По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

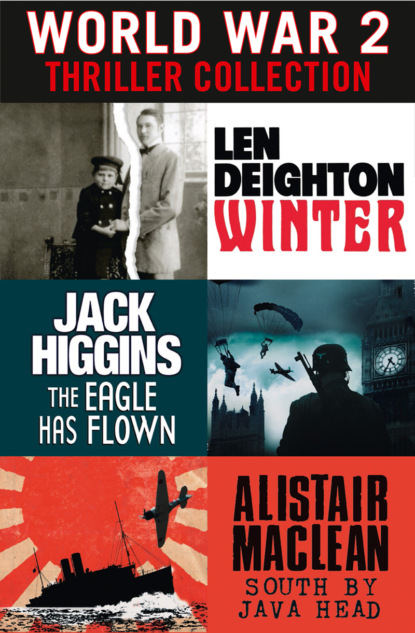

World War 2 Thriller Collection: Winter, The Eagle Has Flown, South by Java Head

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Auf Wiedersehen, Count Kupka.’

‘Auf Wiedersehen, my dear Winter.’ He clicked his heels and bowed.

Winter followed the servant downstairs. The club had only recently been connected to the telephone. Even now it was not possible for a caller to speak to the staff at the entrance desk; the facility whereby wives could inquire about their husbands’ presence in the club would not be a welcome innovation. The instrument was enshrined upon a large mahogany table in a room on the first floor. A servant was permanently assigned to answer it.

‘Winter here.’ He wanted to show both the caller and the servant that telephones were not such rarities in Berlin.

‘Winter? Professor Schneider speaking. A false alarm. These things happen. It could be two or three days.’

‘How is my wife?’

‘Fit and well. I have given her a mild sedative, and she will be asleep by now. I suggest you get a good night’s sleep and see her tomorrow morning.’

‘I think I will do that.’

‘Your baby will be born in 1900: a child of the new century.’

‘The new century will not begin until 1901. I would have thought an educated man like you would know that,’ said Winter, and replaced the earpiece on the hook. Already the bells were ringing. Every church in the city was showing the skills of its bellringers to welcome the new year. But in the kitchen a dog was whining loudly: the bells were hurting its ears. Dogs hate bells. So did Harald Winter.

‘What good jokes you make, Liebchen’

Martha Somló was beautiful. This petite, dark-haired, large-eyed daughter of a Jewish tailor was one of twelve children. The family had originally come from a small town in Rumania. Martha grew up in Hungary, but she arrived in Vienna alone, a sixteen-year-old orphan. She was working in a cigar shop when she first met Harald Winter. Within three weeks of that meeting he had installed her in an apartment near the Votivkirche. Now she was eighteen. She had a much grander place to live. She also had a lady’s maid, a hairdresser who came in every day, an account with a court dressmaker, some fine jewellery, and a small dog. But Harald Winter’s visits to Vienna were not frequent enough for her, and when he wasn’t with her she was dispirited and lonely.

Harald Winter’s mistress was no more than a small part of his curious and complex relationship with Vienna. He’d spent a lot of time in finding this wonderful apartment with its view of the Opera House and the Wiener Boulevard. From here she could watch ‘Sirk-Ecke’, a sacred meeting place for Vienna’s high society, who paraded up and down in their finest clothes every day except Sunday.

Once found, the apartment had been transformed into a showplace for Vienna’s newly formed ‘Secession’ art movement. A Klimt frieze went completely round the otherwise shiny black dining room, where the table and chairs were by Josef Hoffmann. The study, from writing desk to notepaper, was completely the work of Koloman Moser. Everywhere in the apartment there were examples of Art Nouveau. Martha Somló felt, with reason, that she was little more than a curator for an art museum. She hated everything about the apartment that Harald Winter had so painstakingly put together, but she was too astute to say so. Winter’s American wife, Veronica, had made no secret of her dislike for modern art, and the end result of that was the apartment in Kärntnerstrasse and Martha. If Martha made her true feelings known, there was little chance that Winter would get rid of his treasures; he’d get rid of her. It would be easier, quicker, and cheaper.

‘I love you, Harry,’ she said suddenly and without premeditation.

