По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

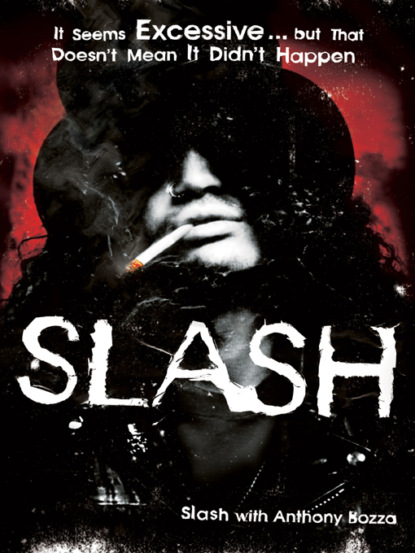

Slash: The Autobiography

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

ALL THINGS CONSIDERED, TIDUS SLOAN was pretty functional for a high school band. We played our school amphitheater and plenty of rowdy high school parties, including my own birthday. When I turned sixteen, Mark Mansfield threw a party for me at his parents’ house in the Hollywood Hills and my band was all set to play. For my birthday, my girlfriend, Melissa, gave me a gram of coke and that night I learned a valuable lesson: I do not like to combine cocaine and guitar. I did a few lines just before we went on and I could hardly play a note; it was really embarrassing. It’s been the same the very few times since that I’ve made that mistake: nothing sounded right, I could not find the groove, and I really didn’t want to be playing at all. It felt like I had never played guitar before, or as awkward as the first time I tried to ski.

We did about three songs before I just quit. I learned early to save any kind of extracurriculars for after the show. I can drink and play, but I know my limit; and as for heroin, we’ll get into that later because that’s a whole other can of worms. I did, however, learn enough to know to never carry that kind of habit on the road.

The most extravagant Tidus Sloan gig was at a bat mitzvah deep in the middle of nowhere. Adam, Ron, and I were getting high at the La Brea Tar Pits one night and met some girl who offered us five hundred bucks to play her sister’s party. When she saw that we weren’t that interested, she started dropping the names of many famous people, her “family’s friends,” who were going to be there, Mick Jagger included. We remained skeptical, but over the course of the next few hours, she built this party up to be the biggest happening in L.A. So we packed our equipment and as many friends as we could into our friend Matt’s pickup truck and set off to play this gig. The party was at the family’s house, which was about two hours from Hollywood—about an hour and forty-five minutes further than we expected; it took so long that we didn’t even know where we were by the time we got there. The moment we turned into the driveway, I found it impossible to believe that this house was about to host L.A.’s most star-studded party of the year: it was a small, old-fashioned, grandparents’ home. There were clear vinyl slipcovers on the furniture, blue shag carpet in the living room, and family portraits and china displayed on the wall. For the space available, this place was way overfurnished.

We arrived the night before and slept in their guesthouse. It was a hospitable gesture but a horrible idea, and to tell you the truth, this very proper Jewish family looked truly shocked when we arrived. We set up our equipment that night on the veranda, where they’d set out the tables and chairs and a small stage, for the next day’s performance. Then we proceeded to get completely annihilated on the load of booze we’d brought with us. We consumed it privately and did our best to contain ourselves to the guesthouse, but unfortunately, we exhausted our supply and were obliged to break into the family’s house to acquire a few bottles of whatever was readily available. Those bottles happened to be the worst ones we could have gotten our hands on: mixing our vodka, and whiskey, with Manischewitz, and a bunch of liquors that were never meant to be downed straight from the bottle spelled the beginning of a very long weekend—for us, for our hosts, and for the many guests who showed up the following morning.

Over the course of the night, our band and our friends destroyed this family’s guesthouse to a degree that surpasses nearly every similar episode that I can remember Guns ever getting into. There was puke all over the bathtub; I was sitting on the bathroom sink with this girl when it broke off the wall—water sprayed everywhere until we closed the valve. It looked as if we’d vandalized the place on purpose, but most of it was just a side effect. I am happy to say that I did not commit the worst offense of all: barfing in the stew. This dish, which was a traditional recipe served at every bar and bat mitzvah in the family, had been left to simmer overnight in the guesthouse so it would be ready to eat the next day. At some point in the evening, one of our friends lifted the lid, vomited into the pot, and replaced the lid without telling anybody—or turning off the heat. I can’t tell you quite what it was like to wake up on the floor with a raging headache, broken glass stuck to my face, and the odor of warm vomit-infused stew clinging to the air.

Unfortunately the horror show continued for this poor family. We had drunk all of our booze and all of the booze we’d stolen from the main house the night before, so we started stealing booze from the outdoor bar first thing in the morning, as we began to rehearse. Later, when the relatives filed in for the afternoon’s celebration, we were playing pretty loud and no one knew what to do or say, though a few suggestions were made.

