По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

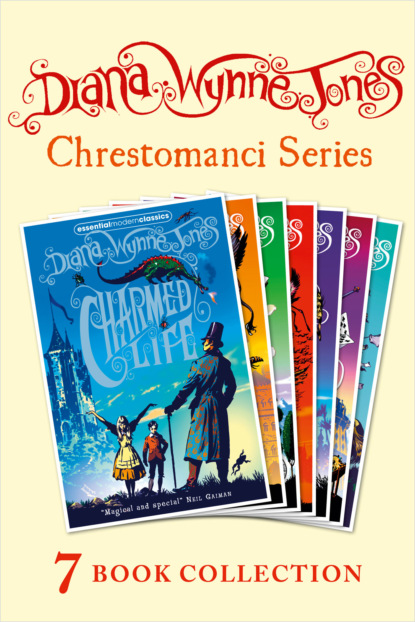

The Chrestomanci Series: Entire Collection Books 1-7

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“So are the rest of us, unfortunately,” sighed Uncle Lorenzo.

If only I could be like Giorgio, Tonino thought, as he got up from the table. I suppose what I should have to do is to find the words to the Angel. He went to school without seeing anything on the way, wondering how he could manage to do that, when the rest of his family had failed. He was realistic enough to know that he was simply not good enough at spells to make up the words in the ordinary way. It made him sigh heavily.

“Cheer up,” said Paolo, as they went into school.

“I’m all right,” Tonino said. He was surprised Paolo should think he was miserable. He was not miserable at all. He was wrapped in delightful dreams. Maybe I can do it by accident, he thought.

He sat in class composing strings of gibberish to the tune of the Angel, in hopes that some of it might be right. But that did not seem satisfactory, somehow. Then, in a lesson that was probably History – for he did not hear a word of it – it struck him, like a blinding light, what he had to do. He had to find the words, of course. The First Duke must have had them written down somewhere and lost the paper. Tonino was the boy whose mission it was to discover that lost paper. No nonsense about making up words, just straight detective work. And Tonino was positive that the book had been a clue. He must find a peeling blue house, and the paper with the words on would be somewhere near.

“Tonino,” asked the teacher, for the fourth time, “where did Marco Polo journey to?”

Tonino did not hear the question, but he realised he was being asked something. “The Angel of Caprona,” he said.

Nobody at school got much sense out of Tonino that day. He was full of the wonder of his discovery. It did not occur to him that Uncle Umberto had looked in every piece of writing in the University Library and not found the words to the Angel. Tonino knew.

After school, he avoided Paolo and his cousins. As soon as they were safely headed for the Casa Montana, Tonino set off in the opposite direction, towards the docks and quays by the New Bridge.

An hour later, Rosa said to Paolo, “What’s the matter with Benvenuto? Look at him.”

Paolo leant over the gallery rail beside her. Benvenuto, looking surprisingly small and piteous, was running backwards and forwards just inside the gate, mewing frantically. Every so often, as if he was too distracted to know what he was doing, he sat down, shot out a hind leg, and licked it madly. Then he leapt up and ran about again.

Paolo had never seen Benvenuto behave like this. He called out, “Benvenuto, what’s the matter?”

Benvenuto swung round, crouching low on the ground, and stared urgently up at him. His eyes were like two yellow beacons of distress. He gave a string of mews, so penetrating and so demanding that Paolo felt his stomach turn uneasily.

“What is it, Benvenuto?” called Rosa.

Benvenuto’s tail flapped in exasperation. He gave a great leap and vanished somewhere out of sight. Rosa and Paolo hung by their midriffs over the rail and craned after him. Benvenuto was now standing on the water butt, with his tail slashing. As soon as he knew they could see him, he stared fixedly at them again and uttered a truly appalling noise.

Wong wong wong wong-wong-wong!

Paolo and Rosa, without more ado, swung towards the stairs and clattered down them. Benvenuto’s wails had already attracted all the other cats in the Casa. They were running across the yard and dropping from roofs before Paolo and Rosa were halfway down the stairs. They were forced to step carefully to the water butt among smooth furry bodies and staring, anxious green or yellow eyes.

