‘he’ll stand on his own two feet and he’ll fight it. No son of mine’s going to run away. Let him face it.’ It’s a fine line between character building and character crushing, a very fine line.

My mother always wanted to keep me on the safe side of that line. Which is why I think she let me have the bikes in the first place, even though I couldn’t ride them on the road. I think she felt it was better that I got it out of my system in the relative safety of the farm rather than rush out at 16 and go crazy on the road. And she was right. When I was 16 I lost two very good friends in bike accidents. Neither had had motorbikes before. They turned 16, got a bike each, and were dead within twelve months.

Still, my mother would have been horrified if she’d known some of the things me and my mates got up to, especially on that Honda trike.

At the back of our house there was a hedge with gaps in it, and for some reason we thought it would be a really good idea to get my air rifle and try to shoot each other through the gaps as we rode past on the trike. One of us would be in the field with the air rifle, another would be on the trike on the other side of the hedge, riding backwards and forwards, being shot at. We were all rubbish shots and never managed to hit the rider, so really we just spent hours and hours riding up and down in a straight line and missing our target. I don’t know why, but me and my mates thought this was great fun. I know, I know, it’s not big and it’s not clever, and I’m not suggesting for a moment that it was a good idea. Kids, if you’re reading this, don’t do it. But it used to keep us out of Mum’s hair for hours. We were farmers’ kids, that’s what farmers’ kids do. Well, it’s what we did. Things are different in the country. It’s not like kids growing up in the city. We didn’t talk weird and play with knives – well, you know what I mean. Most importantly, though, no one ever got hurt when we were out and about. Not unless you count a few petrol burns in private places.

And the time we ran over Philip Schofield in my Fiat 126.

8 PHILIP SCHOFIELD IS DEFINITELY NOT A CHICKEN: THE FIAT 126 (#ulink_94f455b8-d893-5f77-b601-28658ad5ca4f)

My first experience of driving on four wheels came on a tractor. My dad had a big old Ferguson and he used to put me on his knee and let me steer; he would do the gears and the pedals. I was about eight at the time so my feet couldn’t reach. When I was ten I started driving it for real. It was a massive old thing and the steering was really heavy so I couldn’t drive it very far because it was such hard work. I’d drive it around the farm, but no more than maybe 400 yards before turning it round and coming back again. It was a proper old-fashioned model, with the tall exhaust pipe on the front, a flap on the top and tons of smoke belching out. Point is, by the time I got my first car, a little Fiat 126, at the age of twelve, I was already a pretty experienced motorist.

My dad figured that buying that car was cheaper than driving lessons, and he was right. He bought it off one of the staff at work for £40. It was completely knackered, they just wanted to get rid of it, and always being one for a bargain my dad jumped at it. It really was unfit for the roads, but it was great for whizzing around the farm. And because we lived in the middle of nowhere, my dad was always looking for ways to keep us, or more specifically me, entertained. After bikes and trikes, a car was the natural progression. (Well, it was either that or get a bigger bike, and the only thing to get after a Honda ATV70 trike would have been a Suzuki scrambler, which were quick little things – they’d do 90 miles an hour easy – and bound to get me into exactly the kind of trouble he was hoping to avoid.) He thought that if he didn’t focus my attention on an exciting piece of machinery I was going to go off and do all the stuff the other kids did, like, say, nicking things from empty farmhouses, being led astray by girls in uniforms, and messing about with air rifles. All the things I wouldn’t dream of doing. Never. Not me. Getting me a cheap banger was by far the safest option. More fool him.

The 126 was a tiny thing, just a bit bigger than the classic Fiat 500s, which I still love (I’ve actually got an original Abarth race model at home). It was dark blue with brown cloth interior – my childhood seems to have been cursed with brown cloth interiors – and it had a manual five-speed gearbox, no radio and a heater you couldn’t use because it reeked of something toxic, probably exhaust fumes, which made your eyes burn every time you turned it on. It was great. My dad taught me how to drive it in the courtyard round the back of the house, this time more successfully than his trike masterclass, and within minutes I was tearing around the fields. That thing provided me with hours and hours of fun.

