По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

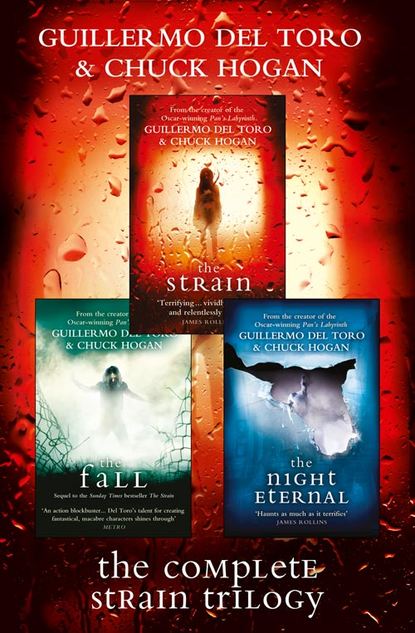

The Complete Strain Trilogy: The Strain, The Fall, The Night Eternal

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

It was throbbing.

Beating.

Eph watched the flattened, mouthlike sucker head scour the glass. He looked at Nora, next to him, staring at the heart. Then he looked at Setrakian, who hadn’t moved, hands resting inside his pockets.

Setrakian said, “It animates whenever human blood is near.”

Eph stared in pure disbelief. He edged closer again, this time to the right of the sucker’s pale, lipless receptor. The outgrowth detached from the interior surface of the glass—then suddenly thrust itself toward him again.

“Jesus!” exclaimed Eph. The beating organ floated in there like some meaty, mutant fish. “It lives on without …” There was no blood supply. He looked at the stumps of its severed veins, aorta, and vena cava.

Setrakian said, “It is neither alive nor dead. It is animate. Possessed, you might say, but in the literal sense. Look closely and you will see.”

Eph watched the throbbing, which he found to be irregular, not like a true heartbeat at all. He saw something moving around inside it. Wriggling.

“A … worm?” said Nora.

Thin and pale, lip-colored, two or three inches in length. They watched it make its rounds inside the heart, like a lone sentry dutifully patrolling a long-abandoned base.

“A blood worm,” said Setrakian. “A capillary parasite that reproduces in the infected. I suspect, though have no proof, that it is the conduit of the virus. The actual vector.”

Eph shook his head in disbelief. “What about this … this sucker?”

“The virus mimics the host’s form, though it reinvents its vital systems in order to best sustain itself. In other words, it colonizes and adapts the host for its survival. The host being, in this case, a severed organ floating in a jar, the virus has found a way to evolve its own mechanism for receiving nourishment.”

Nora said, “Nourishment?”

“The worm lives on blood. Human blood.”

“Blood?” Eph squinted at the possessed heart. “From whom?”

Setrakian pulled his left hand out of his pocket. The wrinkled tips of his fingers showed at the end of the glove. The pad of his middle finger was scarred and smooth.

“A few drops every few days is enough. It will be hungry. I’ve been away.”

He went to the bench and lifted the lid off the jar—Eph stepping back to watch—and, with the point of a little penknife from his keychain, pricked the tip of his finger over the jar. He did not flinch, the act so routine that it no longer hurt him.

His blood dripped into the serum.

The sucker fed on the red drops with lips like that of a hungry fish.

When he was done, the old man dabbed a bit of liquid bandage on his finger from a small bottle on the bench, returning the lid to the jar.

Eph watched the feeder turn red. The worm inside the organ moved more fluidly and with increased strength. “And you say you’ve kept this thing going in here for …?”

“Since the spring of 1971. I don’t take many vacations …” He smiled at his little joke, looking at his pricked finger, rubbing the dried tip. “She was a revenant, one who was infected. Who had been turned. The Ancients, who wish to remain hidden, will kill immediately after feeding, in order to prevent any spread of their virus. One got away somehow, returned home to claim its family and friends and neighbors, burrowing into their small village. This widow’s heart had not been turned four hours before I found her.”

“Four hours? How did you know?”

“I saw the mark. The mark of the strigoi.”

Eph said, “Strigoi?”

“Old World term for vampire.”

“And the mark?”

