По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

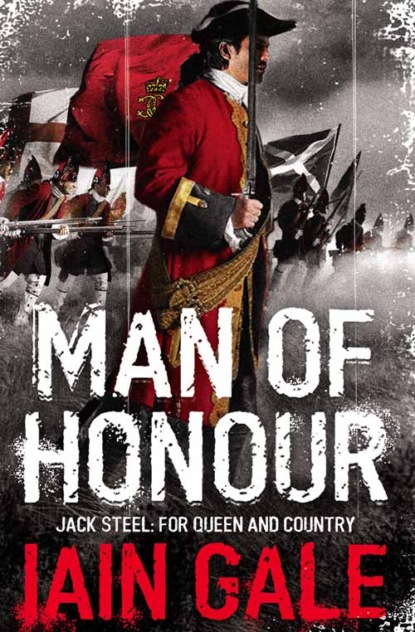

Jack Steel Adventure Series Books 1-3: Man of Honour, Rules of War, Brothers in Arms

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Steel hooked his hand beneath the sling of the gun and moved to let it fall to the ground. Just as it seemed that he was about to drop it though, he grasped the weapon by the barrel, and dipping down beneath the bayonet and musket, swung it up and drove it, butt first, with all his strength deep into Stringer’s groin. The man yelped in agony, dropped his musket and fell to the ground, screaming and clutching at his genitals. Steel, still holding the gun, straightened up, but Jennings was quick.

Thinking fast, the Major made a copy-book lunge at Steel’s side and struck home. He felt the blade slide into flesh and quickly withdrew it. Steel let out a hollow groan and turned, clutching at his side.

‘Tut tut. Brawling with a senior officer, Mister Steel? You’ll never find promotion that way. En garde? Oh, you are unarmed. Well, as you will then.’

Steel swung out wildly with the gun, but Jennings hardly had to move to avoid it. He lunged at Steel and cut into thigh, a few inches above the knee. The pain tore through the Lieutenant. Steel looked about for his sword and saw it, lying just a few feet away. If he could just get to it, somehow. Hurling the gun at Jennings, he reached wildly for the sword and grabbed at the hilt but before he could make contact, Jennings was on him again. Steel felt the burning stab as the tip of the sword just nicked his back. He turned and, his eyes filled with rage and pain, threw himself, weaponless upon the Major, wrenching his sword by the blade from his hand and in the process cutting his own down to the bone. Jennings, taken completely by surprise, dropped the sword and saw that Steel still had it by the blade.

To Steel’s right, close to where the Sergeant was still writhing in pain on the ground, Jennings saw Stringer’s fallen musket. In an instant Jennings was on it and, as Steel paused to move the sword hilt into his right arm, he brought the heavy wooden butt crashing down like a club upon the Lieutenant’s skull, with a sickening crack. Steel’s legs gave way and he slumped to the cobbles. He fell on to his knees, his back quite rigid and, as his eyes filled with a red haze, collapsed upon his face. Jennings, breathless, stood over him, the musket still raised in his hands. No, he thought. He would not beat the man’s brains out. Nor would he spit him on the bayonet. He would finish him like a gentleman. But first. He dropped the weapon to the ground and, crouching down, reached beneath Steel’s heavy body. He delved into the inner recesses of his coat and at last his fingers closed around a small square object. Smiling he withdrew his hand and looked at the package. It was tied with twine around brown paper. He eased the string to one side and read the first, faded page.

‘Your Majesty,

You cannot know how my heart yearns for your return and how all Britain shall rejoice when once again our land is restored to its rightful monarch …’

Looking further down the small sheet Jennings was able to discern the signature:

‘Your most faithful servant,

John Churchill.’

Jennings clasped the package to his chest before placing it deep within a pocket of his waistcoat. Then, still grinning, he stooped again to collect his own sword from where it lay beside Steel’s limp hand. Now, one thrust and the world would be rid forever of this annoying upstart. Taking his time, Jennings stood over Steel’s body, lining up his blade with the left side of his back, just at the point where the heart would be. He raised the weapon to strike. Now, and it would be finished.

‘Sir! Major Jennings, Sir. What are you doing?’

Williams ran from the alleyway and stopped in his tracks. Jennings advanced upon him, his sword at the ready. The boy raised his own weapon but not before Jennings had time to lunge and slash his thigh with the tip of the blade. Williams yelped in pain but kept his guard.

The two men began to circle one another. Jennings whispered:

‘Steel’s dead, boy. He betrayed his country. Now put down your sword and we’ll say no more of it.’

Williams noticed Stringer now and realized that Jennings might not be telling the whole truth.

‘I don’t believe you, Sir. You killed him.’

‘I killed a traitor.’

‘Mister Steel was an honourable man, Sir. He would never betray us.’

Jennings sighed.

‘Ah well. I gave you your chance. Have you ever fought anyone before boy? One to one? Have you?’

Williams said nothing. But, to Jennings’ surprise, he lunged and caught the Major momentarily off guard. The tip of his sword glanced against Jennings’ left arm and drew blood.

‘So. You’ve got spirit. I’ll give you that. But spirit ain’t enough for me, boy.’

Jennings lunged again and, as if he was using the boy to demonstrate his skill, as a fencing master might use a dummy, touched the Ensign less than an inch away from his previous wound.

The pain seared red-hot through Williams’ leg and he was conscious of the fresh, warm blood dripping on to his reddened stocking. God, thought Williams, but Jennings is good at this game. So much for his costly fencing lessons at Eton. What use now the classical moves on which he had spent so much time? This fighting was fast and brutal. No finesse here. Just kill or be killed. And at present, Williams guessed, he would not be the one who would be walking away with his life. He glanced at Steel’s motionless form.

Jennings broke the silence.