‘What was that?’ said Winter. He was in his red silk dressing gown, the one she’d chosen for him for his thirtieth birthday. It had been a wonderful day of shopping, followed by an extravagant party at Sachers. That was six months ago: now they hardly ever went anywhere together. Since his wife had become pregnant with this second child, he’d become more distant, and she worried that he was trying to find some way to tell her he didn’t want her any more. ‘I think I must be getting deaf; my father went deaf when very young.’

She went to him and threw her arms round his neck and kissed him. ‘Harry, you fool. You’re not going deaf; you’re the strongest, fittest man I ever met. I say I love you, Harry. Smile, Harry. Say you love me.’

‘Of course I love you, Martha.’ He kissed her.

‘A proper kiss, Harry. A kiss like the one you gave me when you arrived this afternoon hungering for me.’

‘Dear Martha, you’re a sweet girl.’

‘What’s wrong, Harry? You’re not yourself today. Is it something to do with the bank?’

He shook his head. Things were not too good at the bank, but he never discussed his business troubles with Martha and he never would. Women and business didn’t mix. Winter wasn’t entirely sure about women being admitted to universities. On that account he sometimes felt more at ease with women like Martha than with his own wife. Martha understood him so well.

‘Do you know who Count Kupka is?’

‘My God, Harry. You’re not in trouble with the secret police? Oh, dear God, no.’

‘He wants a favour from me, that’s all.’

She sat down and pulled him so that he sat with her on the sofa. He told her something about the conversation he’d had with Kupka.

‘And you found out what he wanted to know?’ She stroked his face tenderly. Then she looked at the leather document case that Winter had brought with him to the apartment. He rarely carried anything. Many times he’d told her that carrying cases, boxes, parcels, or packages was a task only for servants.

‘It’s not so easy,’ said Winter. She could see he wanted to talk about it. ‘My manager asked for collateral. This fellow owns land on the Obersalzberg. All the paperwork has been done to make the land the property of the bank if he defaults on the loan. I have now changed matters so that the loan has come from my personal account. Luckily the land deed is already made over to a nominee, so I get it in case of a default.’

‘Salzburg, Harry? Austria?’

‘Not Salzburg; the Obersalzberg. It’s a mountain a thousand metres high. It’s not in Austria: it’s just across the border, in Bavaria.’

‘In Germany?’

‘And that’s going to be another problem. I’m not sure it’s possible to turn everything over to Kupka.’

‘He’ll say you’re not cooperating,’ she said. She had heard of Kupka. What Jew in the whole of the empire had not heard of him. She was sick with fear at the mention of his name.

‘Kupka is a lawyer,’ said Winter confidently.

‘That’s like saying Attila the Hun was a cavalry officer,’ she said.

Winter laughed loudly and embraced her. ‘What good jokes you make, Liebchen. I’m tempted to tell Kupka that one.’

‘Don’t, Harry.’

‘You mustn’t be frightened, my darling. I am simply a means to an end in this matter.’

‘Just do what he says, Harry.’

‘But not yet, I think. Tonight I’m meeting this mysterious fellow Petzval at the Café Stoessl in Gumpendorfer Strasse. Damn him – I’ll get from him everything that Kupka won’t tell me.’

‘Remember he’s a relative of Kupka’s, and close to his wife.’

‘Rubbish,’ said Winter. ‘That was just a smokescreen to hide the true facts of the matter.’

‘Send someone,’ she suggested.

He smiled and went to the leather case he’d brought with him. From it he brought a small revolver and a soft leather holster with a strap that would fit under his coat.

‘If Kupka has his men there, a pistol won’t save you.’

‘Little worrier,’ he said affectionately and kissed her.

She held him very tight. How desperately she envied his wife; the children would always bind Harry to her in a way that nothing else could. If only Martha could give him a wonderful son.

1900

A plot of land on the Obersalzberg

It was dark by the time that Winter pushed through the revolving door of the Café Stoessl in the Gumpendorfer Strasse and looked around. The café was long and gloomy, lit by gaslights that hissed and popped. There were tables with pink marble tops and bentwood chairs and plants everywhere. He recognized some of the customers but gave no sign of it. They were not people that Winter would acknowledge: the usual crowd of would-be intellectuals, has-been politicians, and self-styled writers.