And of course, once I’d mastered the five-speed gearbox, the clutch and driving in tractor ruts, all I needed to do was make it my own with a little customisation. So out came the masking tape and a couple of cans of yellow and red spray paint from Halfords and before you could say ‘pimp my ride’ my dark blue Fiat 126 had an unbelievably cool set of red and yellow flames coming off the front wheel arches and all the way down the side. Then, instead of a glass windscreen, it had chicken wire, which along with the blacked-out side windows (which you couldn’t actually see out of because I’d painted them with black spray paint – smart move) made it look like a proper rally car.

At least that was the official reason I gave for why the car suddenly had a chicken wire windscreen. The truth has been a closely guarded secret until now. My Fiat 126’s windscreen lost its glass when we ran over Philip Schofield (no, not that Philip Schofield!) in a game of chicken.

The rules of the game were simple, the same as all the hundreds of other games of chicken we’d played on our motorbikes and trikes over the years, the same as every game of chicken ever. One person stands in the middle of a field (in this case Philip) while someone else (in this case me and the rest of our mates in the car) drives at them. The person who bottles it and moves first is the chicken. Philip didn’t move. I’ve no idea why not, he just didn’t. There were four of us whizzing across that field in the Fiat, really hoofing it, doing a good 30 miles an hour. We were all looking at him, waiting for him to jump out of the way, and he was looking at us, waiting for us to swerve. We were looking at him and he was looking at us and the next thing, BANG!, we hit him. He hit the windscreen and went straight over the top. The 126 had a cloth sunroof which was open at the time, and I swear we all watched in horror as poor Philip flew over our heads. I remember his legs appeared to go past in slow motion. I looked in the rear-view mirror to see if I could see him, more importantly to see if I could see him moving. Everyone else in the car was shouting, ‘You’ve killed him, you’ve killed him!’ I did a handbrake turn and spun the car round just as Philip was getting up. I couldn’t believe it. Not only was he alive, he was in one piece. I seriously thought I’d ended his life.

The new priority suddenly became keeping him quiet. I couldn’t afford to have my mother finding out or that would have been it, we wouldn’t have had the car any more. In the end I made a pact with Philip. I told him that if he didn’t tell anyone we’d run him over I’d let him drive the car when he came round, which was a pretty big deal because I wouldn’t let anyone drive my car, so it seemed like fair compensation for running him over. Philip agreed and became the only person I ever allowed to drive that Fiat 126, although he could only drive it at certain times and in certain places as I didn’t want my mum or dad to see him at the wheel because they would have known straight away that something wasn’t quite right.

The windscreen wasn’t quite as easy to fix. The glass had cracked side to side where he’d hit it. One look at that and my mum would have wanted to know what we’d been up to, so I kicked the windscreen out, got some chicken wire from the farm and added ‘rally windows’ to my list of modifications.

Even after that, and with no windscreen, I used to drive that car like a lunatic over the fields. Just over the fields though, nowhere else. It was brilliant.

Not long after that my dad started taking me to Tockwith Aerodrome to teach me to drive properly. Tockwith was a disused old airfield near where we lived where parents would take their kids to learn the basics before going out on the road. It cost something like a fiver a go and you could drive round there all afternoon. Fittingly it’s now an approved go-karting school. Everyone else learning there was 17 or 18; I was there with my dad teaching me to mirror, signal, manoeuvre when I was 13.

We used to go over there in his Audi. We’d swap seats and he’d be straight back in advanced police driving instructor mode, telling me how to do it properly, and I mean properly. It wasn’t just all about the three-point turns and the reverse parking. He taught me to anticipate, to control my speed and brake with the gears, to go sideways, the lot. He must have been doing something right because I passed my test first time after only one hour-long lesson. I had intended to have more lessons, but I applied for my test as soon as I got my provisional licence; I had after all already been driving for five years by then. I got someone else’s cancellation, so one lesson immediately before my test was all there was time for. I turned 17 on 30 June and I passed my test on 7 July. So you see, my dad was right: at £40 my little Fiat 126 really was cheaper than driving lessons.

I’m not sure Philip Schofield was ever quite the same after his brush with the Fiat though.

9 FRANCE IN AN HGV (#ulink_b679bf8b-ee75-52a5-b13c-9d0f4f31d661)