По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

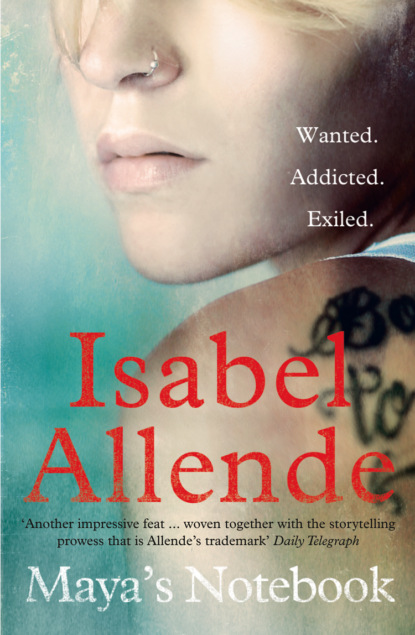

Maya’s Notebook

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Manuel Arias lives a mile—or a kilometer and a half, as they say here—from town, right on the sea, but there’s no access to his property by boat because of the rocks. His house is a good example of the region’s architecture, he told me with a note of pride in his voice. To me it looks like all the rest of the houses in town: it rests on pillars, and it’s made of wood. But he explained that the difference is that its pillars and rafters were carved with axes; it has “round-headed” shingles, much appreciated for their decorative value; and the timber used for it is Guaitecas cypress, once abundant in the region and now very rare. The cypresses of Chiloé can live for more than three thousand years, and are among the longest-lived trees in the world, after the baobabs of Africa and the sequoias of California.

The house has a high-ceilinged living room, where everything happens around the imposing black woodstove, which is used to heat the place and for cooking. There are two bedrooms—a medium-size one, which is Manuel’s, and a smaller one, mine—as well as a bathroom with a sink and a shower. There is not a single door inside the house, but the washroom has a striped wool blanket hanging across the threshold, for privacy. In the part of the main room used as the kitchen there’s a big table, a cupboard, and a deep crate with a lid to store potatoes, which in Chiloé are eaten at every meal; bunches of herbs, braids of chilies and garlic, long, dry pork sausages, and heavy iron pots and pans for cooking over wood fires all hang from the ceiling. A ladder leads up to the attic, where Manuel keeps most of his books and files. There are no paintings, photographs, or ornaments on the walls, nothing personal, only maps of the archipelago and a beautiful ship’s clock, its bronze dial set in mahogany, that looks like it was salvaged from the Titanic. Outside Manuel has improvised a primitive jacuzzi with a huge wooden barrel. The tools, firewood, charcoal, and drums of gasoline for the motorboat and the generator are kept in the shed out back.

My room is simple, like the rest of the house; there’s one narrow bed covered with a blanket similar to the washroom curtain, a chair, a dresser with three drawers, and a few nails in the wall to hang clothes on. More than enough for my possessions, which fit easily into my backpack. I like this austere and masculine atmosphere. The only worrying thing is Manuel Arias’s obsessive tidiness; I’m more relaxed.

The men put the refrigerator in its place, hooked it up to the gas, and then settled down to share a couple of bottles of wine and a salmon that Manuel had smoked the previous week in a metal drum with apple wood. Looking out at the sea from the window, they ate and drank in silence, speaking only to give an elaborate and ceremonious series of toasts: “Salud! Good health!” “May this drink bring you good health.” “And the same I wish to you.” “May you live many more years.” “May you attend my funeral.” Manuel gave me uncomfortable sidelong glances until I took him aside to tell him to calm down, I wasn’t planning on making a grab for the bottles. My grandmother had surely warned him, and he’d been planning to hide the liquor, but that would be absurd; the problem isn’t alcohol, it’s me.

Meanwhile Fahkeen and the cats were sizing each other up cautiously, dividing up the territory. The tabby is called Dumb-Cat, because the poor animal is stupid, and the ginger one is the Literati-Cat, because his favorite spot is on top of the computer; Manuel says he knows how to read.

