По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

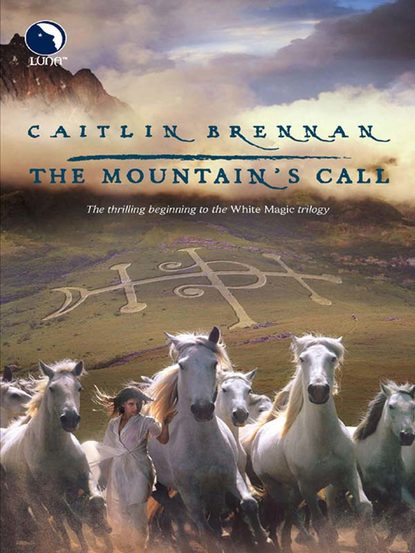

The Mountain's Call

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Valeria watched the young stallions move in their simple patterns. They were not raising great powers. They were students as she was, and only a few of them would come to the great Dance.

They were dancing a pattern that almost made sense. It had the emperor in it, and the young woman who must be the emperor’s heir, and the taller, fairer young man who looked both like and unlike them. Valeria glimpsed another face, which at first she thought was Euan Rohe’s, but this was older and harsher. It was his father’s, maybe.

The landscape of her vision was dark, lit with fire. A stone loomed against the stars, standing alone on a barren hilltop. Robed figures gathered in a circle around it. She smelled blood, strong and cloying, and the sweet stink of death.

A tattered thing flapped in the wind, wound around the top of the stone. It was a banner, a legionary standard with its device of sun and moon. Then she realized that there was something inside it. A man’s body was wrapped in the standard. His hands and feet were spiked to the stone. Blood dripped slowly, glistening in starlight.

Sunlight stabbed her skull. The Hall of the Dance was full of it. The bay Lady stood between her and the darkness.

The young stallions were still dancing, but Valeria could not stomach any more of it. Although she had been told to stand and watch, she had done as much of that as she could. She needed the sky, and the unclouded daylight.

The Lady knelt. Valeria dragged her leg over the broad back. The bay mare rose in a smooth motion and carried her out.

Valeria lay on the grass. The sky went on forever. She heard the mare grazing close by, and felt the rhythmic beat of hooves on the earth as in each court, the stallions danced.

That rhythm ruled the world. The stars sang it. It sent the moon through its phases. The sun rose and set within it.

It was as powerful as anything that was, and yet it was unspeakably fragile. In an instant it could shatter, falling into darkness and silence.

“Something wants to destroy you,” she said to Kerrec.

She did not particularly care where he was. He could hear her, she knew that.

As it happened, he was sitting on the grass beside her, almost under the bay mare’s belly. “We’ve always had enemies,” he said.

“I know. I’ve heard stories. The Red Magicians. The cult of the Nameless. Half the nobles in the court of any given reign.”

He snorted. “More than half in this reign. We’re superannuated, they declare. Our powers have eroded, if they ever actually existed. We’re a worthless collection of mountebanks on fat white ponies.”

She sat up and stared at him. “They actually say that?”

“That and worse,” he said. “I don’t suppose you were ever tested for the Augurs’ College.”

“That would be Paulus,” she said.

“Of course it would be,” said Kerrec. As usual, she could not tell what he was thinking. He masked himself too well.

She could see why he might, if he was seeing and feeling such things as she had since she came here. She was only a child, untrained and hopelessly confused. It must be overwhelming to be a master.

He stood and reached down, pulling her to her feet. The earth was unsteady under her, but his hand was strong. As soon as she could stand on her own, he let her go. “Your testing is done until tomorrow,” he said. “Apart from your duties in the stable, your time is yours to do with as you please.”

“What if I want to go back with the others?”

“You could do that,” he said. “It’s not necessary.”

“I think it might be,” she said.

He lifted a shoulder in a shrug. “As you please,” he said.

But she did not leave quite yet. “Did you find what you were looking for?” she asked.

“You know we did.”

She hardly knew what she knew, but she nodded. “Is it that overwhelming for you? Or is it worse?”

He offered no answer. She had not expected one. That, like so much else in this place, was for her to discover.

The rest of the Called were still in the schoolroom answering questions of deliberately infuriating simplicity. Valeria slipped in as quietly as she could, found a desk and a set of blank tablets, and let herself drown in words.

They were only words. She made sure of that. She had had enough magic to last her for a while.

Chapter Ten

The School of War occupied the northeastern corner of the fortress. It had its own gates and its own staff of guards and servants, even its own stables. There were no white gods there, only ordinary horses, and precious few stallions.

The hostages had been delighted to discover that once they were admitted to the school, they were no longer treated like battle captives. They were students like all the others. They shared a room in the dormitory, with as much freedom to come and go as any of the offspring of imperial nobles and rich merchants for whom this place was an entry into officers’ rank in the emperor’s armies.

“Remember,” Euan Rohe had told his kinsmen before they came here. “They want to civilize us, which means carve us into puppets. Let them teach us everything that we can learn—the better to use it against them when the Great War comes.”

They were good men, his kinsmen. Every one was a member of his own warband, sworn to him by oaths of blood and stone. The arrogant imperials had made no effort to select princes of opposing tribes, or even to discover what enmities there might be among their enemies. That, the One God willing, would be their undoing.

The lessons so far were ghastly enough. It was beneath a prince’s dignity to play the slave to a stable full of hairy, farting beasts, but if the war demanded it, then he would do it. The riding was painful but slightly less insulting. As for the handful of hours each morning in a box of a room with tablet and stylus, learning to read and write the imperial language…

“We didn’t come here for that,” Gavin said in disgust. “These scratchings on wax stain our souls.”

“They help our cause,” Euan said. “They’re not the runes that only priests can touch and live. These will gain us knowledge we might never have had otherwise. They give us power.”

“They give us corruption,” Gavin muttered, but under Euan’s glare he subsided. He submitted to instruction, and learned his letters, although he flatly refused to form them into his name. He knew better than to snare his soul.

Euan did not tell these loyal kinsmen that he already knew how to read. His father had insisted that he be taught. The old man was wise when he was sober, and he could see farther than most.

Letters, for a while, would be Euan’s secret. He pretended to struggle as the others did, and watched and waited.

He did not have to wait long. The message came through one of the grooms, a pallid young creature with a perpetually startled expression. He looked flat astonished now, but he spoke the words he had been given without a slip or a stammer.

“Tomorrow as the sun touches noon,” was Euan’s answer. “Outside the walls. Follow the trail I set.”

The boy bowed. He did not argue, as the recipient of the message almost certainly would.

He would come to the summons. He would not be able to help himself.

Euan Rohe walked openly out of the School of War, testing for once and for all the limits of his position there. No one gave him a second glance. He stood outside the high grey walls and took a long breath. It was not free air, but it was as close as he would come until this game was over.

Hunter’s instincts came back quickly in spite of more than a year in cities or under imperial guard. Euan took in the lie of the land, chose his track, and set about leaving a trail that another hunter could follow.

The place that Euan found was pleasant, a clearing in the forest that robed the Mountain’s knees. The great stands of trees were almost bare of undergrowth, but the clearing was carpeted with grass and flowers.

When he first came there, he had thought the flowers much thicker than they were. Then as he walked onto the grass, all the white blossoms took flight. They were butterflies.