По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

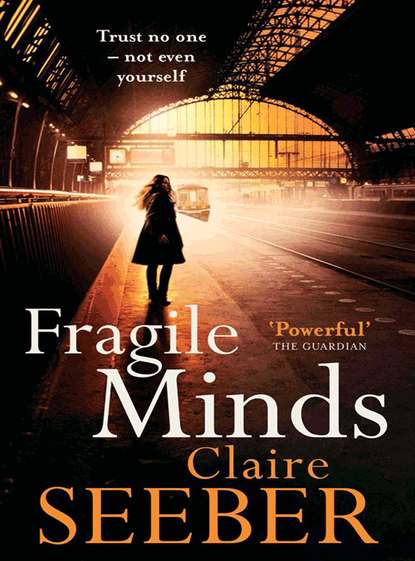

Fragile Minds

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The consultant’s single concession to my confusion and mention of blinding migraines had been to give me a blood test.

‘The confusion is probably partial concussion.’ He looked about ten, slightly nervous, hardly old enough to have left school, and his ears protruded at alarming right angles. ‘Which is what you must watch for now. Tell your family, OK? Re: the migraines, well, I haven’t got time to do a full set of bloods now,’ he filled in a form, which is what he had to find time for, ‘we’re too stretched. But let me just do a test for your hormone levels. It could explain a lot. We’ll have to wait for the results of course.’

And I hadn’t been in a hospital since that terrible day two years ago, the day that Ned had finally given up on life; and it was even worse than I remembered. There was an air of flattened panic throughout the building and everyone who entered through the sliding doors seemed almost shifty; they would check the room quickly to see who else was here as if they were casing the joint: the walking wounded, the traumatised. A constant stream of ambulances arrived in the bay outside the doors; the seriously injured were whisked somewhere we were not allowed. After a while we all averted our eyes because it was simply too much.

And the sirens; the sirens were a constant chorus of the morning, screaming through the stultifying air. The doctors and nurses walked with a different tread, faster, and they seemed different to how they would be in a normal Emergency Room; quicker, more energised. Frightened.

About an hour after I had been led to that shiny orange chair, my younger sister trotted through the doors at a fair pace, like a circus pony, anxious to perform.

‘Oh, thank God!’ she said. She was almost breathless with fear and excitement, her fair hair tumbling around her broad, friendly face, only missing its circus plume. ‘Are you OK? Isn’t this awful?’

‘Thanks for coming, Nat.’ Gingerly I stood, clutching my medication and my bag. ‘I know you’re busy.’

‘Of course I’d come.’ Her face was flushed and she had put her pink lipstick on crooked. ‘Who else would? Though I didn’t want to bring Ella into the zone, you know, the danger zone,’ and I almost laughed. ‘I left her with Glynnis next door. Such a nice woman. She understood.’

What exactly Glynnis had understood, I wasn’t sure.

‘We’d better get out of here quickly.’

‘It’s not Afghanistan you know,’ I said, but perhaps it was; perhaps this crisis that I did not understand yet was the start of something truly terrible. Natalie rolled her eyes, guiding me towards the car park now.

‘Well, who knows what it is yet, Claudia? They haven’t said. They’re saying nothing on the radio, just that it was an explosion, and don’t go into town. The traffic’s appalling. Oh God I was so worried, it’s right beside your work isn’t it? Thank goodness it happened so early.’

‘I should have been there,’ I said. I should have been there, I should have been there. ‘I was on my way in.’

‘You should? Oh my goodness, Claudia!’ she exhaled noisily. ‘You must be in shock. I would be. Your poor face. I’ve got a thermos of tea in the car.’ My ever-efficient little sister, the prizewinning Girl Guide, the soloist chorister, the parent rep. ‘You know, I can’t stop watching the news. It’s so horrific. We need to ring Mum. Let’s get home.’

FRIDAY 14TH JULY SILVER

Despite it being his day off, Joseph Silver woke at 5.15 a.m. Despite or because of … Habit was a forceful thing, he thought sourly, burying his head beneath the pillow. Silver loathed his days off, hated having time to think; he would happily spend the whole time unconscious until it was time to go to work again.

Naturally this morning, try as he might, sleep eluded him until eventually he emerged from the Egyptian cotton he’d replaced his landlady’s cheap polyester with, and lay on his back in the bed that was too soft, that sent him precariously close to one edge each time he rolled over. His upper arm was bruised from smashing into the squash court wall last night, so it was hard to get comfortable. Hands beneath his head, he stared at the ceiling, at the damp patch near the small window. And then at the framed photo beside him. He knew the picture intimately, the Dales rolling gently behind the figures in the foreground, the wide open space of his own childhood calling him, his children’s carefree faces beaming out at him, gap-toothed grins, dimples, freckles like join-the-dots. A photo pored over too many times now until it almost meant nothing. He knew it almost as well as his own face, but that brought little relief from the homesickness he so often suffered.

Silver rolled away from the three grins. Missing the children was a constant weight, like knees on his chest; a pain he fought every bloody day alongside the guilt, a guilt that called him northwards again but that he had not yet succumbed to. He wondered idly what Julie was doing today and then acknowledged that he didn’t really care. She had a good body (‘nice rack’, Craven would say and everybody else would tut and roll their eyes) but nothing much to say. She’d giggled a lot when they went to that dreadful wine bar last week and talked about police dramas. In particular, Lewis’s sidekick Hathaway, who was played by a Fox, who apparently was a fox: until Silver had had to grit his teeth. And later the sex was fine but not good enough to warrant that incessant gurgle that she thought was alluring but really wasn’t; that reminded him more of water going down a plug hole than anything else. Not good enough for him to call her on his day off – and anyway he thought he remembered her saying she was away, on some middle management course this week, which no doubt meant trust exercises of the sort that involved falling backwards and catching one another before getting pissed in the identikit hotel bar and waking up hungover and horrified next morning beside a married colleague.