‘He’s dead, boy. Quite dead. Come on, you’re not scared, surely? That won’t make you a soldier. Soldiers are brave, Mister Williams. But you’re not brave are you? You’re scared. Daddy wanted you to join us. You were good for nothing else. But you’ll never make a soldier. You haven’t the guts for it. Get out now, before it’s too late. Before you’re spitted by some Frog.’

He laughed to himself.

‘Oh dear. I forgot. It’s too late already.’

On the last word, he lunged and made contact with Williams’ right forearm. The Ensign staggered backwards and slipping on the cobbles, slick with Steel’s blood, lost his balance and went crashing to the ground, hitting his head on the sharp edge of the wide stone windowsill. He slumped to unconsciousness, trailing blood down the wall behind him. Stringer had managed to get to his feet now and was hobbling about, doubled over with pain.

Jennings looked at the Sergeant for a moment, then back at Williams and Steel, deciding which of the fallen men he should make sure of first. There was no choice. He crossed to where Steel lay and was about to raise his sword again when Stringer, looking down the alleyway, pointed and called out in a hoarse voice:

‘Sir.’

Jennings looked round just as the tall figures of two of Steel’s Grenadiers emerged into the street. He clutched at his arm and pressed on the cut, making sure they would see the blood seeping through his fingers. He feigned pain and screamed towards the two redcoats:

‘Hurry men. The French are behind us. I’ve been hit. Mister Steel’s dead.’

The Grenadiers rushed past him and Jennings ran up the street towards the main square. It was deserted, save for the carriage. Jennings ran across to it and moved to the front. There were two horses, both built for strength rather than speed. Jennings began to unbuckle the harness of that closest to him and then, leaving her in the shafts, turned back towards the door of the coach. The money, Kretzmer’s payment for the flour and whatever he had from Steel, confiscated after his crime, had been placed in a strongbox on the floor of the carriage. It could not go to waste. Jennings pulled himself up into the compartment, opened the lid of the box and withdrew the two leather purses. He looped the strings of the two heavy bags around his belt and turned towards the door. Stepping down from the carriage, he began to lead the dray horse from the shafts. He was preparing to mount her when, from close behind him he heard an unmistakeable noise. It was the sound of a musket’s hammer being cocked. Instinctively Jennings began to turn and as he did so, he saw a red-coated figure with a musket levelled directly towards him. Dan Cussiter was standing a few paces away from the door of the coach. The Private stared at him with venomous, vengeful eyes, his mouth curled in a tight smile.

‘Now, boy, don’t be hasty. I can explain everything.’

Cussiter said nothing. He tucked the musket deeper into his shoulder and Jennings knew that it was ready to fire. All he could hear now was the beating of his own heart.

‘Don’t be foolish, boy. You know what punishment feels like now. You’ve felt the cat. Imagine what they’ll give you for killing an officer. Put down the gun. Be sensible. I’ll speak for you.’

He extended his hand. Cussiter’s finger played with the trigger. His eye looked straight down the barrel of the musket, straight at Jennings’ forehead. He began to squeeze and Jennings waited for the flash. It came but as he closed his eyes and flinched away he sensed no more than a slight burning sensation on his head, as if he had been touched by a sudden, fast breath of hot wind. Opening his eyes he saw that the puff of smoke had gone high into the air and with it the musket ball, which had evidently done no more than nick his head and part his wig. He looked back at Cussiter and saw him sprawled on the ground, locked in a desperate struggle with Stringer. Evidently the Sergeant had hurled himself at the man at the moment his finger had pulled the trigger.

Jennings did not wait. Stringer might have saved his life, but he had no time for thanks. The Sergeant was no longer necessary to his plans. With no time to take the horse, he turned and he ran as fast as he could for the corner of the nearest house. Behind him the space had filled with soldiers. He did not look back. Ahead of him, at a crossroads of back alleys, a dead French hussar lay sprawled on the ground, his hand still tangled in the reins of a bay mare who stood close by chewing at a patch of scrub. Not wasting a moment, Jennings ran to the horse, snatched up the reins and pulled them from the dead man’s hand. Then he was up and in the saddle. He whipped the animal quickly into a canter and then a gallop and drove her fast through the narrow streets, and then down and over the bloody bridge and out into the fields. He was exultant. He had the papers. The papers that would bring down Marlborough and guarantee his own passage to untold influence and prosperity. But before any of that could happen, he would have to carry them to safety. And after what he had just done, he knew that at this moment, safety lay in only one direction. Aubrey Jennings pressed his spurs deep into the horse’s flanks and rode as fast as he could towards the French.

Steel coughed blood and felt a loose tooth in his mouth. He spat it on to the cobbles. His head felt as if someone had laid about it with a hammer. He put his hand up to touch it and felt the blood. He coughed again and retched. Looking up, he could see Williams getting to his feet. His face was covered with rivulets of blood and he was standing as groggy as a drunk. One of the Grenadiers, Mackay, placed a hand beneath the Lieutenant’s arm and Steel tried to stand. As he put the weight on his right leg a searing pain shot through his calf. He looked down and saw for the first time the extent of the damage done by Jennings’ blade.

‘Bugger.’

He looked at Mackay.

‘Where is he?’

‘Who, Sir?’

‘Major Jennings, man. Did you get him?’

‘He’s gone back to the fight, Sir. Told us the Frenchies had killed you.’

‘Like hell he has. Major Jennings is a traitor.’

So, Jennings had escaped. Steel panicked. He reached inside his coat for the packet and, as he had known he would, felt nothing. He had known Jennings to be bad, but a traitor on this scale? It had not entered his wildest imaginings. Through the mist of his agonizing headache he heard the sounds of battle. Christ almighty. They were still fighting the French. It began to come back to him.

‘Williams. Are you all right?’