По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

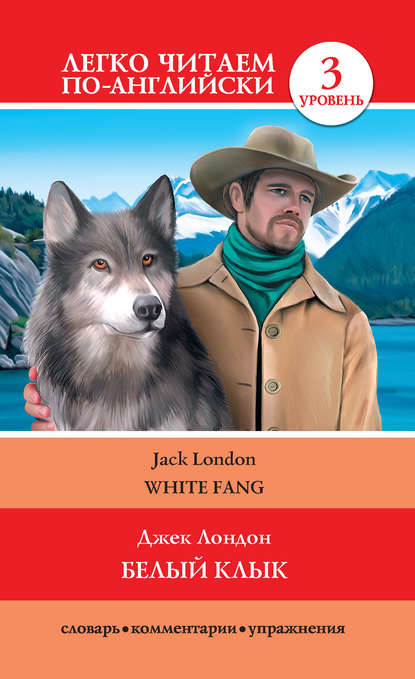

Белый клык / White Fang

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Белый клык / White Fang

Джек Лондон

Д. А. Демидова

Легко читаем по-английски

Книга содержит адаптированный и сокращенный текст классического романа Джека Лондона "Белый клык" (1906 г.). В произведении рассказывается история прирученного волка по кличке Белый Клык. Действие происходит во время золотой лихорадки на Аляске в конце XIX века.

Для удобства читателя оригинальный текст сопровождается комментариями, разными видами упражнений, а также кратким словарем.

Предназначается для продолжающих изучать английский язык (уровень 3 – Intermediate).

Джек Лондон / Jack London

Белый клык / White Fang

Адаптация текста, составление комментариев, упражнений и словаря Д. А. Демидовой

© Д. А. Демидова, адаптация текста, комментарии, упражнения, словарь

© ООО «Издательство АСТ»

Part I

Chapter I. The Trail of the Meat

Dark forest was on both sides of the waterway. The trees had been damaged by a recent wind and seemed to lean on each other. Silence ruled over the land. The land itself was lifeless, so lonely and cold that it was not even sad. There was laughter in it, but laughter more terrible than any sadness. It was the masterful wisdom of eternity laughing at the uselessness of life. It was the frozen-hearted Northland Wild.

But there was life. Down the frozen waterway ran a string of dogs. Their fur was in frost. Their breath froze in the air. Leather harness was on the dogs, and leather traces attached them to a sled which dragged behind. On the sled there was a long and narrow oblong box. There were other things – blankets, an axe, a coffee-pot and a frying-pan; but the long and narrow oblong box occupied the most space.

Before the dogs, on wide snowshoes, walked a man. Behind the sled walked a second man. On the sled, in the box, lay a third man whose walk was over, – a man whom the Wild had conquered and beaten. Life is an offence to the Wild, because life is movement; and the Wild wants to destroy movement. It freezes the water; it drives the sap out of the trees; and most terribly of all it treats man – man who is the most active of life.

But before and after the dogs walked the two men who were not yet dead. Their bodies were covered with fur and leather; eyelashes, cheeks and lips were covered with the crystals from their frozen breath; so they looked like undertakers at the funeral of some ghost. But they were men, going through the land of silence, adventurers on colossal adventure.

They travelled on without speaking to save their breath. On every side was the pressing silence. It affected their minds as the many atmospheres of deep water affect the body of the diver. It pressed all the false self-values of the human soul out of them, like juices from the grape. They felt small, having little wisdom against the great blind elements.

An hour went by, and a second hour. The light of the short sunless day was beginning to fade, when a faint far cry sounded on the air and then slowly died away. There was anger and hunger in it. The front man turned his head and his eyes met the eyes of the man behind. And then, across the narrow oblong box, they nodded to each other.

There was a second cry, somewhere behind. A third and answering cry sounded in the air.

“They’re after us, Bill,” said the man at the front.

“There’s little meat,” answered his comrade. “I haven’t seen a rabbit for days.”

They spoke no more, but listened attentively.

When it became dark they took the dogs into a cluster of trees and made a camp. The coffin served for seat and table. The dogs clustered on the far side of the fire, snarled among themselves, but didn’t go into the darkness.

“Seems to me, they’re staying remarkably close to camp,” Bill said.

His companion nodded, then took his seat on the coffin and began to eat.

“Henry, did you notice how the dogs behaved when I was feeding them?”

“They played more than usual.”

“How many dogs have we got, Henry?”

“Six.”

“Well, Henry…” Bill stopped for a moment, in order to sound more significant. “As I was saying, I took six fish out of the bag. I gave one fish to each dog, and, Henry, I was one fish short.”

“You counted wrong.”

“We’ve got six dogs. I took out six fish. One Ear didn’t get a fish. I came back to the bag afterward and got him his fish.”

“We’ve only got six dogs,” Henry said.

“Then there were seven of them that got fish.”

Henry stopped eating to count the dogs.

“There’s only six now,” he said.

“I saw the other one run off. I saw seven.”

Henry looked at him and said, “I’ll be very glad when this trip is over.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean that our load is getting on your nerves,[1 - to get on someone’s nerves – действовать на нервы] and you’re beginning to see things.[2 - you see things – тебе мерещится]”

“But I saw its tracks on the snow. I can show them to you.”

Henry didn’t reply at once. He had a final cup of coffee and wiped his mouth with the back of his hand.

“Then you think it was one of them?”

Bill nodded.