The men finished the salmon and the wine, said good-bye, and left. I noticed that Manuel never even hinted at paying them, as he hadn’t either with the others who’d helped move the refrigerator before, but it would have been indiscreet of me to ask him about it.

I looked over Manuel’s office, composed of two desks, a filing cabinet, bookshelves, a modern computer with a double monitor, a fax, and a printer. There was an Internet connection, but he reminded me—as if I could forget—that I’m incommunicado. He added, defensively, that he has all his work on that computer and prefers that no one touch it.

“What do you do?” I asked him.

“I’m an anthropologist.”

“Anthropophagus?”

“I study people, I don’t eat them,” he told me.

“It was a joke, man. Anthropologists don’t have any raw material anymore; even the most savage tribesman has a cell phone and a television these days.”

“I don’t specialize in savages. I’m writing a book about the mythology of Chiloé.”

“They pay you for that?”

“Barely,” he admitted.

“It looks like you must be pretty poor.”

“Yes, but I live cheaply.”

“I wouldn’t want to be a burden on you,” I told him.

“You’re going to work to cover your expenses, Maya, that’s what your grandmother and I agreed. You can help me with the book, and in March you’ll work with Blanca at the school.”

“I should warn you: I’m very ignorant. I don’t know anything about anything.”

“What do you know how to do?”

“Bake cookies and bread, swim, play soccer, and write Samurai poems. You should see my vocabulary! I’m a human dictionary, but in English. I don’t think that’ll be much use to you.”

“We’ll see. The cookies sound promising.” And I think he hid a smile.

“Have you written other books?” I asked, yawning; the tiredness of the long trip and the five-hour time difference between California and Chile was weighing on me like a ton of bricks.

“Nothing that might make me famous,” he said pointing to several books on his desk: Dream Worlds of the Australian Aborigines, Initiation Rites Among the Tribes of the Orinoco, Mapuche Cosmogony in Southern Chile.

“According to my Nini, Chiloé is magical,” I told him.

“The whole world is magical, Maya,” he answered.

Manuel Arias assured me that the soul of his house is very ancient. My Nini also believes that houses have memories and feelings, she can sense the vibrations: she knows if the air of a place is charged with bad energy because misfortunes have happened there, or if the energy is positive. Her big house in Berkeley has a good soul. When we get it back, we’ll have to fix it up—it’s falling apart from old age—and then I plan to live in it till I die. I grew up there, on the top of a hill, with a view of San Francisco Bay that would be impressive if it weren’t blocked by two thriving pine trees. My Popo never allowed them to be pruned. He said that trees suffer when they’re mutilated and all the vegetation for a thousand meters around them suffers too, because everything is connected in the subsoil. It would be a crime to kill two pines to see a puddle of water that could just as easily be appreciated from the freeway.

The first Paul Ditson bought the house in 1948, the year the racial restriction for acquiring property in Berkeley was abolished. The Ditsons were the first black family in the neighborhood, and the only one for twenty years, until others began moving in. It was built in 1885 by a tycoon who made a lot of money in oranges. When he died he left his fortune to the university and his family in the dark. It was uninhabited for a long time and then passed from hand to hand, deteriorating a bit more with each transaction, until the Ditsons bought it. They were able to repair it because it had a strong framework and good foundations. After his parents died, my Popo bought his brothers’ shares and lived alone in that six-bedroom Victorian relic, crowned with an inexplicable bell tower, where he installed his telescope.

When Nidia and Andy Vidal arrived, he was only using the kitchen, the bathroom, and two other rooms; the rest he kept closed up. My Nini burst in like a hurricane of renovation, throwing knickknacks in the garbage, cleaning, and fumigating, but her ferocity in combating the havoc was not strong enough to conquer her husband’s endemic chaos. After many fights they made a deal that she could do what she liked with the house, as long as she respected his desk and the tower of the stars.

