По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

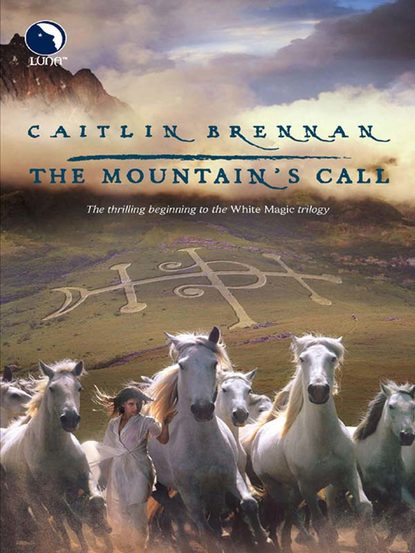

The Mountain's Call

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

He sat in the midst of them and sipped water from the bottle he had brought with him. It was still cold from the stream farther down the Mountain. He had a bit of bread in his bag, and cheese and dried apples, but he was not hungry yet.

The one he waited for arrived just after the sun touched the point of noon. He made no secret of his passage through the trees. That was deliberate, and might be construed as an insult.

Euan stayed where he was, propped on his elbow in the grass, with the water bottle in his hand. The other man rode on horseback. His mount was white, but it was not one of the gods from the school. Euan was interested to discover that he could tell the difference.

The man on the horse was small and dark and sharp-featured for a Caletanni, but he was too tall and fair to be an imperial. He looked like what he was, half-blood, with his brown hair and freckled skin. He wore his hair in a long plait, which was considered quite daring in the imperial city, but he went clean-shaven. He was not daring enough to affect the full fashion.

“Prince,” Euan greeted him.

“Prince,” he replied, swinging down off the horse with grace that few Caletanni could match. He tied up the reins and left the beast to graze, and came to stand over Euan.

“Good of you to come alone,” Euan said. “Or is there an army on the other side of the hill?”

“No army,” said the prince from Aurelia. He had a suitably imperial name, but the one he claimed in front of Euan was Gothard. “There is a company of guards not far from here. Do I need to summon them?”

“Not yet,” said Euan. He gestured expansively. “Come, sit. Be free of my hall.”

Gothard was not amused. “None of this is yours,” he said, “even after you’ve won the war. Remember the bargain. Aurelia’s throne belongs to me.”

Euan smiled his most exasperating smile. “I won’t forget,” he said.

Gothard made no secret of his doubts, but he refrained from putting them into words. He said instead, “So. You’re in the school. How goes it? Have you found a rider yet?”

“Maybe,” said Euan. “It’s only the third day since I came here. Do all your caravans march at a snail’s pace?”

“Only when time is of the essence,” Gothard said sourly. “Gods. You should have been there a month ago. Tomorrow is the Midsummer Dance. It’s a bare three months until the Great Dance.”

Euan did not comment on the pagan oath. It was a habit, one could suppose, from living with imperials. “I’m well aware of the time,” he said. His voice shifted to the half-chant of an imperial schoolboy’s recitation. “We have to be in Aurelia on the autumn equinox, when the emperor celebrates his feast of renewal, four eights of years on the throne of this empire. The white gods will leave the Mountain for that, as they have not done in a hundred years, and dance in the court of the palace. That will open the gates of time and allow us—the One God willing—to impose our will on what will be. Then the emperor will die and his heir be disposed of, and a new reign will come to Aurelia.”

“If it can be so simple and so tidy,” said Gothard, clearly annoyed by the mockery, “we’ll thank every god there is, whether he be One or many.”

“I’ll do my part,” Euan said with studied patience. “I’ll find the rider who can be persuaded—one way or another—to subvert the Dance. You have enough to do. You’ve no need to fret over that.”

“None of it is worth a clipped farthing if you fail.”

“There now,” drawled Euan. “I wouldn’t say that. If we can’t control the Dance once it’s away from the Mountain’s power, we can certainly corrupt it. We’ll have our war, one way or the other.”

“There will be war,” said Gothard, “but who will win it? The Dance can determine that—but only a rider can rule the Dance.”

“It will be done,” Euan said. “And then you will have your part to do, and so will others. In the end, we’ll win the war.”

“I envy you your surety,” Gothard said.