A very peppy, very short old lady came up to offer her constructive criticism.

“Hey, you, young man, it’s too loud!” she said, squinting up at us. “Do you think you could turn it down? Some of us are trying to have a conversation!”

Grandma was slick, she had Coke-bottle black-framed glasses and a designer suit and though she was short she had complete authority. She asked us if we knew any “familiar” songs and we did our best to accommodate her. We threw in all of the Deep Purple and Black Sabbath covers that we knew. They had a stage set up for us with chairs in front of it, but it was pretty clear that aside from a few six-and eight-year-olds, the entire party was plastered against the wall farthest from the stage. Actually, the guests were behaving as if it were raining outside, because when I looked up I realized that they’d packed themselves into the living room when there was no reason to flee the open air aside from the sounds of our set.

We’d completely freaked out the partygoers, so we tried to draw them in by slowing things down: we did a heavy-metal version of “Message in a Bottle.” That didn’t work, so we tried to play whatever other popular songs we knew; we played “Start Me Up,” over and over, without a singer. It was no use; our half-hour instrumental version of it didn’t get anyone out on the floor. Out of desperation we played Morris Albert’s “Feelings,” as interpreted by Jimi Hendrix. That didn’t do it either, so we made it our swan song and got the hell out of there.

IT MIGHT BE SURPRISING TO SOME, BUT even before I had a band, I started working regularly as early as possible to earn the money that I needed to pursue playing guitar. I’d had a paper route since ninth grade that was pretty extensive; I covered from Wilshire and La Brea down to Fairfax and Beverly. It was only Sundays; I’d have to be up at six a.m. unless I could convince my grandmother to drive me. I’d have two huge bags on either end of my handle bars, so leaning just a touch too much to either side spelled wipeout. I eventually upgraded my employment to a job at the Fairfax movie theater.

The amount of time I put into work and the amount of time I put into learning the guitar were simultaneous revelations to me: I finally knew why I was putting my nose to the grindstone. I guess it was the union of my parents’ influence: my dad’s creativity and my mom’s instinct to succeed. I might choose the hardest way to get wherever I want to go but I’m always determined enough to get there. That inner drive has helped me survive those moments when everything was against me and I’ve found myself on my own with nothing else to see me through.

Work was something that I focused on and did well whether I liked my job or not, because I was willing to work my ass off all night and day for the cash to support my passion. I got a job at Business Card Clocks, a small mail-order clock factory. From September through December each year, I would assemble clocks for a bunch of companies’ holiday gift baskets. I’d put an enlarged reproduction of their business card on a piece of masonite, insert a clock movement in the center, put a wooden frame around it, box it up, and that was that. I made thousands and thousands of these things. We were paid by the hour and I was the only person there who got crazy; I’d be there at six a.m., work all day, through the night, then I’d sleep there. I don’t think it was legal, but I didn’t care: I wanted to make as much money as I could during the season.

It was a great job that I kept for quite a few years, though it did eventually bite me in the ass: my boss, Larry, paid me by personal check, so I was never on the books at his company, and he never reported my salary to the IRS. Since I wasn’t on the books, I saw no reason to pay taxes on my earnings. But the very moment that I made money with Guns a few years later, the IRS came calling, demanding all of those back taxes, plus interest. I still can’t believe that of all the things I’ve done, the government nailed me for my job at a clock factory. I found out later how it went down: the IRS audited Larry and grilled him about a certain amount of money that couldn’t be accounted for over the course of a few years so he was forced to confess that it had been paid out to his employee, me. The IRS tracked me down and put a lien on my earnings, accounts, and assets: any money that I deposited in a bank would immediately be seized to cover my tax debt. At that point, I had been broke for too long to give it all up once I’d finally gotten it: rather than pay it off with my share of Guns’ first advance check, I had my cut consolidated into traveler’s checks, which I kept on me at all times. But we’ll get to all that in just a little bit.

Another job was at the Hollywood Music Store, an instrument and sheet music shop on Fairfax and Melrose. As much as I was trying to earn my keep while pursuing what I really wanted to be doing, there were so many what-the-fuck moments. Here’s one of them: there was a guy who used to come in and shred every day in the guitar section. He’d pick a “new” guitar off the wall, as if he’d never seen it before, and proceed to play it for hours. He’d tune it, shred on it, and just kind of hang out and play for what seemed like years. I’m sure there’s one in every music store.