“Mee-ow-ow!” Benvenuto said peremptorily, when they reached him.

He was thinner and browner than Paolo had ever seen him. There was a new rent in his left ear, and his coat was in ragged spikes. He looked truly wretched. “Mee-ow-ow!” he reiterated, from a wide pink mouth.

“Something’s wrong,” Paolo said uneasily. “He’s trying to say something.” Guiltily, he wished he had kept his resolution to learn to understand Benvenuto. But when Tonino could do it so easily, it had never been worth the bother. Now here was Benvenuto with an urgent message – perhaps word from Chrestomanci – and he could not understand it. “We’d better get Tonino,” he said.

Benvenuto’s tail slashed again. “Mee-ow-ow!” he said, with tremendous force and meaning. Around Paolo and Rosa, the pink mouths of all the other cats opened too. “MEE-OW-OW!” It was deafening. Paolo stared helplessly.

It was Rosa who tumbled to their meaning. “Tonino!” she exclaimed. “They’re saying Tonino! Paolo, where’s Tonino?”

With a jolt of worry, Paolo realised he had not seen Tonino since breakfast. And as soon as he realised that, Rosa knew it too. And, such was the nature of the Casa Montana, that the alarm was given then and there. Aunt Gina shot out of the kitchen, holding a pair of kitchen tongs in one hand and a ladle in the other. Domenico and Aunt Maria came out of the Saloon, and Elizabeth appeared in the gallery outside the Music Room with the five little cousins. The door of the Scriptorium opened, filled with anxious faces.

Benvenuto gave a whisk of his tail and leapt for the gallery steps. He bounded up them, followed by the other cats; and Paolo and Rosa hurried up too, in a sort of shoal of leaping black and white bodies. Everyone converged on Antonio’s rooms. People poured out of the Scriptorium, Elizabeth raced round the gallery, and Aunt Maria and Aunt Gina clambered up the steps by the kitchen quicker than either had ever climbed in her life. The Casa filled with the sound of hollow running feet.

The whole family jammed themselves after Rosa and Paolo into the room where Tonino was usually to be found reading. There was no Tonino, only the red book lying on the windowsill. It was no longer shiny. The pages were thick at the edges and the red cover was curling upwards, as if the book was wet.

Benvenuto, with his jagged brown coat up in a ridge along his back and his tail fluffed like a fox’s brush, landed on the sill beside the book and rashly put his nose forward to sniff at it. He leapt back again, shaking his head, crouching, and growling like a dog. Smoke poured up from the book. People coughed and cats sneezed. The book curled and writhed on the sill, amid clouds of smoke, exactly as if it were on fire. But instead of turning black, it turned pale grey-blue where it smoked, and looked slimy. The room filled with a smell of rotting.

“Ugh!” said everybody.

Old Niccolo barged members of his family right and left to get near it. He stood over it and sang, in a strong tenor voice almost as good as Marco’s, three strange words. He sang them twice before he had to break off coughing. “Sing!” he croaked, with tears pouring down his face. “All of you.”

All the Montanas obediently broke into song, three long notes in unison. And again. And again. After that, quite a number of them had to cough, though the smoke was distinctly less. Old Niccolo recovered and waved his arms, like the conductor of a choir. All who could, sang once more. It took ten repetitions to halt the decay of the book. By that time, it was a shrivelled triangle, about half the size it had been. Gingerly, Antonio leant over and opened the window beyond it, to let out the last of the smoke.

“What was it?” he asked Old Niccolo. “Someone trying to suffocate us all?”

“I thought it came from Umberto,” Elizabeth faltered. “I never would have—”

Old Niccolo shook his head. “This thing never came from Umberto. And I don’t think it was meant to kill. Let’s see what kind of spell it is.” He snapped his fingers and held out a hand, rather like a surgeon performing an operation. Without needing to be told, Aunt Gina put her kitchen tongs into his hand. Carefully, gently, Old Niccolo used the tongs to open the cover of the book.

