По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

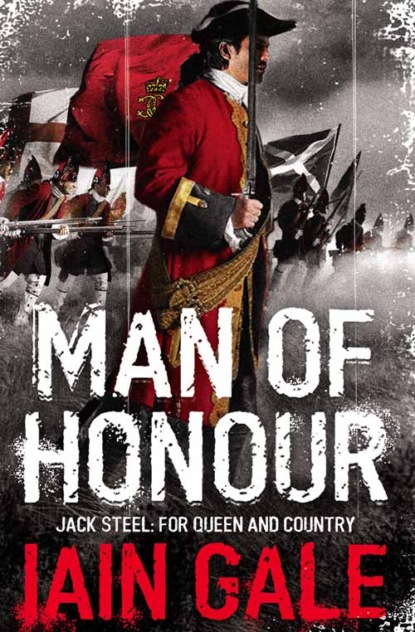

Jack Steel Adventure Series Books 1-3: Man of Honour, Rules of War, Brothers in Arms

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Steady. Steady.’

Then it was time.

‘Fire.’

The air became a cloud of white smoke and ahead of them, just at the moment that the three leading hussars left the confines of the bridge, he saw eight or even ten of their number crash down in a heap of men and horses.

‘Right. Retire. All of you. Run.’

Steel began to walk backwards, still gazing at the carnage on the bridge. Some of his men, the old sweats, did likewise but most of them were already running hell for leather back up the little street.

And then he was with them, running too, as fast as he could go.

Steel knew that it would take a few moments for the cavalry to disentangle themselves from the dead and dying. But he knew too that once they were clear, he and his men would be defenceless until they reached the reserve at the top of the hill.

Steel cast a nervous look back over his shoulder and saw, emerging out of the clearing smoke, the distinctive shapes of the hussars. And now they were free to charge.

‘Run you buggers. Run.’

His boots slithered up the slippery cobbles, his heart thumping against his chest. He knew that a few of his men would go down. But this was their only hope. Ahead he could see now the three ranks of redcoats. He raised his hand, motioning them to the side.

With perfect precision they parted just in time to admit the remainder of the men in front of him. Steel was ten feet away from them now. From behind he heard a scream as one of the Grenadiers fell beneath a hussar’s bloody sabre. The line had to close up or else they would all be lost. He raised his hand again, signalling them to move together. Unquestioning, the men did as ordered and he was caught between the crash of approaching hoofbeats and a wall of bayonets and muskets. He dared not look round again, but he could feel the hot breath of a horse on his back. Six feet to go now. Five. With an almighty effort, Steel threw himself at the line of redcoats and, sensing the presence of something cutting the air immediately behind his neck, slid on his back across the cobbles before crashing into the feet of two of the front-rank men. At that exact instant, above his head, the world became a storm of shot as the redcoats opened up. Steel pressed his head into the stones and prayed.

Still lying down, he turned his face towards where the cavalry had been. As the smoke cleared he saw six of the horsemen and four horses lying dead and dying in the street. He knew that it wasn’t enough. Behind the shattered, blue-coated bodies he could see a block of hussars, riding knee to knee, advancing steadily towards him. The volley had merely skimmed the top of the column. They had not even bothered to re-form. Their commander had sent them forward in waves. The first had been annihilated, but here was the second. There might be time for one more volley. But then what? How could so few infantry resist? He clambered to his feet and edged to the rear rank looking around at the redcoats. He saw Slaughter, Cussiter, Taylor, Tarling, Hopkins and Tom Williams. Good. Though he wondered which poor devils had been left out there on the cobbles with the dead hussars. And where in God’s name was Jennings? Stringer too had disappeared. Steel was damned if either man was going to be spared what looked as if it might be their last fight. He found Williams.

‘Tom, go and see if you can find Major Jennings and Sarn’t Stringer. Look everywhere. They’re probably somewhere near the square. Hurry.’

He turned to Slaughter.

‘Reload, Sarn’t. How many rounds a man do we have?’

‘Couldn’t say, Sir, but it can’t be many. There’s always the grenades.’

‘No. The cobbles would be blown to blazes. We’d kill as many of our own men as theirs. It’s bullets this time, Jacob. And bayonets. Let’s see how many we can take with us.’

Steel could see the hussars coming on again. His plan had worked but it had not been enough. He wondered whether Williams had found Jennings and Stringer. Whether they would reach him before the cavalry rode down the redcoats and began their butchery or whether the three officers might yet escape. Glancing across the square he saw the empty carriage and thought of Louisa. What would happen to her? He should have sent her away. But how? Too late now for that. He prayed that the French hussars would be more merciful than their Grenadiers. He turned to Slaughter and smiled. He was ready for it now. Listening for the hooves on the cobbles, for the battle cries that would come as the cavalry urged themselves on towards the guns and the bayonets, Steel turned to the redcoats:

‘Make ready.’