“The point of penetration. A thin breach across the front of the throat, which I am guessing you have seen by now.”

Eph and Nora were nodding. Thinking about Jim.

Setrakian added, “I should say, I am not a man who is in the habit of cutting out human hearts. This was a bit of dirty business I happened upon quite by accident. But it was absolutely necessary.”

Nora said, “And you’ve kept this thing going ever since then, feeding it like a … a pet?”

“Yes.” He looked down at the jar, almost fondly. “It serves as a daily reminder. Of what I am up against. What we are now up against.”

Eph was aghast. “In all this time … why haven’t you shown this to anyone? A medical school. The evening news?”

“Were it that easy, Doctor, the secret would have become known years ago. There are forces aligned against us. This is an ancient secret, and it reaches deep. Touches many. The truth would never be allowed to reach a mass audience, but would be suppressed, and myself with it. Why I’ve been hiding here—hiding in plain sight—all these years. Waiting.”

This kind of talk raised the hair on the back of Eph’s neck. The truth was right there, right in front of him: the human heart in a jar, housing a worm that thirsted for the old man’s blood.

“I’m not very good with secrets that imperil the future of the human race. No one else knows about this?”

“Oh, someone does. Yes. Someone powerful. The Master—he could not have traveled unaided. A human ally must have arranged for his safeguarding and transportation. You see—vampires cannot cross bodies of flowing water unless aided by a human. A human inviting them in. And now the seal—the truce—has been broken. By an alliance between strigoi and human. That is why this incursion is so shocking. And so fantastically threatening.”

Nora turned to Setrakian. “How much time do we have?”

The old man had already run the numbers. “It will take this thing less than one week to finish off all of Manhattan, and less than a month to overtake the country. In two months—the world.”

“No way,” said Eph. “Not going to happen.”

“I admire your determination,” said Setrakian. “But you still don’t quite know what it is you are up against.”

“Okay,” Eph said. “Then tell me—where do we start?”

Park Place, Tribeca

VASILIY FET pulled up in his city-marked van outside an apartment building down in Lower Manhattan. It didn’t look like much from the outside, but had an awning and a doorman, and this was Tribeca after all. He would have double-checked the address were it not for the health department van parked illegally out in front, yellow dash light twirling. Ironically, in most buildings and homes in most parts of the city, exterminators were welcomed with open arms, like police arriving at the scene of a crime. Vasiliy didn’t think that would be the case here.

His own van said BPCS-CNY on the back, standing for Bureau of Pest Control Services, City of New York. The health department inspector, Bill Furber, met him on the stairs inside. Billy had a sloping blond mustache that rode out the face waves caused by his constant jawing of nicotine-replacement gum. “Vaz,” he called him, which was short for Vasya, the familiar diminutive form of his given Russian name. Vaz, or, simply, V, as he was often called, second-generation Russian, his gruff voice all Brooklyn. He was a big man, filling most of the stairway.

Billy clapped him on the arm, thanked him for coming. “My cousin’s niece here, got bit on the mouth. I know—not my kinda building, but what can I do, they married into real estate money. Just so you know—it’s family. I told them I was bringing in the best rat man in the five boroughs.”

Vasiliy nodded with the quiet pride characteristic of exterminators. An exterminator succeeds in silence. Success means leaving behind no indication of his success, no trace that a problem ever existed, that a pest had ever been present or a single trap laid. It means that order has been preserved.

He pulled his wheeled case behind him like a computer repairman’s tool kit. The interior of the loft opened to high ceilings and wide rooms, an eighteen-hundred-square-foot condo that cost three million easily in New York real estate dollars. Seated on a short, firm, basketball-orange sofa inside a high-tech room done in glass, teak, and chrome, a young girl clutched a doll and her mother. A large bandage covered the girl’s upper lip and cheek. The mother wore her hair buzzed short; eyeglasses with narrow, rectangular frames; and a nubby, green knee-length wool skirt. She looked to Vasiliy like a visitor from a very hip, androgynous future. The girl was young, maybe five or six, and still frightened. Vasiliy would have attempted a smile, but his was the sort of face that rarely put children at ease. He had a jaw like the flat back of an ax blade and widely spaced eyes.