My Nini felt right in her element in Berkeley, that gritty, radical, extravagant city, with its mix of races and human pelts, with more geniuses and Nobel Prize winners than any other city on earth, saturated with noble causes, intolerant in its sanctimoniousness. My Nini was transformed: before she’d been a prudent and responsible young widow who tried to go unnoticed, but in Berkeley her true character emerged. She no longer had to dress as a chauffeur, like in Toronto, or succumb to social hypocrisy, like in Chile; no one knew her, she could reinvent herself. She adopted the aesthetic of the hippies, who languished on Telegraph Avenue selling their handicrafts surrounded by the aromas of incense and marijuana. She wore tunics, sandals, and beads from India, but she was very far from being a hippie: she worked, took on the responsibilities of running a house and raising a granddaughter, participated in the community, and I never saw her get high or chant in Sanskrit.

Scandalizing her neighbors, almost all of them her husband’s colleagues, with their dark, ivy-covered, vaguely British residences, my Nini painted the big Ditson house in the psychedelic colors inspired by San Francisco’s Castro Street, where gay people were starting to move in and remodel the old houses. Her violet and green walls, her yellow friezes and garlands of plaster flowers, provoked gossip and a couple of citations from the municipality, until the house was photographed for an architecture magazine, became a landmark for tourists in the city, and was soon being imitated by Pakistani restaurants, shops for young people, and artists’ studios.

My Nini also put her personal stamp on the interior decoration. She added her artistic touch to the ceremonial pieces of furniture, heavy clocks and horrendous paintings in gilt frames, acquired by the first Ditson: a profusion of lamps with fringes, frayed rugs, Turkish divans, and crocheted curtains. My room, painted mango, had a canopy over the bed made of Indian cotton edged with little mirrors and a flying dragon hanging from the center, which would have killed me if it ever fell and landed on me; on the walls she’d put up photographs of malnourished African children, so I could see how these unfortunate creatures were starving to death, while I refused to eat what I was given. According to my Popo, the dragon and the Biafran children were the cause of my insomnia and lack of appetite.

My guts have begun to suffer a frontal attack from Chilean bacteria. On my second day on this island I was doubled over in bed with stomach pains, and I’m still a little shivery, spending hours in front of the window with a hot water bottle on my belly. My grandmother would say I’m giving my soul time to catch up to me in Chiloé. She thinks jet travel is not advisable because the soul travels more slowly than the body, falls behind, and sometimes gets lost along the way; that must be the reason why pilots, like my dad, are never entirely present: they’re waiting for their soul, which is up in the clouds.

You can’t rent DVDs or video games here, and the only movies are the ones they show once a week at the school. For entertainment I have only Blanca Schnake’s fevered romance novels and books about Chiloé in Spanish, very useful for learning the language, but they’re hard for me to read. Manuel gave me a battery-operated flashlight that fits over the forehead like a miner’s lamp; that’s how we read when the electricity goes off. I can’t say very much about Chiloé, because I’ve barely left this house, but I could fill several pages about Manuel Arias, the cats, and the dog, who are now my family; Auntie Blanca, who shows up all the time on the pretext of visiting me, although it’s obvious that she comes to see Manuel; and Juanito Corrales, a boy who also comes every day to read with me and to play with Fahkeen. The dog’s very selective when it comes to company, but he puts up with the kid.

Yesterday I met Juanito’s grandmother. I hadn’t seen her before, because she was at the hospital in Castro, the capital of Chiloé, with her husband, who had a leg amputated in December and isn’t healing very well. Eduvigis Corrales is the color of terra-cotta, with a cheerful face crisscrossed with wrinkles, stocky and short legged, a typical Chilota. She wears her hair in a thin braid wrapped around her head and dresses like a missionary, with a thick skirt and lumberjack boots. She looks about sixty years old, but she’s only forty-five; people age quickly here and live a long time. She arrived with an iron pot, as heavy as a cannon, that she put on the stove to heat up, while she gave me a hasty speech, something about introducing herself with the proper respect; she was Eduvigis Corrales, the gentleman’s neighbor and cleaning lady. “Hey! What a beautiful big girl, this gringuita! Watch over her, Jesus! The gentleman was waiting for you, dear, like everybody else on the island, and I hope you like the little chicken with potatoes I made for you.” It wasn’t a local dialect, which is what I thought at first, but Spanish at a gallop. I deduced that Manuel Arias was the gentleman, although Eduvigis was talking about him in the third person, as if he weren’t there.