“I think you’re mistaken,” Henry said.

“Henry…” he paused. “Henry, I was thinking he was much luckier than you and me.” He pointed at the box on which they sat, “When we die, we’ll be lucky if we get enough stones over our bodies to keep the dogs off of us.”

“But we don’t have people, money and all the rest, like him. Long-distance funerals is something we can’t afford.”

“What worries me, Henry, is why a chap like this, who is a kind of lord in his own country, comes to the end of the earth.”

“Yes, he might have lived to old age if he’d stayed at home.”

Джек Лондон

Д. А. Демидова

Легко читаем по-английски

Книга содержит адаптированный и сокращенный текст классического романа Джека Лондона "Белый клык" (1906 г.). В произведении рассказывается история прирученного волка по кличке Белый Клык. Действие происходит во время золотой лихорадки на Аляске в конце XIX века.

Для удобства читателя оригинальный текст сопровождается комментариями, разными видами упражнений, а также кратким словарем.

Предназначается для продолжающих изучать английский язык (уровень 3 – Intermediate).

Джек Лондон / Jack London

Белый клык / White Fang

Адаптация текста, составление комментариев, упражнений и словаря Д. А. Демидовой

© Д. А. Демидова, адаптация текста, комментарии, упражнения, словарь

© ООО «Издательство АСТ»

Part I

Chapter I. The Trail of the Meat

Dark forest was on both sides of the waterway. The trees had been damaged by a recent wind and seemed to lean on each other. Silence ruled over the land. The land itself was lifeless, so lonely and cold that it was not even sad. There was laughter in it, but laughter more terrible than any sadness. It was the masterful wisdom of eternity laughing at the uselessness of life. It was the frozen-hearted Northland Wild.

But there was life. Down the frozen waterway ran a string of dogs. Their fur was in frost. Their breath froze in the air. Leather harness was on the dogs, and leather traces attached them to a sled which dragged behind. On the sled there was a long and narrow oblong box. There were other things – blankets, an axe, a coffee-pot and a frying-pan; but the long and narrow oblong box occupied the most space.

Before the dogs, on wide snowshoes, walked a man. Behind the sled walked a second man. On the sled, in the box, lay a third man whose walk was over, – a man whom the Wild had conquered and beaten. Life is an offence to the Wild, because life is movement; and the Wild wants to destroy movement. It freezes the water; it drives the sap out of the trees; and most terribly of all it treats man – man who is the most active of life.

But before and after the dogs walked the two men who were not yet dead. Their bodies were covered with fur and leather; eyelashes, cheeks and lips were covered with the crystals from their frozen breath; so they looked like undertakers at the funeral of some ghost. But they were men, going through the land of silence, adventurers on colossal adventure.

They travelled on without speaking to save their breath. On every side was the pressing silence. It affected their minds as the many atmospheres of deep water affect the body of the diver. It pressed all the false self-values of the human soul out of them, like juices from the grape. They felt small, having little wisdom against the great blind elements.

An hour went by, and a second hour. The light of the short sunless day was beginning to fade, when a faint far cry sounded on the air and then slowly died away. There was anger and hunger in it. The front man turned his head and his eyes met the eyes of the man behind. And then, across the narrow oblong box, they nodded to each other.

There was a second cry, somewhere behind. A third and answering cry sounded in the air.

“They’re after us, Bill,” said the man at the front.

“There’s little meat,” answered his comrade. “I haven’t seen a rabbit for days.”

They spoke no more, but listened attentively.

When it became dark they took the dogs into a cluster of trees and made a camp. The coffin served for seat and table. The dogs clustered on the far side of the fire, snarled among themselves, but didn’t go into the darkness.

“Seems to me, they’re staying remarkably close to camp,” Bill said.

His companion nodded, then took his seat on the coffin and began to eat.

“Henry, did you notice how the dogs behaved when I was feeding them?”

“They played more than usual.”

“How many dogs have we got, Henry?”

“Six.”

“Well, Henry…” Bill stopped for a moment, in order to sound more significant. “As I was saying, I took six fish out of the bag. I gave one fish to each dog, and, Henry, I was one fish short.”

“You counted wrong.”

“We’ve got six dogs. I took out six fish. One Ear didn’t get a fish. I came back to the bag afterward and got him his fish.”

“We’ve only got six dogs,” Henry said.

“Then there were seven of them that got fish.”

Henry stopped eating to count the dogs.

“There’s only six now,” he said.

“I saw the other one run off. I saw seven.”

Henry looked at him and said, “I’ll be very glad when this trip is over.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean that our load is getting on your nerves,[1 - to get on someone’s nerves – действовать на нервы] and you’re beginning to see things.[2 - you see things – тебе мерещится]”

“But I saw its tracks on the snow. I can show them to you.”

Henry didn’t reply at once. He had a final cup of coffee and wiped his mouth with the back of his hand.

“Then you think it was one of them?”

Bill nodded.

“I think you’re mistaken,” Henry said.

“Henry…” he paused. “Henry, I was thinking he was much luckier than you and me.” He pointed at the box on which they sat, “When we die, we’ll be lucky if we get enough stones over our bodies to keep the dogs off of us.”

“But we don’t have people, money and all the rest, like him. Long-distance funerals is something we can’t afford.”

“What worries me, Henry, is why a chap like this, who is a kind of lord in his own country, comes to the end of the earth.”

“Yes, he might have lived to old age if he’d stayed at home.”