“A good pair of tongs ruined,” Aunt Gina said.

“Ssh!” said Old Niccolo. The shrivelled pages of the book had stuck into a gummy block. He snapped his fingers and held out his hand again. This time, Rinaldo put the pen he was carrying in it.

“And a good pen,” he said, with a grimace at Aunt Gina.

With the pen as well as the tongs, Old Niccolo was able to pry the pages of the book apart without touching them and peel them over, one by one. Chins rested on both Paolo’s shoulders as everyone craned to see, and there were chins on the shoulders of those with the chins. There was no sound but the sound of breathing.

On nearly every page, the printing had melted away, leaving a slimy, leathery surface quite unlike paper, with only a mark or so left in the middle. Old Niccolo looked closely at each mark and grunted. He grunted again at the first picture, which had faded like the print, but left a clearer mark. After that, though there was no print on any of the pages, the remaining mark was steadily clearer, up to the centre of the book, when it began to become more faded again, until the mark was barely visible on the back page.

Old Niccolo laid down the pen and the tongs in terrible silence. “Right through,” he said at length. People shifted and someone coughed, but nobody said anything. “I do not know,” said Old Niccolo, “the substance this object is made of, but I know a calling-charm when I see one. Tonino must have been like one hypnotised, if he had read all this.”

“He was a bit strange at breakfast,” Paolo whispered.

“I am sure he was,” said his grandfather. He looked reflectively at the shrivelled stump of the book and then round at the crowded faces of his family. “Now who,” he asked softly, “would want to set a strong calling-charm on Tonino Montana? Who would be mean enough to pick on a child? Who would—?” He turned suddenly on Benvenuto, crouched beside the book, and Benvenuto cowered right down, quivering, with his ragged ears flat against his flat head. “Where were you last night, Benvenuto?” he asked, more softly still.

No one understood the reply Benvenuto gave as he cowered, but everyone knew the answer. It was in Antonio and Elizabeth’s harrowed faces, in the set of Rinaldo’s chin, in Aunt Francesca’s narrowed eyes, narrowed almost out of existence, and in the way Aunt Maria looked at Uncle Lorenzo; but most of all, it was in the way Benvenuto threw himself down on his side, with his back to the room, the picture of a cat in despair.

Old Niccolo looked up. “Now isn’t that odd?” he said gently. “Benvenuto spent last night chasing a white she-cat – over the roofs of the Casa Petrocchi.” He paused to let that sink in. “So Benvenuto,” he said, “who knows a bad spell when he sees one, was not around to warn Tonino.”

“But why?” Elizabeth asked despairingly.

Old Niccolo went, if possible, quieter still. “I can only conclude, my dear, that the Petrocchis are being paid by Florence, Siena, or Pisa.”

There was another silence, thick and meaningful. Antonio broke it. “Well,” he said, in such a subdued, grim way that Paolo stared at him. “Well? Are we going?”

“Of course,” said Old Niccolo. “Domenico, fetch me my small black spell-book.”

Everyone left the room, so suddenly, quietly and purposefully that Paolo was left behind, not clear what was going on. He turned uncertainly to go to the door, and realised that Rosa had been left behind too. She was sitting on Tonino’s bed, with one hand to her head, white as Tonino’s sheets.

“Paolo,” she said, “tell Claudia I’ll have the baby, if she wants to go. I’ll have all the little ones.”

She looked up at Paolo as she said it, and she looked so strange that Paolo was suddenly frightened. He ran gladly out into the gallery. The family was gathering, still quiet and grim, in the yard. Paolo ran down there and gave his message. Protesting little ones were pushed up the steps to Rosa, but Paolo did not help. He found Elizabeth and Lucia and pushed close to them. Elizabeth put an arm round him and an arm round Lucia.

“Keep close to me, loves,” she said. “I’ll keep you safe.” Paolo looked across her at Lucia and saw that Lucia was not frightened at all. She was excited. She winked at him. Paolo winked back and felt better.