Eduvigis speaks to me, however, in the same bossy tone as my grandmother. This good woman comes to clean the house, takes the dirty laundry away and brings it all back clean, splits firewood with an ax so heavy I couldn’t even lift it, grows crops on her land, milks her cow, shears sheep, and knows how to slaughter pigs, but doesn’t go out fishing or to collect seafood because of her arthritis, she explained. She says her husband is not such a bad sort, not as bad as people in town think, but the diabetes really got him down, and since he lost his leg, he just wants to die. Of her five living children, only one is still at home, Azucena, who’s thirteen, and she also has her grandson Juanito, who’s ten, but looks younger “cuz he was born espirituado,” as she explained to me. This being espirituado might mean mental feebleness or that the one affected possesses more spirit than matter; in Juanito’s case it must be the second, because there’s nothing stupid about him.

Eduvigis lives on the produce of her small piece of land, what Manuel pays for her help, and the money her daughter, Juanito’s mother, who works at a salmon farm in the south of the Isla Grande, sends. In Chiloé the salmon-farming industry was the second largest in the world, after Norway’s, and boosted the region’s economy, but it contaminated the seabed, put the traditional fishermen out of business, and tore families apart. Now the industry is ruined, Manuel explained, because they put too many fish in the cages and gave them so many antibiotics that when they were attacked by a virus, they couldn’t be saved; their immune systems didn’t work anymore. There are twenty thousand unemployed from the salmon farms, most of them women, but Eduvigis’s daughter still has a job.

Soon we sat down to eat. As soon as she took the lid off the pot and the fragrance reached my nostrils, I was transported back to the kitchen of my childhood, in my grandparents’ house, and my eyes misted up with nostalgia. Eduvigis’s chicken stew was my first solid food for several days. This illness has been embarrassing; it was impossible to conceal vomiting and diarrhea in a house with no doors. I asked Manuel what had happened to the doors, and he replied that he preferred open spaces. I got sick from Blanca Schnake’s clams or the myrtle-berry pie, I’m sure. At first, Manuel pretended he didn’t hear the noises coming out of the washroom, but soon he had to drop the facade, because he saw me so weak. I heard him talking on his cell phone to Blanca to ask for instructions, and then he started making rice soup, changed my sheets, and brought me a hot water bottle. He keeps watch over me out of the corner of his eye without a word, but he’s alert to my needs. At my slightest attempt to thank him, he reacts with a grunt. He also phoned Liliana Treviño, the local nurse, a short, compact, young woman, with contagious laughter and an indomitable mane of curly hair, who gave me some enormous charcoal tablets, black, scratchy, and very hard to swallow. Seeing as they had absolutely no effect, Manuel got the greengrocer’s little cart to take me in to town to see a doctor.

On Thursdays the National Health Services boat, which travels around the islands, stops here. The doctor looked like a nearsighted fourteen-year-old kid who didn’t even need to shave yet, but it just took him a single glance to diagnose my condition: “You’ve got chilenitis, what foreigners get when they come to Chile. Nothing serious,” and he gave me a few pills in a twist of paper. Eduvigis made me an infusion of herbs, because she doesn’t trust remedies from the pharmacy, says they’re a shady deal from American corporations. I’ve been taking the infusion conscientiously, and it’s making me feel better. I like Eduvigis Corrales, she talks and talks like Auntie Blanca; the rest of the people around here are taciturn.

