По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

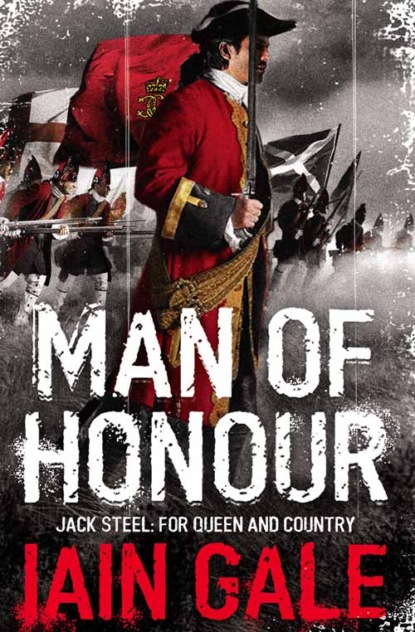

Jack Steel Adventure Series Books 1-3: Man of Honour, Rules of War, Brothers in Arms

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘You are quite set on laying waste to Bavaria?’

Marlborough looked down and tapped the red velvet-covered baton – the symbol of his rank – on the small, polished oak table which had been placed against the wall of the tent.

‘I shall dispatch men from this army to burn as many of the towns and villages of Bavaria as we find within reach. Just the houses mind you. We shall spare the woodlands and of course leave anything of the Elector’s property. Seeing that still standing can surely only help to turn his own people against him. And the people themselves shall be safe, I will not have any of them harmed. It is mere coercion, not rape, but it is the only way. We must force the Elector’s hand. It is of particular sadness to me in a country of such neat domestic husbandry as I have ever seen outside England.’

Hawkins shook his head. ‘If you are set on it, then I cannot divert your mind. But this is not warfare as you and I have known it these past twenty years. And if you really want to know my opinion it will not have the effect you believe. The Elector will not turn, whatever you do to his country. And be careful, Your Grace. I know soldiers as well as you do. For all your care of this army, Sir, it is still made up to a large extent of brigands and cut-throats. We shall have to keep a watch on them.’

Sensing how sombre the mood in the tent had now become, Hawkins added with a smile: ‘For I know how you hate anything that is not properly accounted for.’

Marlborough laughed. From outside the tent, above the general hubbub, they caught the sound of the drums and fifes of a regimental band striking up to keep the men in good spirits. ‘Lillibulero’. Marlborough smiled and began to drum his fingers on the table top. It was a favourite tune.

‘You still know how to divert me from my black moods, James. Thank God at least for that. But I am so tired. More tired, my friend than I can possibly remember.’ He rubbed hard at his forehead. Pressed his temples together.

‘My entire head aches to bursting. My blood is so terribly heated. I think that I shall call for the physician, presently. Did you know that I have had rhubarb and liquorice sent across from England. The Queen herself advised its use to Lady Sarah as a cure for the headache. But, even so, I am not fully persuaded. I am certain that by this evening I shall yet again be compelled to take some quinine. And you know how sick of the stomach that makes me. But even quinine cannot cure what really ails me.’

He looked into Hawkins’ eyes with a child’s gaze of hopeless yearning.

‘You know to what I refer. All my troubles, James. What times have come upon me. And who now remains with me in whom to place my trust? Poor Goors is dead. He, you know, was my chief help in moments such as this. Others too are gone. Tell me who, save you, old friend, who can I now turn to?’

Hawkins placed a gentle hand upon his Commander’s shoulder. ‘Do not despair, Sir. You are merely unsettled by your headaches. There is hope. As you say, you yet have me. And there is George Cadogan, Your Grace. He has ever been true. And Cardonell too.’

‘True, James. Quite true. Cadogan and Cardonell are a constant strength. Yet that is the measure of it. Just so. Two men and yourself, James. That is the sum of my family. How can I know who else to trust? How to know where my enemies may have placed their spies? God, how I long for this business to be over.’

Removing his wig to reveal his closely cropped hair, Marlborough draped it carefully over the stand made for the purpose that stood with his other personal effects on a small console table in the corner of the tent next to his camp-bed. Then he sat down at the table and, resting his elbows on its surface, buried his head in his hands.

Hawkins stared down at him and wondered at the vulnerability of this man in whom the nation, indeed half the civilized world had placed all its hope and trust.

Presently, the Duke raised his face and, pressing his hands, palms down hard against the table, flat on the polished wood, looked directly up at Hawkins.

‘We must prevail, James. We must beat the French.’

He paused in the epic silence of his words, knowing that, even with his old friend he must instantly dispel any suspicion that they might not be able to do so. Marlborough continued:

‘Oh yes, we shall beat them. That I do firmly believe. But first, I pray to God in heaven that your man Steel will be able to deliver me from the greater personal peril. Or else, truly James, we shall all of us be lost beyond redemption.’