Silver allowed himself a wry smile and briefly debated going to the gym, but for some reason the soulless space in the station basement held little appeal today. He swung his legs out of the bed, his bare feet meeting the polished floorboards, rubbing his short hair impatiently with both hands until it stood on end. He felt confined and caged and suddenly incredibly depressed.

Philippa’s tribe were all still in bed, which was a rare piece of luck. In an effort to cheer himself, Silver spent the next hour drinking coffee in his landlady’s huge kitchen, the early morning sunlight spilling through the old sash windows, and booking a holiday in Corfu for the kids’ October half term. Lana had actually agreed to it last time they spoke, albeit reluctantly, and he wouldn’t take the risk of asking again; he knew it was now or never. Eventually a ping from his email said he’d succeeded: three grand poorer maybe but still, the proud owner of one package holiday with perks.

Philippa plodded into the kitchen now, yawning, rubbing sleep from her almond-shaped eyes, and switched the kettle on. He raised a hand in greeting as he dialled home: the kids would be about to leave for school. He missed the boys, they’d left already, but Molly was breathless with excitement, despite Lana’s low tones chiding her to put her shoes on whilst she talked.

‘Come on, Molly.’

He heard the dull exasperation in his ex-wife’s tone and his fist clenched unconsciously, wondering why the hell she couldn’t just let him have this time, why she couldn’t relax for one moment. But he still managed to absorb the pleasure in his youngest child’s voice, words tumbling over each other about the plane, about beaches and ice cream and staying up late. Halfway through the excited patter, as Philippa padded out to the hall to start screeching at her kids who were not getting up, his mobile rang.

Kenton’s name flashed up.

‘Hang on, kiddo,’ he said to Molly and answered the mobile. ‘Silver.’

‘Sir,’ she was stammering; he could hardly hear her words for the jarring dissonance of sound behind her. ‘There’s been an incident. An explosion.’

He spoke to Molly quickly. ‘Mol. I’ll call you tonight.’

‘OK.’ For once he’d fed her enough for her to be happy to hang up. ‘Thanks, Daddy. Love you.’

‘Where are you, Lorraine?’ He stood now.

‘Berkeley Square. I was on my way to the TV place.’

He could hear pure terror in her voice; sensed her trying to suppress panic.

‘Are you OK?’

‘Yes. But – I don’t know what to—’ She was fighting tears. He could hear car alarms jostling for air space. ‘What to do.’

‘Call Control.’ Silver tucked the phone beneath his ear and reached for the remote, snapping the television on. Nothing yet. ‘I will too. And don’t do anything stupid.’

He rang Control; they knew already. He hung up. His phone rang again. It was Malloy.

‘You’d better get down here, Joe. It’s a fucking disaster.’

An appalled Philippa stood behind him as they watched the images begin to unfurl on the television. The tickertape scrolling on the bottom of the screen ‘Breaking News’; the nervous presenter, the ruined bank, the burnt bus, the smart London square now home only to distress and panic. Silver felt that familiar twist in the belly, the lurch of adrenaline that marked crisis.

‘Oh dear Lord,’ Philippa whispered. ‘Not again.’

Eyes glued to the screen, mobile clamped to his ear, Silver watched for a moment. The buzz, the rush; what he lived for. Julie and the stinking gym and the irritation Lana caused him faded entirely. He spoke to his boss.

‘I’m on my way.’

FRIDAY 14TH JULY CLAUDIE

At Natalie’s neat little house in the suburbs, Ella at least was happy to see me, demonstrating her hopping on one leg, her fair curls bouncing up and down, chunky and solid as her mother but far more cuddly.

‘Good hopping,’ I admired her. ‘Can you do the other side?’ But she couldn’t really, despite gallant efforts.

‘Please, Auntie C, can we play Banopoly?’

‘Banopoly?’ She meant Monopoly. ‘Of course. I’d love to.’

‘You can be the boot if you like,’ she said kindly, swinging on my hand. I agreed readily, because I felt like an old boot right now, and it suited me just fine to not think about real life for a moment.

‘Claudia’s hurt, Ella,’ Natalie said, but her heart wasn’t in it. She was so transfixed by the television, by the rolling news bulletins, that she wasn’t concentrating on either of us, so Ella and I sat in the kitchen, away from the television, and had orange squash and digestives as we set the Monopoly board up. In the end, I was the top hat and Ella was the dog, and I let her buy everything, especially the ‘water one with the tap on’ because I knew if she lost, her bottom lip would push out and she would cry. And I found if I didn’t move too suddenly or dramatically, the pain in my head was just about bearable.

At twelve o’clock Natalie washed Ella’s hands and face and took her round to her school nursery for the afternoon session.

‘Will you be here when I get back, Auntie C?’ Ella asked solemnly. ‘We can watch Peter Pancake if you are.’ And I smiled as best I could and said probably. She had once informed me that my complicated name was actually a man’s, and she had long since stopped struggling with it.

‘Of course you’ll be here,’ Natalie snapped, ‘where else are you going to go?’ and we looked at each other in a way that meant we were both acknowledging the reason why I wouldn’t be anywhere else.