По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

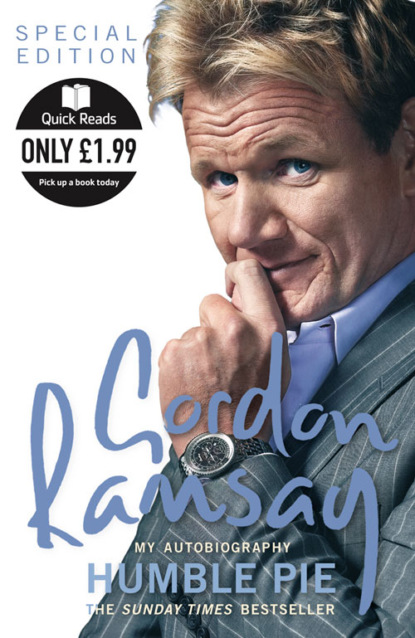

Humble Pie

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Humble Pie

Gordon Ramsay

Everyone thinks they know the real Gordon Ramsay: rude, loud, driven, stubborn. But this is his real story…In this fast-paced, bite-sized edition of his bestselling autobiography Ramsay tells the real story of how he became the world’s most famous and infamous chef: his difficult childhood, his brother’s heroin addiction, his failed first career as a footballer, his fanatical pursuit of gastronomic perfection and his TV persona - all the things that have made him the celebrated culinary talent and media powerhouse that he is today. Gordon talks frankly about:• his tough childhood: his father’s alcoholism and violence and the effects on his relationships with his mother and siblings• his first career as a footballer: how the whole family moved to Scotland when he was signed by Glasgow Rangers at the age of fifteen, and how he coped when his career was over due to injury just three years later• his brother’s heroin addiction.• Gordon’s early career: learning his trade in Paris and London; how his career developed from there: his time in Paris under Albert Roux and his seven Michelin-starred restaurants.• kitchen life: Gordon spills the beans about life behind the kitchen door, and how a restaurant kitchen is run in Anthony Bourdain-style.• and how he copes with the impact of fame on himself and his family: his television career, the rapacious tabloids, and his own drive for success.

Humble Pie

Gordon Ramsay

To Mum, from cottage pie to Humble Pie – you deserve a medal.

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#uc969b226-6e6a-5b39-8461-8523d9b6beaa)

Title Page (#u98606797-b462-5537-a3a0-f77f6fbe4bcb)

Dedication (#u677eaf7f-4f6b-56d8-acca-abf40e4c2dd2)

Foreword (#u7b53c234-b8b4-54e5-bed8-2e0b6f9c9794)

Chapter One Dad (#u9ed69999-3457-55c8-980d-9272e2eb8520)

Chapter Two Football (#u5b26b43a-394e-5f9e-a9fa-68c78ef99679)

Chapter Three Getting Started (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Four French Leave (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Five Oceans Apart (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six A Room of My Own (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven War (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight The Great Walk-Out (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine The Sweet Smell of Success (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten Welcome to the Small Screen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven New York, New York (#litres_trial_promo)

Quick Reads (#litres_trial_promo)

Other resources (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Foreword (#ulink_c2bdc7e9-b5a7-5d9d-93ed-3198338348e4)

In my hand, I’ve got a piece of paper. It’s Mum’s handwriting, and it’s a very long list of all the places we lived until I left home. It’s funny how few of them I can remember. In some cases, that’s because we were hardly there for more than five minutes. But in others, it’s because, as a boy, I was often afraid and ashamed, and always poor. And you don’t dwell on the details of a house if you connect it with being afraid, or ashamed, or poor.

I don’t think people grasp the real me when they see me on television. I’ve got the wonderful family, the big house, the flash car. I run several of the world’s best restaurants. I’m running round, cursing and swearing, telling people what to do. They probably think: that flash bastard. But my life, like most people’s, is about hard work. It’s about success. Beyond that, though, something else is at play. I’m as driven as any man you’ll ever meet. When I think about myself, I still see a little boy who is desperate to escape, and keen to please. I just keep going, moving as far away as possible from where I began. Work is who I am, who I want to be. I sometimes think that if I were to stop working, I’d stop existing.

This, then, is the story of that journey – so far. I’m just forty-one, and it seems, even to me, such an amazing and long journey in such a short time.

Will I ever get there? You tell me.