Steel sat in the small tent and carefully inscribed the names of his dead men in the company roster with a neat, tutored script. His soldier-servant, Nate Thomas, sat just within the door flap polishing his master’s boots.

Nate liked Mister Steel. Cared for him more than most of the officers in this army in which any gentleman might purchase a command but where precious few officers were gentlemen. Steel he knew to be a fair man. A man who, if he was cool at times, would always give reward where it was due. And he was a real soldier too. Not some trumped-up popinjay like so many of those who took it upon themselves to give commands. All the same, thought Nate, as he spat on the toe of Steel’s boot before buffing it again, best to give him a proper shine today. For whatever might be Steel’s odd habits, and although he was inclined to behave more like a sergeant at times, Nate knew that he must not have his officer looking untidy on battalion parade. He spat again and began to rub the polish into the leather with a round, even motion, decreasing the size of the circles to produce a glass-like finish. He was staring proudly at his handiwork when Henry Hansam appeared in the entrance. He looked down at the soldier-servant.

‘Hard at it, Nate? Making a good job of it. In truth, though, I shouldn’t bother if I were you. You know that Mister Steel will have them filthy again two minutes after you’ve finished.’

He turned to his friend. ‘Jack. We have a new travelling companion. Allow me to present Lieutenant Thomas Williams, lately arrived from England to join the regiment. More specifically to join our own company. I give you, our new Ensign.’

With a theatrical flourish, Hansam stepped into the two-man tent, holding open the flap so that his companion might enter. The newcomer was a young officer of perhaps 16 years old, with that distinctive, wiry build that came with the starvation diet prescribed by one of England’s finest private schools and a complexion that most readily reminded Steel of ripe strawberries. What most marked Williams out however, was the even brighter hue of his new scarlet coat, as yet unblemished to the drab brick-red worn by the other officers and men of the army, dulled by the dust and mud of campaigning. His crossbelt was whitened to perfection, his cross-plate, sword hilt and scabbard shone fresh from the foundry and his hair was hidden beneath the rich locks of a clean, new full-bottomed chestnut-brown wig that must have cost the best part of a sergeant’s annual pay. In short, thought Steel, the boy was perfect cannon fodder.

Steel smiled and rose to greet the new arrival.

‘Mister Williams. Or might I say Thomas? Or perhaps you prefer Tom? You must know at once, Tom, that we stand on no great formality in this company.’

‘Thank you, Sir. My parents do call me Thomas, but you may call me Tom, if you wish, Sir.’

He was touched by this unusual officer’s apparent interest, and surprised. It was one of the rare instances he had found since his arrival in this army of what just might prove to be real friendship.

The younger son of a gentleman farmer from Wiltshire, Thomas Williams, with his lack of ability to absorb either the classics or the Bible and his tendency to colour and stutter when the centre of attention, had seemed from the first an unlikely candidate for the church and so his father had purchased him a commission in Farquharson’s Foot. Perhaps in a couple of years’ time, if Thomas acquitted himself well, Mr Williams senior would find the additional £300 to raise his son to a full Lieutenancy. Perhaps the army might be the making of him. For the present, however, Tom found himself on the lowest rung of the officer hierarchy and his new comrades had lost no time in letting him know it. Here though, in this curious-looking, strikingly handsome Lieutenant of Grenadiers, with his strange clothes and the unorthodox hair, Thomas Williams sensed that he might have found a kindred spirit, or perhaps at least a guardian angel. He realized that Steel was looking at him very closely.

‘Have we met?’

Steel stared hard at Williams’ eyes. Looked at the long slant of his nose, the slightly weak chin and tried to place him. Eventually it came. ‘Yes. I believe we have. I do know you now. You were with Jennings. At the tavern.’

The boy blushed and looked down at his gleaming shoes. Grasping nervously at his sword knot, Tom said nothing. Then thought the better of it:

‘I wasn’t exactly “with” Major Jennings, Sir.’

Steel smiled. Perhaps he had underestimated the lad after all. He knew how defend himself in an impossible position.

‘Yes. That’s good. Well said. And I assume, Tom, that, even if you were not “with him”, you knew better than to believe any of his arrogant twaddle?’

Williams looked up, uncertain as to how to take this or how to respond. Was it yet another example of the sort of mess-hall ribaldry to which he was fast becoming accustomed? Were they trying to make him appear a fool yet again, as he had so often been caught out at Eton and only recently, on his first week in the army when a sergeant-major at the depot in England had quite deliberately put him out of step when on parade.

