По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

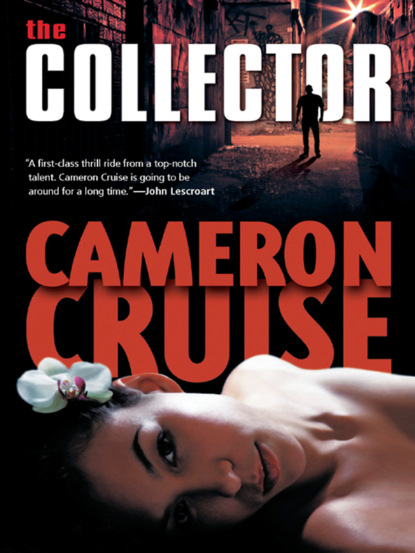

The Collector

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“I’m still trying to figure that out,” Gia said. “Maybe lots of somebodies.”

Gia didn’t bother to try to hide things from Stella. She’d learned a long time ago the futility of that—nor did Stella appreciate her efforts at protecting her. Gia chose instead to try and explain what her daughter saw. But even then, she fell short. Half the time it was Stella who told Gia the meaning behind her art, such was her daughter’s talent.

The painting didn’t show Mimi Tran’s lifeless body. Gia rarely painted death, choosing instead to objectify such things.

Mimi’s symbol was the red eye. It faced the beast, ready to do battle. But the monster proved too powerful. Part of the eye melted down the side of the canvas, the heavy red paint flowing like a river of blood off the edge.

Gia used her paintings to make sense of the images that came to her in dreams. Sometimes it worked, other times she just had macabre works of art to show for her efforts.

“They didn’t believe you, did they?”

“The police? No, darling,” she said. “They didn’t.”

She didn’t ask Stella how she knew about the police. Gia hadn’t told her about her trip to the precinct or the conversation she’d had with the detectives there. Her daughter preferred to pretend her ability was a fluke, or a figment of their imagination. She did the ostrich thing, getting angry whenever her mother pointed out the obvious.

I don’t want to be a freak like you! That’s what she’d screamed the first time her abilities came shining through.

There’d been a time when Gia, too, had said those very words to her own mother.

Stella gave a sigh that sounded much too old for her years. “I don’t know why you even try.”

“Because I was supposed to.”

“Your guides,” Stella said, in the voice of a supreme skeptic.

In the world of psychic phenomena, often times guides from the other side would help a medium make contact. They served almost as an umbilical line to the dead spirits trying to communicate. While many had names, Gia’s own guides chose to remain anonymous.

She bit her lip and stared at the simple business card propped on the easel. Detective Seven Bushard. City of Westminster. Homicide.

She remembered the electric shock of his touch.

She’d felt his sadness like a blow to her chest, making it difficult to breathe. She’d seen his story like a movie in her head. His brother and the man he’d killed. The vision had been dark and murky and without a lot of details, but grisly nonetheless.

From the moment the detective had walked in to that interview, he’d been watching her with an almost hungry stare. Gia knew what it meant to have people want something from her.

You say you had a dream?

That was the other detective. The woman, Erika Cabral. Gia recognized that tone. The freak…the nut job. It only made her smile, because she could clearly see an entity standing next to Erika, shedding a protective white light.

Gia never argued with a disbeliever. Sometimes she wondered if that’s not what she wanted. Don’t believe me. I did my duty. My conscience is clear. If you don’t make use of my knowledge, that’s not my concern.

Only, she couldn’t really say that now. Mimi Tran was different. This time, Gia wasn’t the uninvolved observer.

She might very well be responsible for that woman’s death.

She looked back at the card, remembering Seven Bushard’s words on parting.

“Call if you have another…dream,” he’d told her.

“The man. Is he going to hurt you, Mommy?”

The question came from nowhere, as they often did. Gia always forgot how connected she was to her child.

She’d been thinking about the detective when her daughter asked the question. But Stephen Bushard wasn’t who she feared.

She answered, “No, sweetie.” She kissed her daughter again, giving them both the pabulum. “I’ll be fine. We both will.”

9

The county coroner’s office was located in Santa Ana, a city that touted itself as the financial and political center for Orange County. It was over seventy-five percent Hispanic, originating with a Spanish land grant—seventy acres of which had been purchased from the Yorba family by William H. Spurgeon. Driving up the road from Westminster, Seven was always amazed how quickly the signs changed from Pho 54 to Taqueria.

Seven had grown up in nearby Huntington Beach, graduating from Marina High School. Go Vikings! With Little Saigon so close, the school’s Asian population was double that of the state average.

Even back then, there was this idea that Asian students were ruining the public school system, making it too hard for your red, white and blue American to succeed. How could Patty or Jake compete against someone who lived in the library, for God’s sake, tanking up on Top Ramen and green tea for another all-nighter of studying?

Whenever he heard someone spouting that crap, Seven always asked if maybe Asians were inherently more intelligent? No? So it’s all about good old-fashioned hard work? Well, there you go.

People made choices. They sacrificed. So quit bitching and just compete, right? God knows Ricky, his brother, hadn’t been the hit of the party scene. That had been Seven’s job in life.

Back in high school, Seven managed to get into enough hot water that his mom had threatened military school. It was a kind of periodic thing, like Easter or Christmas. Military school, Seven. I will do it! Once, she’d even taken him to tour a couple of places. Seven smiled at the memory, because the tactic had actually worked. Suddenly, he was passing all his classes.

But Ricky…it was the sweat of his brow that got him a full-ride scholarship to the college of his choice.

Still, Seven had to admit, the county coroner, Alice Wang, was the poster child for the Asians-are-hard-to-beat argument.

Alice was in her early fifties. She wore glasses and styled her hair in a sensible pageboy—Alice wasn’t spending a ton of time in front of the mirror. She had places to go, people to cut open.

Alice had a gift. Best damn medical examiner he’d ever worked with.

Mimi Tran lay on a metal table with paper draped strategically over her lower body—an attempt at dignity sabotaged by the fact that half her insides were on display and a tag hung from her big toe like a Christmas present.

Your average Joe didn’t know that it was the smells you remembered most from your first autopsy: body odors and the scent of half-digested food. Seven figured Alice and her crew must be used to it. Him, he was breathing through his mouth.

Alice Wang stood over the body of Mimi Tran. With the scalpel, she’d made a Y incision, from shoulder to shoulder and down to the lower abdomen. She’d already removed the breastplate using the circular saw waiting with other instruments next to the body, exposing the internal organs, which had all been weighed. The quickest way to know if there was something wrong was through weight.

Now she was in the process of ladling the stomach contents into a plastic container, like soup. She used tweezers to examine the particulate matter.

Apparently, Mimi Tran had had a light lunch before dying.

“Jellyfish,” Alice said, holding up a rubbery string with the tweezers.

“Not the sort of thing you keep in the fridge from the local deli?” Seven asked.

“I’m guessing not this time,” Alice said, pulling up a small, brown lump with her magic tweezers. “Escargot.”

“Jellyfish and snails?” Erika made a face. “Tell me you’re kidding.”

“This from a woman who has no doubt tickled her palate with the likes of calves’ brains and cow tongue?” Alice asked, making Seven wonder how many stomach contents from the local taqueria Alice had examined.