Chapter One Dad (#ulink_d2ccd247-52ad-58fb-a13d-9638c677b0dd)

The first thing I can remember? The Barras in Glasgow. It’s a market – the roughest, most weird place, full of second-hand shit. In a sense, I had a Barras kind of a childhood.

Until I was six months old, we lived in Bridge of Weir, a comfortable, leafy place just outside Glasgow. Dad, who’d swum for Scotland at the age of fifteen, was a swimming baths manager there. After that, we moved to his home town, Port Glasgow, where he was to manage another pool. Everything would have been fine had he been able to keep his mouth shut, but Dad was a hard-drinking womanizer and competitive, as much with his children as with anyone else. And he was gobby, very gobby.

Mum is softer, more innocent, though tough underneath. She’s had to be. I was named after my father, but I look more like her – the fair hair, the squashy face. I have her strength, too – the ability to keep going, no matter what life throws at me.

Mum can’t remember her mother at all – my grandmother died when she was just twenty-six, and Mum wound up in a children’s home.

At sixteen, she began training as a nurse. One Monday night, she got a pass so that she could go dancing with a girlfriend of hers. A man asked Mum to dance, and that was my father. He played in the band, and she thought he was a superstar.

When she turned seventeen, they married – on 31 January 1964 in Glasgow Registry Office. There were no guests, no white dress for her, and nothing doing afterwards, not even a drink. His father was a church elder. Kissing and cuddling were strictly forbidden. About two weeks after she was married, Mum’s mother-in-law asked Mum if she was expecting a baby.

‘No, I’m not,’ said Mum, a bit put out.

‘Then why did you go and get married?’ asked her mother-in-law.

I’ve often asked Mum this question myself. I’m glad I’m here, of course, but my father was such a bastard that it’s hard not to wonder why she stayed with him. Her answer is always the same.

‘He wanted to get married, and I thought, “Oh, it would be nice to have my own home and my own children”.’

Ten months later, my sister Diane came along and Dad got the job at a children’s home in Bridge of Weir. According to Mum, it was lovely. Then it started – the drinking and the temper. He would slap her about.

Next was the job in Port Glasgow, but Dad was all over the place. ‘Fed up,’ he used to call it. And the womanizing got steadily worse. By now, Mum was pregnant with my brother, Ronnie. One morning, Dad came home and said that his car had been stolen. It was complete bollocks. What had actually happened was that he’d been with a woman, had a few drinks, and knocked down an old man in what amounted to a hit-and-run. We had to leave, literally, overnight.

My older sister, Diane, was toddling, I was in a pushchair, and Mum was pregnant. But did he care? No. It was straight on the train to Birmingham, and who knows why. It could just as easily have been Newcastle or Liverpool.

We found a room in a shared house. Amazingly, Dad only got probation and a fine for the hit-and-run, and he soon picked up a job as a welder and joined an Irish band. All the usual kinds of women were soon hanging on to his every word, and if he went out on a Friday night, you were lucky if you saw him again before Sunday.

Needless to say, the welding soon went by the way. He was convinced that he was going to be a rock and roll star. We’d go from market to market looking for music equipment, looking at these Fender Stratocaster guitars – the fucking dog’s bollocks of the music world – and all our clothes were from jumble sales. How did he fund his shopping habit? He went to loan sharks, mostly. Because our names are the same, I’ll sometimes get investigated by companies trying to get back the cash he owes them.

On birthdays, I used to get a £3.99 Airfix model kit from somewhere like the Ragmarket, Birmingham’s version of the Barras. There’d be half of it missing, or the cardboard box it came in would be so wet and soggy that you wouldn’t have wiped your arse with it.

Christmas was terrible. When we were older, Mum always used to work in a nursing home, doing as much double-time as she could. Sometimes she didn’t even come home on Christmas Day. I used to dread Christmas. And then the bailiffs would show up. We’d be evicted. Dad’s van would be loaded up, and we’d be off to the nearest refuge or round to the social services, pleading homelessness.

As a teenager, I used to be ashamed of some of the places we lived – the ones that were riddled with damp, the ones that had been left like pigsties by other families. And every time he got violent, any ornament, any present we’d bought for Mum, would be smashed, simply because it belonged to her.