I told Juanito Corrales that my mother was a princess of Lapland, since he was curious about my family. Manuel was at his desk and didn’t make any comments, but after the boy left he told me that the Sami people, who live in Lapland, don’t have royalty. We’d just sat down at the table, a plate of sole with butter and cilantro for him and a clear broth for me. I explained that the thing about the Laplander princess had occurred to my Nini in a moment of inspiration when I was five and started noticing the mystery surrounding my mother. I remember we were in the kitchen, the coziest room in the house, baking cookies like we did every week for Mike O’Kelly’s delinquents and drug addicts. Mike is my Nini’s best friend, who is intent on achieving the impossible task of saving young people who’ve gone astray. He’s a real Irishman, Dublin-born, with skin so white, hair so black, and eyes so blue that my Popo nicknamed him Snow White, after that gullible girl that ate the poisoned apple in that Walt Disney movie. I’m not saying that O’Kelly is gullible; quite the contrary, he’s smart as can be: he’s the only one who can shut my Nini up. There was a Laplander princess in one of my books. I had a serious library at my disposal, because my Popo believed that culture entered by osmosis and it was better to start early, but my favorite books were fairy tales. According to my Popo, children’s stories are racist—how can it be that fairies don’t exist in Botswana or Guatemala?—but he never censored my reading, he would simply give his opinion with the aim of developing my capacity for critical thought. My Nini, on the other hand, never appreciated my critical thoughts and used to discourage them with smacks on the head.

In a picture of my family that I painted in kindergarten, I put my grandparents in full color in the center of the page, and way over on one side I added a fly—my dad’s plane—and a crown on the other representing my blue-blooded mother. In case there were any doubts, the next day I took my book, where the princess appeared in an ermine cape riding a white bear. The whole class laughed at me in unison. Later, back at home, I put the book in the oven with the corn pie, which is baked at 350º. After the firefighters left and the cloud of smoke began to lift, my grandmother bombarded me with the usual shouts of “You little shit!” while my Popo tried to rescue me before she ripped my head off. Between hiccups, with snot running down my face, I told my grandparents that at school they called me “the orphan of Lapland.” My Nini, in one of her sudden mood changes, squeezed me against her papaya breasts and assured me there was nothing orphaned about me, I had a father and grandparents, and the next swine who dared to insult me was going to have to deal with the Chilean mafia. This mafia was composed of her alone, but Mike O’Kelly and I were so afraid of her that we called my Nini Don Corleone.

My grandparents pulled me out of kindergarten and for a while taught me the basics of coloring and making worms out of Play-Doh at home, until my dad returned from one of his trips and decided that I needed to socialize with people my own age, not only with O’Kelly’s drug addicts, apathetic hippies, and the implacable feminists who were drawn to my grandmother. The new school was in two old houses joined by a second-floor bridge with a roof, an architectural challenge held aloft by the effect of its curvature, like cathedral domes, according to my Popo’s explanation, although I hadn’t asked. They taught using an Italian system of experimental education in which the students did whatever the fuck we wanted. The classrooms had no blackboards or desks, we sat on the floor, the teachers didn’t wear bras or shoes, and everyone learned at their own pace. My dad might have preferred a military academy, but he didn’t interfere with my grandparents’ decision, since it would be up to them to deal with my teachers and help with my homework.

“This kid’s retarded,” decided my Nini when she saw how slowly I was learning. Her vocabulary is peppered with politically unacceptable expressions, like retard, fatso, dwarf, hunchback, faggot, butch, chinkie-rike-eat-lice, and lots more that my grandfather tried to put down to the limitations of his wife’s English. She’s the only person in Berkeley who says “black” instead of “African American.” According to my Popo, I wasn’t deficient mentally, but rather overly imaginative, which is less serious, and time proved him right, because as soon as I learned my alphabet I began to read voraciously and to fill up notebooks with pretentious poems and an invented sad and bitter story of my life. I’d realized that in writing happiness is useless—without suffering there is no story—and I secretly savored being called an orphan; the only orphans on my radar were those from classic tales, and they were all very wretched.

