По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

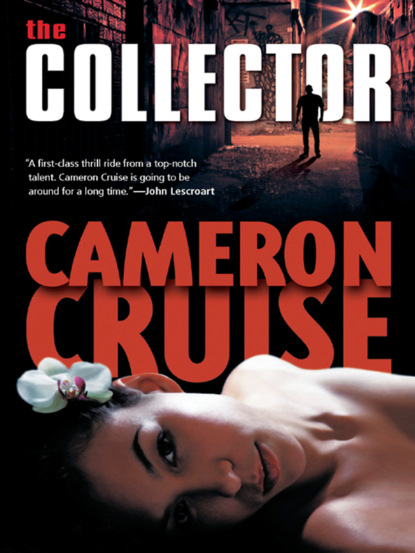

The Collector

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

You slip out of the sea and across the sand, exhilarated.

Back by the pool, a giant TV screen shows the NBA finals. Tourists take photographs of loved ones, cataloging the moment.

You don’t need a camera. You will never forget this night.

Kids slide into the pool, screaming. Spanish and English mingle in the warm, muggy night. Off in the distance, the skies now threaten a downpour, while the pool bar glows neon blue. Striped towels are handed out freely; no need for a card key tonight.

The sand poolside feels warm between your toes. You look out toward shore, where people still dance in the water. There are hammocks between a few of the palm trees, as well as striped cabana chairs. You slip into one. Again, you reach into the pocket for your souvenir. Dark clouds drifting in the night sky begin to blur the stars.

You marvel at how well it went. You were careful to slip in at the last second and take Mary’s hand in yours. No one will remember you standing with her. It was dark. That helps.

You head back to the hotel entrance. At the pool bar, an armada of bartenders flip bottles to the rhythm of a song you don’t recognize. They dance and concoct their magic potions for the women smoking and swaying to the music on the submerged concrete seats. You notice a tattoo on the small of the back of one lady, but don’t linger. You’re not greedy.

You slip inside the hotel, passing the emergency personnel scrambling by. They will try to revive Mary. They will not succeed.

They will find the tip of one of her pinkies missing where you bit it off. Not what you want for your treasure, but it will do.

Your heart is racing as you make your way to the hotel gardens. A television shows a newscaster reporting that the festival on the beaches is going well. He reassures viewers that security is tight. It’s safe, folks. Come on down and enjoy.

You enter the gardens. No one is around. Everyone is back at the pool and beach.

You listen to the frogs. They’re famous here, making a soft, coo-kee noise. It sounds like there’s hundreds just here. You open your mouth and take out the tip of Mary’s pinkie.

Now you know why they call this the island of enchantment. It’s beautiful and surreal, listening to the frogs sing.

You look down at the finger piece settled in the middle of your palm. It’s small, only to the first joint, but you did like her hands and there wasn’t a lot of time.

You’re in paradise and now you have a part of Mary. All your wishes tonight have come true….

You open your eyes, returning to time present.

Mimi Tran wasn’t nearly so nice. But she had a purpose.

The eyes, her life source, are yours now.

That’s the way it has to be from now on. You kill with reason. It’s kill or be killed. You are God and you serve a higher purpose.

And you already know who is next.

8

Gia Moon stared at the six-by-four-foot canvas. She’d come home from the police station and headed straight for her studio, dropping her purse on the concrete floor at the entrance.

She’d started work on the painting at one o’clock that morning. That’s when she’d woken from her dream.

She hadn’t woken gently, slowly easing to the surface of wakefulness. That’s not how it happened, these visions. She’d sat up abruptly, gasping for breath, horrified by the images still burning so brightly inside her head. Her daughter had uncharacteristically slept in her own bed that night, a godsend.

In her bathroom, Gia had splashed water on her face. Grabbing a robe for warmth, she’d headed for her studio in the garage.

This is what she did; it was who she was. The woman who painted nightmares.

Her mother had warned her once. You’re so strong. Be careful. Dark spirits are always attracted to the strong.

“No kidding, Mom,” she said, staring at the painting of the demon who had killed Mimi Tran.

That morning, she’d taken only a short break from painting for coffee—it wasn’t her day to drive carpool, another lucky break. She’d had more than enough time for her vision to become almost fully realized on the canvas before she’d read the article in the paper, making the connection.

Gia reached into the back pocket of her jeans and pulled out the detective’s card. When she’d gone to the precinct, she’d wanted to blurt out her story and leave. Mission accomplished.

She propped the card up on the easel.

They hadn’t believed her. She’d expected that.

She took a long breath and stared down at her hands. They were shaking. She balled her fingers into fists.

I’m next.

It had been a bold declaration, one she hadn’t planned on making. But she had a temper, and she’d let herself get pushed.

Not good, Gia.

Sometimes, she could understand what had driven her mother all those years. People wanted proof, something tangible. They wanted the world to make sense. Things needed to add up, like a mathematical formula. Forget about dreams and visions and the kooks who claimed to have them.

Erika Cabral was one of those skeptics. The kind of person who thought Gia only wanted to scam the desperate out of their money.

The interview had been surprisingly nerve-racking. Gia didn’t like the spotlight. She required anonymity. To the outside world, she was an artist, a painter whose pieces some claimed showed a glimpse into another world. But it was all below the radar. Those few souls who managed to find her never asked for more than peace of mind. In exchange for connecting with lost loved ones, they kept her secrets.

Now, that might not be possible.

“Wow. That is one ugly mother.”

Hearing her daughter, Gia turned toward the door. She had no idea how long she’d been standing there. She had a habit of “losing time” when it came to her paintings. Past three o’clock, she told herself, if Stella was home from school.

Her daughter walked into the garage studio, popping her gum, a vile habit she well knew her mother despised. Gia figured that was the point. Stella dropped her backpack in the middle of the floor. Gia didn’t comment on that, either.

The girl came to stand next to her and immediately fell into the painting.

That’s what Gia called it: falling in. It happened all the time with Stella. Gia watched as her daughter’s eyes grew unfocused. That was the problem with Stella’s gift. She was too sensitive, didn’t have strong enough defenses. She hadn’t learned how to guard herself—and, in complete denial of her gifts, she wouldn’t allow Gia to teach her.

Stella took a step back, away from the painting. In complete silence, she reached out and slipped her hand in her mom’s.

Gia pulled her little girl into her arms. At twelve years old, Stella was still under five feet, small for her age. Gia kissed the top of her head. Stella had Gia’s black hair and blue eyes. But the curls—those riotous curls brushing the tops of her shoulders were all her daughter’s.

“Okay,” Stella said, pushing back to once again look at the painting. “I already hate it. What is it?”

“I don’t know, baby. A demon of some sort.”

“It killed somebody, didn’t it?”