По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

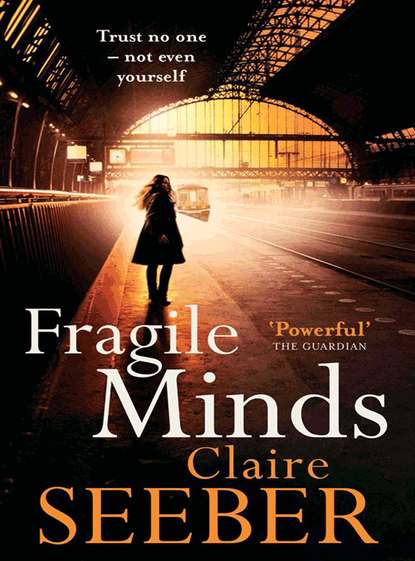

Fragile Minds

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

There was a long silence. He rolled his eyes; he thought he heard a sniff. Lana never cried.

‘What is it, kiddo?’ he tried kindness. He had ignored so many things recently, he was stamping all over his ‘emotional intelligence’ apparently; the intelligence they’d been lectured on recently at conference.

‘Don’t call me that, Joe,’ Lana snapped. ‘It drives me bloody mad.’

Some things never changed. And he didn’t have time for emotional intelligence anyway. He relied on gut instinct.

‘Sorry.’ He almost grinned. ‘What is it, Allana?’

‘I saw her on the News.’

The hairs on his arms stood up. Not this again.

‘I couldn’t sleep so I got up. It was GMTV,’ she was breathless and angry. ‘She was just there, smiling. A photo. I saw her, Joe.’

He’d thought they were through this. ‘Don’t be daft, Lana.’ Through, and out the other side. He dropped his voice to little more than a whisper. ‘We’ve been over this a million times.’ Persuasive, comforting. ‘It’s not her. It can’t be.’

‘On the News. I was watching about the bomb.’

‘Explosion,’ again, he corrected automatically.

‘Explosion. Whatever.’ Her distress was palpable. ‘They had a separate item about missing kids. She’s a dancer. I saw her face.’

‘Whose face?’ He knew who; but he needed her to say it, needed to hear the name.

A gulp, as if she were swallowing air. ‘Jaime. Jaime Malvern.’

‘Lana. Are you drunk?’

‘Nooo,’ the vowel was a long hiss, drawn-out. ‘I am stone cold sober, Joseph. But it’s her. As sure as eggs is eggs.’

They used to laugh at that expression. They used to lie in bed, legs intertwined, and do all the egg expressions: ‘Eggs in one basket, don’t count your chicken eggs.’ They were young, they were in love. They thought they were hilarious. ‘Teach your grandmother to suck eggs.’

Neither of them was laughing now.

‘Lana. It can’t be Jaime, you know that. She’s dead, kid— sweetheart. She’s been dead a long time now.’

‘I know,’ she howled, and the pain in her voice pierced him in the old way. ‘I know she’s bloody dead, Joe.’

Of course she did. Of course Lana knew this better than anyone.

‘But I saw her, Joe. I’m not mad, and I’m not drunk. Not yet anyway. I saw her.’

He stood now. ‘Lana. Don’t. You’ve done so well.’

But she’d gone. He was talking to the air.

Silver didn’t believe his ex-wife’s claims that she’d seen Jaime; he’d heard it a million times before. Allana had been haunted by Jaime’s face every day for six years, obsessed since the accident – since the afternoon that changed their lives forever. The afternoon that ruined Lana irrevocably and finished Jaime’s forever.

Silver had tried his damnedest to bring his wife back to the present, tried and failed; he’d grown used to Allana’s distress and his own guilt. He’d attempted every tactic: therapy, rehab and finally anger, until eventually he knew she was beyond reach. He mourned his lost love – for too long; until finally the mourning turned to indifference as he accepted he could no longer connect. No one could really pierce that layer of pain; not even her own children.