‘I … I don’t quite understand, Sir. I thought that Major Jennings was considered a hero. He said that …’

Steel exclaimed and cut in: ‘You will hear Major Jennings say many things, Tom. And I dare say it is possible that some of them may well be true. So, if you choose to believe that he is the perfect martial hero he would have you think him, then you must consider that is precisely what our Major Jennings is. He is a hero as drawn on stage by the great Colley Cibber himself, or Sir John Vanbrugh. As perfect a hero as you or I might be likely to see treading the boards at Drury Lane or Dorset Fields on any night of the week, for two shillings.’

Williams frowned.

Hansam chuckled. ‘Now, Jack. Don’t tease the lad.’

Steel nodded. ‘I was forgetting myself. Hero or not, Tom, Major Jennings is a soldier nevertheless, and he will march with us and serve with us beneath the colours and he will stand with us before the shot on the field of battle and take his chances against the French just as we do.’

At the mention of battle Williams turned pale, then smiled, wanly. Steel, noticing his apprehension, attempted to ease the moment by pretending to brush something off his coat.

‘Wait. There. Restored to glory. And there is more to soldiering than battle, eh Henry? What think you to the army, Tom?’

‘I … I think it must be a very grand life, Sir. I think … that I shall very much like being a soldier.’

Both the Lieutenants laughed. Steel clapped Williams on the back.

‘And I think that perhaps I’ll ask you that question again shortly after your first battle. Then we’ll see how you reply, Tom, eh? Now, come. Time presses. Permit us to stand you a dish of tea, or something stronger if you will, in what passes for the present for our mess. Nate. My boots.’

After Steel had pulled on the shining boots and finished adjusting the other elements of his dress, the three men walked out of the tent. Before them, reflecting the pale sunshine, lay a mass of similar white tents, laid out in symmetrical lines and grids: the entire British army encamped under canvas in its temporary home. It was as if, Steel thought, a small English town had been transported to the heart of Bavaria. Along the alleyways that ran between the rows of tents bewigged officers strolled in conversation while among them dozens of children – the offspring of camp followers – ran and played, sometimes pursued by their desperate mothers. Other women sat nursing babies or were busy washing and steaming the lice-infested clothes of husbands and families or cooking suspicious-looking rations in great iron pots. Soldiers sat beside their tents darning their uniforms and attending to minor wounds and the blisters and sores which inevitably followed from a long march. In separate lines, tradesmen and craftspeople sat before their own tents making good the accoutrements required to keep 30,000 men in a battle-ready state. And with this vision of industry and idleness came the unmistakable noise and aroma of camp life. The staccato clack of metal on metal, the whinnying of the horses, the shrieks of the children, sharp against an undercurrent of chatter and music and rising above it all the not altogether unpleasant stench of food, sweat, horses and humanity. Steel watched as carts filled with provisions rumbled past the lines while others standing ready for the wounded from whatever battle was next to come, were cleaned as best they could by the sutlers of the blood and gore left by their previous unfortunate occupants.

It was a scene being enacted throughout the south German states that morning, and across the French border, Steel knew, in the camp of every army: British, French, Hanoverian, Prussian, Bavarian and the rest. But here, he thought, something was subtly different. Here, he knew that before the tent lines had been laid, the site had been carefully chosen by keen-eyed civilian commissaries sent out by Marlborough himself. And close behind them followed the army: always setting off early in the morning, at sunrise – five o’clock or before – and halting shortly after midday, thus avoiding the greatest heat and making camp so that the night’s rest gave the men the illusion of a full day’s halt. Such was the care that the General took with his army, thought Steel. He knew too that the food and provisions now so evidently on display had been carefully stockpiled to provide for just such an encampment.

This was the new army. Marlborough’s army. An army that made the old sweats mutter in amazement. For here was organization of a type never before seen in a British army on foreign soil. It was Marlborough who had made this army. Had fashioned it from the ragtag rabble that had emerged from the chaos of King William’s Glorious Revolution and brought it through the Irish wars to this great campaign. It was true that back in London, the Duke still had his enemies who even now might be plotting his removal. But here on the march, with the army, ‘Corporal John’ was God. But he was also a soldier and a man, his vulnerable mortality no different from any who filled the ranks of his army. That was the reason the soldiers would fight for him. Would die for him – a hero’s death if they were lucky. That was why they would march wherever he took them. To whatever lay over the next hill. To glory. And so, as the women cooked and sewed and the money changed hands, and the children played and the wounded died, the majority of the soldiers wondered how long they might count on being able to rest and how many more dawns they might see.

Hansam broke Steel’s reverie. ‘I see that we have our Prussian friends with us now.’

Steel too had noticed the arrival of the long marching column as it snaked its way past the lines of the British encampment. The distinctive dark blue coats of the Hanoverian and Prussian infantry, their tall Grenadiers evident in their own profusion of elegant, elaborately laced caps. These were their allies, marching to join Marlborough’s red caterpillar. There must be, he supposed, several thousand of them. Perhaps ten battalions.