For our schooling, we were never in one place long enough to develop any kind of attention span. Dad was hardly the kind of man to insist on you doing your homework. Only poofs did homework. The same way only poofs went into catering. No, he was much more interested in trying to turn us into a country music version of the Osmonds. Diane, Ronnie and Yvonne, my younger sister, all sing and play musical instruments. They didn’t have any choice about that. Dad was obsessed. But I never went along with his plan. That’s not to say I wasn’t just as scared of him as they were. My tactic was to keep my head down and my nose clean. When I was asked to lug his bloody gear about the place, I just got on with the job. It’s funny, really, that people think of me as so forceful and combative, because that’s the precise opposite of how I was as a kid. I wouldn’t have said boo to a goose.

Gordon Ramsay

Everyone thinks they know the real Gordon Ramsay: rude, loud, driven, stubborn. But this is his real story…In this fast-paced, bite-sized edition of his bestselling autobiography Ramsay tells the real story of how he became the world’s most famous and infamous chef: his difficult childhood, his brother’s heroin addiction, his failed first career as a footballer, his fanatical pursuit of gastronomic perfection and his TV persona - all the things that have made him the celebrated culinary talent and media powerhouse that he is today. Gordon talks frankly about:• his tough childhood: his father’s alcoholism and violence and the effects on his relationships with his mother and siblings• his first career as a footballer: how the whole family moved to Scotland when he was signed by Glasgow Rangers at the age of fifteen, and how he coped when his career was over due to injury just three years later• his brother’s heroin addiction.• Gordon’s early career: learning his trade in Paris and London; how his career developed from there: his time in Paris under Albert Roux and his seven Michelin-starred restaurants.• kitchen life: Gordon spills the beans about life behind the kitchen door, and how a restaurant kitchen is run in Anthony Bourdain-style.• and how he copes with the impact of fame on himself and his family: his television career, the rapacious tabloids, and his own drive for success.

Humble Pie

Gordon Ramsay

To Mum, from cottage pie to Humble Pie – you deserve a medal.

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#uc969b226-6e6a-5b39-8461-8523d9b6beaa)

Title Page (#u98606797-b462-5537-a3a0-f77f6fbe4bcb)

Dedication (#u677eaf7f-4f6b-56d8-acca-abf40e4c2dd2)

Foreword (#u7b53c234-b8b4-54e5-bed8-2e0b6f9c9794)

Chapter One Dad (#u9ed69999-3457-55c8-980d-9272e2eb8520)

Chapter Two Football (#u5b26b43a-394e-5f9e-a9fa-68c78ef99679)

Chapter Three Getting Started (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Four French Leave (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Five Oceans Apart (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six A Room of My Own (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven War (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight The Great Walk-Out (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine The Sweet Smell of Success (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten Welcome to the Small Screen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven New York, New York (#litres_trial_promo)

Quick Reads (#litres_trial_promo)

Other resources (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Foreword (#ulink_c2bdc7e9-b5a7-5d9d-93ed-3198338348e4)

In my hand, I’ve got a piece of paper. It’s Mum’s handwriting, and it’s a very long list of all the places we lived until I left home. It’s funny how few of them I can remember. In some cases, that’s because we were hardly there for more than five minutes. But in others, it’s because, as a boy, I was often afraid and ashamed, and always poor. And you don’t dwell on the details of a house if you connect it with being afraid, or ashamed, or poor.

I don’t think people grasp the real me when they see me on television. I’ve got the wonderful family, the big house, the flash car. I run several of the world’s best restaurants. I’m running round, cursing and swearing, telling people what to do. They probably think: that flash bastard. But my life, like most people’s, is about hard work. It’s about success. Beyond that, though, something else is at play. I’m as driven as any man you’ll ever meet. When I think about myself, I still see a little boy who is desperate to escape, and keen to please. I just keep going, moving as far away as possible from where I began. Work is who I am, who I want to be. I sometimes think that if I were to stop working, I’d stop existing.

This, then, is the story of that journey – so far. I’m just forty-one, and it seems, even to me, such an amazing and long journey in such a short time.

Will I ever get there? You tell me.

Chapter One Dad (#ulink_d2ccd247-52ad-58fb-a13d-9638c677b0dd)

The first thing I can remember? The Barras in Glasgow. It’s a market – the roughest, most weird place, full of second-hand shit. In a sense, I had a Barras kind of a childhood.

Until I was six months old, we lived in Bridge of Weir, a comfortable, leafy place just outside Glasgow. Dad, who’d swum for Scotland at the age of fifteen, was a swimming baths manager there. After that, we moved to his home town, Port Glasgow, where he was to manage another pool. Everything would have been fine had he been able to keep his mouth shut, but Dad was a hard-drinking womanizer and competitive, as much with his children as with anyone else. And he was gobby, very gobby.