Down the street the hussars still came on, boot to boot.

‘Present.’

The cavalry were trotting at them now. He could see their faces and their piercing eyes. Heard the sergeants calling out commands in French. Pushing them on. They were packed too tight for a canter, but Steel knew that their sheer weight would be enough to push them into the infantry. The line of muskets held its aim on the advancing cavalry. Slaughter hissed at them:

‘Steady. Wait for the command.’

Thirty paces out. Twenty.

‘Fire!’

Steel yelled the word and as he did, squeezed the trigger of his own weapon. The volley filled the narrow street, half-deafening the infantry and covering the scene in thick white smoke. Steel peered towards the enemy.

‘Prepare to receive cavalry.’

The volley had slowed the riders but he was sure that they would come on, regardless. Suddenly, from the white mist figures began to appear. To his left three hussars had managed to negotiate the piles of dead and broken men and horses and connected with the line. The first took a bayonet in the thigh and hacked down at his assailant, who ducked and, retrieving his bloodied blade, thrust it again and this time sent it clean into the cavalryman’s unprotected side. The man clutched at the weapon and hurled himself from the saddle only to impale himself further. Next to him another hussar had had better success, parrying the thrust of one of Jennings’ men and swiping down with his blade to flense off half of the man’s face. Steel pushed aside the dying musketeer and before the Frenchman could defend himself, made a great sweeping cut with the broadsword, taking the tip of his blade and three inches of steel through the man’s side and belly. The man dropped his sword and clutched at the awful wound. He tried to turn his horse and was brought down by a shot, fired from the rear rank. More figures were appearing through the smoke now. A voice from his rear made him turn. It was Stringer, eyes staring, bayonet bloody:

‘Mister Steel, Sir. They’ve come round the flank Sir, up the next street. You must come, Sir.’

Steel turned to Slaughter:

‘It’s Jennings, he’s in trouble. Take over. Re-form the men, Jacob. Reload if you can. I’ll be back as quickly as I can. And find Williams.’

He ran after Stringer, who had already begun to run away, and down the narrow alleyway connecting the two streets like the spokes on a wheel towards the town square.

It was deep black between the high walls and, looking towards the light at the end, after a few yards Steel saw the Sergeant turn left into the main street and out of sight. He continued in pursuit. He had slung the empty fusil over his shoulder and carried his sword low now, in readiness for whatever might meet him. His ears were still ringing from the crashing volley and his feet on the cobbles sounded curiously dim against the general cacophony. Even half deaf, though, as he rounded the corner, Steel was aware that something was missing. The street was silent and before he could check his pace, he realized that he had not run into some desperate struggle, but merely into a trap.

Stringer’s bayonet-tipped musket was pointed directly at his chest. Behind him, Jennings was leaning against the stone sill of a ground-floor window.

‘Ah, Steel. Thank you. Once again you come to my rescue. This time though, I am afraid that it is not myself that is in deadly peril, but you.’

Steel stood staring at the Major, all too aware of the needle-sharp point that hovered dangerously close to his throat. God damn it. How had he not seen this coming? Another duel had been inevitable. Honour must be satisfied. But like this?

‘Major Jennings. You can call off your terrier now. I’ll fight you fair. But this is not the time. We’re being beaten. We must act together for the sake of the army. We cannot afford to lose here. For pity’s sake, man. This can wait.’

‘But, Steel. Don’t you understand? Have you no idea at all? I am doing this for the sake of the army. I am aware that we cannot afford to lose here. Not the flour. The real reason for your mission.’

Steel’s eyes widened.

‘I know what you have, Lieutenant. I know what it was that you bought from Kretzmer and its importance to Marlborough. But you see it is of equal importance to those who sent me here. No, not Colonel Hawkins but those who have Britain’s true interests at heart.’

‘You bloody traitor.’

Jennings grimaced.

‘Now, now, Steel. Really, I expected better from you. You know I have come to have some respect for you over the past few days. You are a fighter, though you may be a ruffian at heart. And you do at least know your place. Unlike our brave commander, the Duke, who can never be anything more than a jumped-up farmer. We need to be led by natural leaders, Steel. By the men whose ancestors led us at Crécy and Agincourt. With that letter in their hands they will be able to bring down Marlborough and restore the army to its rightful masters. And it is my duty to ensure that they have it.’

‘You’ll have to kill me first.’

‘Oh dear. I did so hope that you weren’t going to be heroic.’

Stringer, grinning, edged the tip of his bloody bayonet closer to Steel’s throat.

‘And sincerely, Steel, I would have loved to have given you a chance in a fair fight. But now you see, as you yourself are aware, time is of the essence. Now. Your weapons, please.’

Again the bayonet moved forward. Steel dropped the sword to the ground.

‘And the gun.’