По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

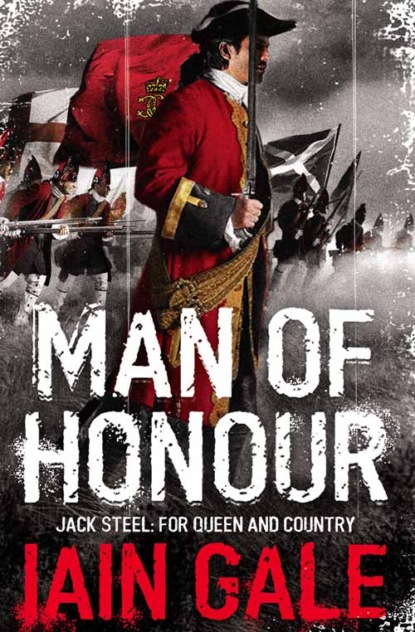

Jack Steel Adventure Series Books 1-3: Man of Honour, Rules of War, Brothers in Arms

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Ah, Mister Steel. I had quite forgotten you. I was just enlightening these young gentlemen as to the nature of our late engagement. Gentlemen, Mister Steel was also there at the Hill of the Bell. Although I am not certain as to in precisely which part of the fight he took part. Perhaps you would care to enlighten us, Mister Steel. Were you with the pioneers, or the baggage, perhaps?’

Steel said nothing.

Jennings grinned and took a sip from his glass of Moselle.

‘A fine wine this, d’you not think, Steel? Or perhaps you do not care for it. You would prefer something more robust. A bottle of Rhenish rotgut perhaps, or a nipperkin of molasses ale? I liberated this wine me’self from the cellars of the French commandant. You are most welcome to a glass, Steel. But do not feel obliged to accept. I do not suppose you are in a position to return my hospitality.’

It was too much.

‘I’m not sure that I properly understand you, Sir.’

‘You must do, Sir. For you forget, I am Adjutant of the regiment. I have sight of all the company accounts and unless you have rectified the matter, Mister Steel, your mess account remains unpaid from last month. And, as I recall, the month before that. Am I not right?’

Two of the subalterns laughed, briefly, then stopped, realizing that perhaps they had gone too far and that this was no longer a laughing matter. Then there was silence.

Jennings coughed and continued:

‘Of course, should you be in erm … difficulty, I would be only too happy to oblige with a small money order. For a reasonable consideration, of course.’

He smiled, narrowed his eyes, looked directly at Steel and took another sip of wine.

Steel stiffened with rage. Hansam, who had observed the conversation, now closed his eyes and was surprised by the calmness of his friend’s reply:

‘I have no need of your assistance, Major Jennings. I am informed that I shall profit from my share of the bounty due to my part in the assault party. And surely you too will benefit from that action. Or was I perhaps correct in assuming that you had actually taken no part in the fight?’

The party of subalterns let out an audible gasp. Jennings reddened, although what proportion was from embarrassment and what from indignation was not clear.

‘How dare you, Sir. You imply that I am a liar. Not merely that but a dissembling coward. Have a care how you trespass upon the reputation of a gentleman. As I am a reasonable fellow, I shall allow you to retract your accusation. Otherwise you must face my wrath, and the consequences.’

Steel pushed forward, knocking over the table and its contents. A wine bottle and two glasses smashed on the stone floor. The serving girl ran into the kitchens and the officers began to move away from the vortex of the argument. Steel spoke.

‘You will retract that comment, Sir.’

‘I think not, Mister Steel.’

‘You will retract that comment, Major Jennings, and your previous slur on my character, or pay for your insolence with your life. Although it will hardly be a fair fight. Nevertheless, you might provide me with a few moments’ sport. That is if you have the stomach for any fight. Which I very much doubt.’

Hansam spoke, quietly:

‘Jack. Do remember, duelling is not lawful. You will be court-martialled.’

Across the smoke-filled room the other officers had now stopped talking. But to those who knew the two men their confrontation came as no surprise. They knew that Jennings had long marked out Steel for just such an opportunity. And they, like Jennings, were puzzled by this curious, charismatic young man who had exchanged a prestigious commission in the Foot Guards – a position many of them would have killed for – for a lieutenancy in Farquharson’s unproven battalion of misfits.

It was plain to Jennings how he himself might profit from his association with his uncle’s regiment. He knew that money was to be made from the quartermasters’ books. Loss of stores; natural wastage. That sort of thing. Good cloth, ammunition and vittels fetched a good price on the open market and there were plenty in the regiment willing to help him for a few shillings, even if it did mean their risking the lash. And Jennings was sure that he would be able to keep himself out of harm’s way, as he had done yesterday. But people like Steel always seemed to be out to spoil his plans. Steel must be done away with and here was the opportunity, if somewhat sooner than he had expected. Jennings looked about the tavern and called to a red-coated officer.

‘Charles. A moment of your time.’

The man, a tall, lean individual with fine-boned features and a nervous twitch in the left side of his face, Steel recognized as Captain Charles Frampton of the regiment’s number two company. He knew him to be an ally of Jennings and watched as he now took his leave of his companions and walked across to the florid Major.