My mother, Marta Otter, the improbable Laplander princess, disappeared into the Scandinavian mists before I could even catch her scent. I had a dozen photographs of her and a present she sent by mail for my fourth birthday, a mermaid sitting on a rock inside a glass ball, where it looked as if it was snowing when you shook it. That ball was my most precious treasure until I was eight, when it suddenly lost its sentimental value, but that’s another story.

I’m furious because my only valuable possession has disappeared, my civilized music, my iPod. I think Juanito Corrales took it. I didn’t want to make trouble for him, poor kid, but I had to tell Manuel, who didn’t think it was a big deal; he said Juanito’ll use it for a few days and then put it back where it was. That’s the way things work in Chiloé, it seems. Last Wednesday someone brought back an ax that had been taken without permission from the woodshed more than a week before. Manuel suspected he knew who had it, but it would have been an insult to ask for it back, since borrowing is one thing and theft is something else altogether. Chilotes, descendants of dignified indigenous people and haughty Spaniards, are proud. The man who had the ax gave no explanations, but brought a sack of potatoes as a gift, which he left on the patio before settling down with Manuel to drink chicha de manzana, a rustic apple cider, and watch the flight of seagulls from the porch. Something similar happened with a relative of the Corrales, who works on Isla Grande and came here to get married before Christmas. Eduvigis gave him the key to this house so that, in Manuel’s absence, while he was in Santiago, they could take his stereo system to liven up the wedding. When he came home, Manuel found to his surprise that his stereo had vanished, but instead of informing the carabineros, he waited patiently. There are no serious thieves on the island, and those who come from elsewhere would have a hard time getting away with something so bulky. A little while later Eduvigis recovered what her relative had borrowed and returned it, along with a basket of seafood. Manuel has his stereo back, so I guess I’ll see my iPod again.

Manuel prefers to be quiet, but he’s realized that the silence of this house might be excessive for a normal person and he makes efforts to chat with me. From my room, I heard him talking to Blanca Schnake in the kitchen. “Don’t be so gruff with the gringuita, Manuel. Can’t you see how lonely she is? You have to talk to her,” she advised him. “What do you want me to say to her, Blanca? She’s like a Martian,” he muttered, but he must have thought it over, because now instead of overwhelming me with academic lectures on anthropology, like he did at first, he asks about my past and so, bit by bit, we’re starting to exchange ideas and get to know each other.

My Spanish is very faltering, but his English is fluent, though with an Australian accent and a Chilean intonation. We agreed that I should practice, so we normally try to speak in Spanish, but we soon start to mix the two languages in the same sentence and end up in Spanglish. If we’re mad at each other, he speaks to me in clearly enunciated Spanish, to make himself understood, and I shout at him in street-gang English to scare him.

Manuel doesn’t talk about himself. The little I know about him I’ve guessed or heard from Auntie Blanca. There is something strange in his life. His past must be even more turbulent than mine, because many nights I’ve heard him moan and struggle in his sleep: “Get me out of here! Let me out!” Everything can be heard through these thin walls. My first impulse is to go and wake him up, but I don’t dare enter his room; the lack of doors forces me to be prudent. His nightmares invoke evil presences, the house seems to fill with demons. Even Fahkeen gets uneasy and trembles, right up against me in bed.

My work for Manuel Arias couldn’t be easier. It consists of transcribing his recordings of interviews and typing up his notes for the book. He’s so tidy that if I move an insignificant little piece of paper on his desk, the blood drains from his face. “You should feel very honored, Maya, because you’re the first and only person I’ve ever allowed to set foot in my office. I hope you won’t make me regret it,” he had the nerve to say to me, when I threw out last year’s calendar. I dug it out of the garbage intact, except for a few spaghetti stains, and stuck it up on the computer screen with chewing gum. He didn’t speak to me for twenty-six hours.