По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

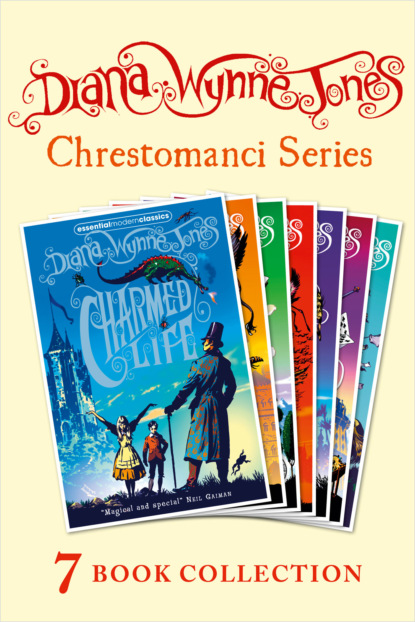

The Chrestomanci Series: Entire Collection Books 1-7

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

A minute later, Old Niccolo took his place at the head of the family and they all hurried to the gate. Paolo had just forced his way through, jostling his mother on one side and Domenico on the other, when a carriage drew up in the road, and Uncle Umberto scrambled out of it. He came up to Old Niccolo in that grim, quiet way in which everyone seemed to be moving.

“Who is kidnapped? Bernardo? Domenico?”

“Tonino,” replied Old Niccolo. “A book, with the University arms on the wrapping.”

Uncle Umberto answered, “Luigi Petrocchi is also a member of the University.”

“I bear that in mind,” said Old Niccolo.

“I shall come with you to the Casa Petrocchi,” said Uncle Umberto. He waved at the cab driver to tell him to go. The man was only too ready to. He nearly pulled his horses over on their sides, trying to turn them too quickly. The sight of the entire Casa Montana grimly streaming into the street seemed altogether too much for him.

That pleased Paolo. He looked back and forth as they swung down the Via Magica, and pride grew in him. There were such a lot of them. And they were so single-minded. The same intent look was in every face. And though children pattered and young men strode, though the ladies clattered on the cobbles in elegant shoes, though Old Niccolo’s steps were short and bustling, and Antonio, because he could not wait to come at the Petrocchis, walked with long lunging steps, the common purpose gave the whole family a common rhythm. Paolo could almost believe they were marching in step.

The concourse crowded down the Via Sant’ Angelo and swept round the corner into the Corso, with the Cathedral at their backs. People out shopping hastily gave them room. But Old Niccolo was too angry to use the pavement like a mere pedestrian. He led the family into the middle of the road and they marched there like a vengeful army, forcing cars and carriages to draw into the kerbs, with Old Niccolo stepping proudly at their head. It was hard to believe that a fat old man with a baby’s face could look so warlike.

The Corso bends slightly beyond the Archbishop’s Palace. Then it runs straight again by the shops, past the columns of the Art Gallery on one side and the gilded doors of the Arsenal on the other. They swung round that bend. There, approaching from the opposite direction, was another similar crowd, also walking in the road. The Petrocchis were on the march too.

“Extraordinary!” muttered Uncle Umberto.

“Perfect!” spat Old Niccolo.

The two families advanced on one another. There was utter silence now, except for the cloppering of feet. Every ordinary citizen, as soon as they saw the entire Casa Montana advancing on the entire Casa Petrocchi, made haste to get off the street. People knocked on the doors of perfect strangers and were let in without question. The manager of Grossi’s, the biggest shop in Caprona, threw open his plate-glass doors and sent his assistants out to fetch in everyone nearby. After which he clapped the doors shut and locked a steel grille down in front of them. From between the bars, white faces stared out at the oncoming spell-makers. And a troop of Reservists, newly called up and sloppily marching in crumpled new uniforms, were horrified to find themselves caught between the two parties. They broke and ran, as one crumpled Reservist, and sought frantic shelter in the Arsenal. The great gilt doors clanged shut on them just as Old Niccolo halted, face to face with Guido Petrocchi.

“Well?” said Old Niccolo, his baby eyes glaring.

“Well?” retorted Guido, his red beard jutting.

“Was it,” asked Old Niccolo, “Florence or Pisa that paid you to kidnap my grandson Tonino?”

Guido Petrocchi gave a bark of contemptuous laughter. “You mean,” he said, “was it Pisa or Siena who paid you to kidnap my daughter Angelica?”

“Do you imagine,” said Old Niccolo, “that saying that makes it any less obvious that you are a baby snatcher?”

“Do you,” asked Guido, “accuse me of lying?”

“Yes!” roared the Casa Montana. “Liar!”

“And the same to you!” howled the Casa Petrocchi, crowding up behind Guido, lean and ferocious, many of them red-haired. “Filthy liars!”

The fighting began while they were still shouting. There was no knowing who started it. The roars on either side were mixed with singing and muttering. Scrips fluttered in many hands. And the air was suddenly full of flying eggs. Paolo received one, a very greasy fried egg, right across the mouth, and it made him so angry that he began to shout egg-spells too, at the top of his voice. Eggs splattered down, fried eggs, poached eggs, scrambled eggs, new-laid eggs, and eggs so horribly bad that they were like bombs when they burst. Everyone slithered on the eggy cobbles. Egg streamed off the ends of people’s hair and spattered everyone’s clothes.

Then somebody varied it with a bad tomato or so. Immediately, all manner of unpleasant things were flying about the Corso: cold spaghetti and cowpats – though these may have been Rinaldo’s idea in the first place, they were very quickly coming from both sides – and cabbages; squirts of oil and showers of ice; dead rats and chicken livers.