As the two men whispered, Hansam took Steel by the elbow.

‘Jack. You cannot do this. Not here. Not in public. If you must, then issue a challenge. Have it done in private. Of course, I shall second you. But not here. This is to invite disaster.’

Steel pulled free of his grasp. ‘Too late.’

Jennings had taken off his coat and handed it to the newcomer. ‘Mister Steel, you are acquainted with Charles Frampton. You have your own second?’

Steel nodded at the newcomer.

Hansam stepped forward.

‘Ah, Lieutenant Hansam. We are indeed honoured.’

Frampton muttered into Jennings’ ear: ‘Careful, Aubrey. I hear that he is a damned fine soldier.’

Jennings stiffened and, still smiling at Steel, spoke in a similar whisper to his second. ‘My dear Charles. Taking part in a few scraps in the Swedish war does not turn a man into a hero.’

‘They say, Aubrey, that he accounted for forty Russians single-handed at the battle of Narva. And that after Riga the King of Sweden himself presented him with a gold medal.’

‘Narva. Riga. What nonsense. Those names mean nothing. And now are we not allied to the Danes? Sweden’s enemies. I hardly think that Mister Steel will want to boast much of his relationship with the Swedish throne. Besides. Killing a few Russian savages? That’s not real war. Not the way gentlemen do battle.’

He drew from his cuff a crisp, white lace handkerchief and applied it gently to his delicate nose. ‘And that is precisely what I intend to demonstrate.’

Jennings walked forward.

‘Think now, Steel. Do you really want this end? Think on it. Do you really want to die in a tavern brawl. Were you aware perhaps that I had studied in London, under no less than the renowned Monsieur Besson? Perhaps you are familiar with him. He has taught the arme blanche in most of the courts of Europe.’

Steel did not reply. He merely drew his sword and assumed the en garde position.

Jennings instantly did the same. As Hansam hastened to Steel’s side, Jennings’ second walked to meet him. The two men shook hands and retired a few paces behind their friends.

The room had fallen silent now. Tables and chairs were pushed aside and most of the officers who had not already left began to make their exits into the street until only a small group of unwary subalterns remained. The staff too had long retreated behind the bar. The silence was broken suddenly by the sharp clang of metal on metal as Jennings tapped Steel’s blade.

Steel disengaged, circling Jennings’ sword with a deft flick of the wrist and made a slashing cut across the centre to unsettle his opponent. But Jennings had seen the move coming and side-stepped, returning to the en garde with the tip of his blade pointing directly at Steel’s side. He might have plunged it deep in, and the fact that he did not made it clear to Steel that he was only playing. Jennings spoke.

‘Oh come now, Steel. That was but a poke. I would not make use of such a thrust but with a ruffian. Have you nothing better to offer me?’

Steel raised his arm to the tierce position so that his blade was pointing directly downwards at Jennings, leaving his own body apparently unguarded. Jennings slapped at the blade with a clang of metal on metal and levelled his own sword, which came within an inch of Steel’s abdomen. Both men were sweating hard now. They pulled away for an instant, regaining their balance. Then circled and moved their blades around each other without touching. Steel’s sword made a marked contrast to Jennings’ lighter, standard issue infantry sword. But what it lacked in weight, the Major’s weapon made up in speed. Steel recovered his blade into the cavalry en garde, ready to slice at Jennings, but as he did so his opponent made a neat side-step and brought the tip of his own sword swiftly into contact with the Lieutenant’s arm, tearing the cloth of his shirt. Within seconds a thin red line had begun to darken the white cloth. Frampton spoke.

‘A hit to Major Jennings. First blood. Continue, gentlemen.’

Steel, appearing unaware of the damage to his arm, although actually in acute pain, took care to keep his blade as it was – pointing heavenward and poker-straight. If only, he thought, if only he will make one small error. Then I shall have him. He knew how easily his great blade could fall and with what force. How, given but a split-second his cut would sever Jennings’ sword arm and finish this business. But he could not find a way in. The man was too good. For all his foppishness and evident cowardice, it was clear that Jennings had not lied about his prowess with a sword. Steel began to walk to the right, encouraging his opponent to do the same until both men were circling slowly on the spot. Now. He thought. Now. If I can take the advantage. Just move for an instant to the left and then it will all be over. He prepared to make his move. Shifted the balance on his feet. Now. Now is the moment. The air hung heavy with anticipation. Now. It must be, now. But before Steel could strike the door of the tavern flew open with such force that its studded wooden surface banged hard against the wall.

The sudden noise broke the spell. Steel and Jennings stopped their dance of death and, frozen to the spot, turned their heads towards the light. Before they had a chance to renew the fight, the room had filled with a dozen redcoats armed with muskets. While two of them levelled their bayonets at the duellists, the others formed two lines through which another figure now entered the inn. A Colonel, a man in his late forties, clad in a neatly tailored dark blue coat, trimmed with red and gold lace. A Colonel on the British Staff.

The man strode forward purposefully towards Steel and Jennings, a grave expression on his face.

Hansam, moving quickly, pushed in behind Jennings to stand in front of the Colonel, attempting to block his view. He began to speak, quickly.