Euan smiled sunnily. “I’m a raving barbarian and you’re an effete imperial. Of course I’m a blind optimist. You’ll be my voice of reason, my wise philosopher.”

Truly Gothard had no humor. He was fast reaching the limits of his temper. Euan waited to see if he would say something ill-advised, but instead he froze.

Euan heard it a moment after he did. A hoof chinked softly against rock. A bit jingled even more softly.

Gothard’s grey horse had been standing still, head down and hind foot cocked, asleep. At the sound of another horse’s passing, he threw up his head.

Gothard drew a complex symbol in the air. Euan saw the shape of it limned in dark light. His skin prickled.

Two riders rode into the clearing. They were mounted on white gods. Through the veil of Gothard’s sorcery, the creatures’ coats glowed like clouds over the moon. The men were shadows encasing a core of light.

Euan sat perfectly still. Gothard’s horse stood like a marble image. Only Gothard seemed at ease. He was alert but calm. Euan had understood that Gothard was a fair journeyman of one of the innumerable schools of imperial magic, but this was a little more than journeyman’s work.

The riders never saw them. One of the horses might have cast a glance in their direction, but if it did, it did not sound the alarm. They rode on through the clearing and away.

The sun had shifted visibly when at last Gothard let go the spell. He sagged briefly and swayed, then thrust himself upright. He had to draw a deep breath before he could speak. “It’s safe,” he said. “You can move.”

Euan stretched until his bones cracked, then rotated his head on his neck. His muscles were locked tight. He released them one by one, a slow dance that Gothard watched with undisguised fascination.

Euan let his dance stretch out somewhat longer than it strictly needed. When he was as supple as he could hope to be, he was on his feet. “You’re a better sorcerer than I thought,” he said. “I salute you.” He followed the word with the action, the salute of a warrior to a champion.

Gothard accepted it with little enough grace. Euan left him there, sitting next to his motionless horse, and slipped away into the shelter of the trees.

Chapter Eleven

The last test of the Called fell three days before Midsummer. It was the only public test. Those who passed could regard it as an initiation into the life of a rider. Those who failed had the right to vanish into the crowd and be mercifully and formally forgotten.

A great number of people were gathered in the largest of the riding courts, seated in tiers above the floor of raked sand. All the riders were there, and all the candidates who had passed this test in their own day. Students from the School of War, guests and servants filled all the rest of the benches.

Some of the Called had family there. One whole flock of peacocks belonged to Paulus. Valeria saw how pale he was and felt almost sorry for him. She at least did not have to fail in front of a legion of brothers and uncles and cousins.

That gave her an unexpected pang. Her family would never see her here, or know whether she succeeded or failed. Whatever happened, she had left them. She could never go back.

All of the Called waited together in the western entrance to the court. The eights were intact except for Valeria’s, but she suspected that certain decisions had been made. Some of the Called had a drawn and haunted look. Others seemed dulled somehow, as if the magic had drained out of them.

Only a few still had a light in them. Some actually shone brighter. Iliya was one. So was Batu. And, she saw with some incredulity, Paulus.

She could not see herself, to know what the others must see. She felt strong. She had slept last night without dreams, and been awake when the bell rang at dawn. Now at full morning she was ready for whatever was to come.

Supper last night had been water from the fountain and nothing else. There had been no breakfast, but she was not hungry at all. She was dizzy and sated with the air she breathed.

She smiled at Batu who stood next to her. He smiled shakily back. “Luck,” he said.

“Luck,” she replied.

The hum and buzz of the crowd went suddenly quiet. As before, Valeria felt them before she saw them. The stallions were coming.

This time no one rode them. They were saddled and bridled, walking beside their grooms.

Her heart began to beat hard. There was not a sound in that place except the soft thud of hooves on sand, and now and then a stallion’s snort or the jingle of bit or bridle as he shook his head at a fly.

There were eight of them, as always. She had not seen these eight before. They were massive, their coats snow-white. These were old stallions, how old she was almost afraid to imagine. Their eyes were dark and unfathomably wise. The tides of time ran in them. With every step, they trod out the pattern of destiny.

She had an overwhelming desire to fling herself flat at their feet. All that kept her upright was the realization that if she did that, she would not be able to get up again. She stood with the rest of the Called, wobble-kneed but erect, and waited to be told what to do.