Silver hung up the phone feeling weary of battle. Tired and flat, he was ready for his bed – but something nagged at him. Draining the final backwash of diet Coke and crunching the can in one hand, he sat at the computer and quickly scrolled through the gallery of faces that flashed up. First the missing from the explosion: a photo album of mostly smiling anonymity, gathered quickly by frenetic journalists, posing for graduation, wedding, family snaps. Mothers, sons, nieces, nephews. Many of the families still waiting for their worst fears to be confirmed. The mess that is identifying devastated bodies after fatal accidents. Fourteen dead; the death toll still rising.

He called up the general Missing folder. Nothing. Allana was mad as ever. Not mad, he corrected himself; obsessed. Yawning until his jaw ached, Silver reached the final screen – and then – on a separate page, that face.

With a violent stab of recognition, he clicked back; pulled her up to full-screen. Slightly blurred: pretty little heart-shape, vulnerable baby face – and yet oddly tough too. Long blonde curls, widely spaced light eyes, blue maybe, too knowing for their years. Leaning into another darker girl whose face had been cropped off.

Christ.

Lana was right. He felt a finger of cold horror hook the back of his collar. She looked just like Jaime Malvern. But she couldn’t possibly be. Jaime was long dead. Who then was this girl? A doppelganger?

A ghost …

TUESDAY 18TH JULY CLAUDIE

Someone woke me, banging at the door, banging and banging until I let them in. I was so groggy I could hardly see; looking at the face on my doorstep out of one sticky eye.

Francis.

‘You didn’t come last night,’ he said, ‘and then I heard about Tessa, poor angel. Mason called.’

Bloody Mason. I bet she couldn’t wait to spread the news.

‘So I came to you. I brought chai.’

He walked past me into the flat, his thermos of tea wafting fragrant scent into my living room. But I was a little perturbed. He’d never been here. Why was he here? Had I arranged it, and forgotten this too?

On Monday, after Eduardo’s call, I had gone back to bed and hidden. I couldn’t move, couldn’t function. I lay on the bed, on top of the duvet, entirely still, until I slept again. I dreamt of Tessa. I dreamt of Ned. I feared I was going down again. I had this overriding feeling I should have saved Tessa. I couldn’t save my son – but I could have saved my friend. What had she been so scared of? I kept thinking of the lost hours before Rafe’s; the thoughts went round and round until I felt like screaming.

‘It’s not good to break the treatments,’ Francis said now, perusing the room. ‘Let me pour you tea, and then lie on the sofa and relax. I brought my needles.’

Francis was the acupuncturist and hypnotist Tessa had introduced me to when I fell off the smoking wagon; when I couldn’t sleep after Will left, when the migraines got so bad. I was a mess. I’d been a mess since Ned. ‘He’s amazing, Claudie, really; he has the hands of a genius,’ Tessa said, and so I gave it a go. Actually, I suspected Tessa was slightly in love with him, although she’d never confessed as much. She’d met him on a yoga retreat in the Cotswolds last year, I thought, and extolled his virtues ever since; in the way people who are falling in love want to use the name of their newly beloved all the time, so did she, only I feared her love was not reciprocated. Still, half the staff at the Academy were now using Francis, including a once-sceptical Mason, so Tessa’s enthusiasm had done him no harm.

Francis was certainly a unique individual; dark hair with a mullet and a deeply cared-for goatee beard, black discs in his tribally pierced ears, a shark tooth round his neck but pushing fifty, I suspected. He was friendly and empathetic, but I couldn’t for one moment see the sexual appeal Tessa obviously did, though his needles undoubtedly worked.

I drank a little of his revolting tea out of courtesy and took my jewellery off first as Francis always requested. He believed the metal interfered with my chakras and who was I to argue? I hardly knew what a chakra was. And perhaps the acupuncture would help clear my head now. I put my necklace on the sideboard and lay down on the sofa.

‘You’re not wearing a nicotine patch are you?’ he murmured as he measured my arm with his own hand, and inserted two needles near my elbow.

‘No,’ I shook my head.

‘Good girl.’ Francis chose another needle from his little box, and jabbed suddenly. A searing pain shot through my wrist.

‘Ouch!’ That had never happened before.

Francis looked troubled and took the needle out. I thought his hand was shaking a little.

‘I’m so sorry, Claudia.’ He stroked his beard. ‘My own energy is a little depleted today, I fear.’