It was no wonder that the ordinary people kept out of the way. Egg and tomato ran down the grilles over Grossi’s windows and splashed the white columns of the Art Gallery. There were loud clangs as rotten cabbages hit the brass doors of the Arsenal.

This was the first, disorganised phase of the battle, with everyone venting his fury separately. But, by the time everyone was filthy and sticky, their fury took shape a little. Both sides began on a more organised chant. It grew, and became two strong rhythmic choruses.

The result was that the objects flying about the Corso rose up into the air and began to rain down as much more harmful things. Paolo looked up to see a cloud of transparent, glittering, frozen-looking pieces tumbling out of the sky at him. He thought it was snow at first, until a piece hit his arm and cut it.

“Vicious beasts!” Lucia screamed beside him. “It’s broken glass!”

Before the main body of the glass came down, Old Niccolo’s penetrating tenor voice soared above the yells and the chanting. “Testudo!”

Antonio’s full bass backed him up: “Testudo!” and so did Uncle Lorenzo’s baritone. Feet tramped. Paolo knew this one. He bowed over, tramping regularly, and kept up the charm with them. The whole family did it. Tramp, tramp, tramp. “Testudo, testudo, testudo!” Over their bent heads, the glass splinters bounced and showered harmlessly off an invisible barrier. “Testudo.” From the middle of the bowed backs, Elizabeth’s voice rang up sweetly in yet another spell. She was joined by Aunt Anna, Aunt Maria and Corinna. It was like a soprano descant over a rhythmic tramping chorus.

Paolo knew without being told that he must keep up the shield-charm while Elizabeth worked her spell. So did everyone else. It was extraordinary, exciting, amazing, he thought. Each Montana picked up the slightest hint and acted on it as if it were orders.

He risked glancing up and saw that the descant spell was working. Every glass splinter, as it hit the unseen shield Paolo was helping to make, turned into an angry hornet and buzzed back at the Petrocchis. But the Petrocchis simply turned them into glass splinters again and hurled them back. At the same time, Paolo could tell from the rhythm of their singing that some of them were working to destroy the shield-charm. Paolo sang and tramped harder than ever.

Meanwhile, Rinaldo’s voice and his father’s were singing gently, deeply, at work on something yet again. More of the ladies joined in the hornet-song so that the Petrocchis would not guess. And all the while, the tramp, tramp of the shield-charm was kept up by everyone else. It could have been the grandest chorus in the grandest opera ever, except that it all had a different purpose. The purpose came with a perfect roar of voices. The Petrocchis threw up their arms and staggered. The cobbles beneath them heaved and the solid Corso began to give way into a pit. Their instant reply was another huge sung chord, with discords innumerable. And the Montanas suddenly found themselves inside a wall of flame.

There was total confusion. Paolo staggered for safety, with his hair singed, over cobbles that quaked and heaved under his shoes. “Voltava!” he sang frantically. “Voltava!” Behind him, the flames hissed. Clouds of steam blotted out even the tall Art Gallery as the river answered the charm and came swirling up the Corso. Water was knee-deep round Paolo, up to his waist, and still rising. There was too much water. Someone had sung out of tune, and Paolo rather thought it was him. He saw his cousin Lena almost up to her chin in water and grabbed her. Towing Lena, he staggered through the current, over the heaving road, trying to make for the Arsenal steps.

Someone must have had the sense to work a cancel-spell. Everything suddenly cleared, steam, water and smoke together. Paolo found himself on the steps of the Art Gallery, not by the Arsenal at all. Behind him, the Corso was a mass of loose cobbles, shiny with mud and littered with cowpats, tomatoes and fried eggs. There could hardly have been more mess if Caprona had been invaded by the armies of Florence, Pisa and Siena.

Paolo felt he had had enough. Lena was crying. She was too young. She should have been left with Rosa. He could see his mother picking Lucia out of the mud, and Rinaldo helping Aunt Gina up.

“Let’s go home, Paolo,” whimpered Lena.

But the battle was not really finished. Montanas and Petrocchis were up and down the Corso in little angry, muddy groups, shouting abuse at one another.

“I’ll give you broken glass!”

“You started it!”

“You lying Petrocchi swine! Kidnapper!”

“Swine yourself! Spell-bungler! Traitor!”

Aunt Gina and Rinaldo slithered over to what looked like a muddy boulder in the street and heaved at it. The vast bulk of Aunt Francesca arose, covered with mud and angrier than Paolo had ever seen her.

“You filthy Petrocchis! I demand single combat!” she screamed. Her voice scraped like a great saw-blade and filled the Corso.

(#ulink_d9762ee8-8fa0-58a6-bb3e-3aa82ae93784)

Aunt Francesca’s challenge seemed to rally both sides. A female Petrocchi voice screamed, “We agree!” and all the muddy groups hastened towards the middle of the Corso again.

Paolo reached his family to hear Old Niccolo saying, “Don’t be a fool, Francesca!” He looked more like a muddy goblin than the head of a famous family. He was almost too breathless to speak.

“They have insulted us and fought us!” said Aunt Francesca. “They deserve to be disgraced and drummed out of Caprona. And I shall do it! I’m more than a match for a Petrocchi!” She looked it, vast and muddy as she was, with her huge black dress in tatters and her grey hair half undone and streaming over one shoulder.

But the other Montanas knew Aunt Francesca was an old woman. There was a chorus of protest. Uncle Lorenzo and Rinaldo both offered to take on the Petrocchi champion in her place.

“No,” said Old Niccolo. “Rinaldo, you were wounded—”

He was interrupted by catcalls from the Petrocchis. “Cowards! We want single combat!”

Old Niccolo’s muddy face screwed up with anger. “Very well, they shall have their single combat,” he said. “Antonio, I appoint you. Step forward.”