Mum is softer, more innocent, though tough underneath. She’s had to be. I was named after my father, but I look more like her – the fair hair, the squashy face. I have her strength, too – the ability to keep going, no matter what life throws at me.

Mum can’t remember her mother at all – my grandmother died when she was just twenty-six, and Mum wound up in a children’s home.

At sixteen, she began training as a nurse. One Monday night, she got a pass so that she could go dancing with a girlfriend of hers. A man asked Mum to dance, and that was my father. He played in the band, and she thought he was a superstar.

When she turned seventeen, they married – on 31 January 1964 in Glasgow Registry Office. There were no guests, no white dress for her, and nothing doing afterwards, not even a drink. His father was a church elder. Kissing and cuddling were strictly forbidden. About two weeks after she was married, Mum’s mother-in-law asked Mum if she was expecting a baby.

‘No, I’m not,’ said Mum, a bit put out.

‘Then why did you go and get married?’ asked her mother-in-law.

I’ve often asked Mum this question myself. I’m glad I’m here, of course, but my father was such a bastard that it’s hard not to wonder why she stayed with him. Her answer is always the same.

‘He wanted to get married, and I thought, “Oh, it would be nice to have my own home and my own children”.’

Ten months later, my sister Diane came along and Dad got the job at a children’s home in Bridge of Weir. According to Mum, it was lovely. Then it started – the drinking and the temper. He would slap her about.

Next was the job in Port Glasgow, but Dad was all over the place. ‘Fed up,’ he used to call it. And the womanizing got steadily worse. By now, Mum was pregnant with my brother, Ronnie. One morning, Dad came home and said that his car had been stolen. It was complete bollocks. What had actually happened was that he’d been with a woman, had a few drinks, and knocked down an old man in what amounted to a hit-and-run. We had to leave, literally, overnight.

My older sister, Diane, was toddling, I was in a pushchair, and Mum was pregnant. But did he care? No. It was straight on the train to Birmingham, and who knows why. It could just as easily have been Newcastle or Liverpool.

We found a room in a shared house. Amazingly, Dad only got probation and a fine for the hit-and-run, and he soon picked up a job as a welder and joined an Irish band. All the usual kinds of women were soon hanging on to his every word, and if he went out on a Friday night, you were lucky if you saw him again before Sunday.

Needless to say, the welding soon went by the way. He was convinced that he was going to be a rock and roll star. We’d go from market to market looking for music equipment, looking at these Fender Stratocaster guitars – the fucking dog’s bollocks of the music world – and all our clothes were from jumble sales. How did he fund his shopping habit? He went to loan sharks, mostly. Because our names are the same, I’ll sometimes get investigated by companies trying to get back the cash he owes them.

On birthdays, I used to get a £3.99 Airfix model kit from somewhere like the Ragmarket, Birmingham’s version of the Barras. There’d be half of it missing, or the cardboard box it came in would be so wet and soggy that you wouldn’t have wiped your arse with it.

Christmas was terrible. When we were older, Mum always used to work in a nursing home, doing as much double-time as she could. Sometimes she didn’t even come home on Christmas Day. I used to dread Christmas. And then the bailiffs would show up. We’d be evicted. Dad’s van would be loaded up, and we’d be off to the nearest refuge or round to the social services, pleading homelessness.

As a teenager, I used to be ashamed of some of the places we lived – the ones that were riddled with damp, the ones that had been left like pigsties by other families. And every time he got violent, any ornament, any present we’d bought for Mum, would be smashed, simply because it belonged to her.

For our schooling, we were never in one place long enough to develop any kind of attention span. Dad was hardly the kind of man to insist on you doing your homework. Only poofs did homework. The same way only poofs went into catering. No, he was much more interested in trying to turn us into a country music version of the Osmonds. Diane, Ronnie and Yvonne, my younger sister, all sing and play musical instruments. They didn’t have any choice about that. Dad was obsessed. But I never went along with his plan. That’s not to say I wasn’t just as scared of him as they were. My tactic was to keep my head down and my nose clean. When I was asked to lug his bloody gear about the place, I just got on with the job. It’s funny, really, that people think of me as so forceful and combative, because that’s the precise opposite of how I was as a kid. I wouldn’t have said boo to a goose.