WHEN I STARTED JUNIOR HIGH, THERE were so many great hard rock records for me to listen to and learn from: Cheap Trick, Van Halen, Ted Nugent, AC/DC, Aerosmith, and Queen were all in their prime. Unlike a lot of my guitar-playing peers I never strove to imitate Eddie Van Halen. He was the marquee lead player around, so everyone tried to play like he did, but nobody had his feel—and they didn’t seem to realize that. His sound was so personal, I couldn’t imagine coming close, or trying or even wanting to. I picked up a few of Eddie’s blues licks from listening to him, licks that no one registers as his signature style because I don’t think he’s ever properly appreciated for his great sense of rhythm and melody. So while everyone else practised their hammer-ons and listened to “Eruption,” I just listened to Van Halen. I’ve always enjoyed individualistic guitar players, from Stevie Ray Vaughn to Jeff Beck to Jonhny Winter to Albert King, and while I’ve learned from observing their technique, absorbing the passion of their playing has taught me so much more.

In any case, things had changed by the time I got to high school. By 1980, English punk had found its way to L.A. and had become something utterly ridiculous that had nothing to do with its roots. It was a swift, impossible-to-ignore fashion statement: suddenly every older kid I knew was wearing torn-up shirts, creepers, and wallet chains made of paper clips or safety pins. I never understood what the big deal was; it was just another superficial installment in the West Hollywood scene that revolved around the Rainbow, the Whisky, Club Lingere, and the Starwood.

I never considered L.A. punk worth listening to, because I didn’t consider it real. Around then the Germs were the big band, and they had many imitators, all of whom I thought couldn’t play and totally sucked. The only bands that I thought were worth anything were X and Fear—and that was it. I respected the fact that the core of punk, from a musician’s point of view, was about not being able to play very well, and not giving a shit about it. But I had a problem with the fact that everyone in the scene exploited that aesthetic for all the wrong reasons—there’s a difference between bad playing and deliberately playing badly for a reason.

Slash doing what he does best: playing constantly.

Coming out of London and New York, punk rock made an impression, and as much as it was misinterpreted in L.A., it did give birth to a bunch of great clubs, the Café de Grand being the best of them. That was the greatest venue at which to see true hardcore punk shows, but it wasn’t the only one—the Palladium put on great hardcore shows, too. I saw the Ramones there, and I’ll never forget it—it was as intense as surfing big waves. Other than a few exceptions, L.A. punk was as pathetic as the miles of poseurs lined up outside of the Starwood every weekend.

At that time, I had finally gotten to an age where I was the older kid. I had spent my life running around being the younger guy hanging with the older kids, getting into what they were into, always wanting to be a part of the cool stuff they were doing. Now I was that kid, and as far as I was concerned, the punk movement and this really horrible fashion thing that had followed it in the back door had ruined everything. I had just gotten old enough to appreciate and enjoy all the stuff that had gone on before that, and just as I had everything started to fucking suck.

From the time I was born up until 1980, everything was pretty stable. It was all sort of based on rock and roll, despite the pretty watered-down rock bands that came out: Foghat, Styx, Journey, REO Speedwagon, and many more. From ’79 and ’80 on, with the exception of Van Halen, everything went in a different direction, which instilled a whole different kind of rebellion, and what I was into more or less got phased out by trendiness.

I wanted to play guitar in a band that inspired that degree of devotion and excitement.

AFTER I WAS EXPELLED FROM FAIRFAX High for that social studies incident I found myself in high school limbo. Education has always been a priority for my mother; she let me live wherever I could, however I wanted, all summer long, as long as I agreed to move in with her, wherever she might be, come fall. She needed real assurance that I was going to school so nothing but my living under her roof would do. The summer after my expulsion, I enrolled for summer school at Hollywood High to try to earn the credits I needed to join Beverly Hills Unified High School with the rest of the class at the beginning of my sophomore year. But I also tried to get out of high school altogether by studying for and taking the proficiency exam. It didn’t go so well: during the first half hour I took a smoke break and never went back.

During this period, my mom finally left her boyfriend, “Boyfriend” the photographer. Once Boyfriend began to freebase away, literally, everything in the house (he eventually ended up bankrupt), my mom and my brother packed up and moved out suddenly. I wasn’t spending much time at home at the time, so I didn’t witness it all go down firsthand. But when I heard, I was relieved.

My mom, brother, and grandmother moved into an apartment together on Wilshire and La Cienega and, per Mom’s rules, I joined them there in the fall. Mom wanted me to graduate high school before I set out on whatever path I chose to follow, but I hadn’t left her much to work with. My grades, attendance, and behavior record were less than stellar, so she did her best: she got me enrolled as a continuation student at Beverly Hills High.

Continuation is where they put kids with “adjustment” problems: learning disorders, behavior issues, and those who don’t otherwise sync with the standard curriculum. Whereas at Fairfax I thought this was a situation to avoid, here it was perfect for me; I was allowed to work at my own pace, and I could set my hours to suit my new place in the workforce. I’d arrive at eight and leave at noon because I had two jobs at the time; aside from the Fairfax movie theater, the fall was high season at the clock factory.

My classmates in Continuation Education at Beverly Hills High were a real cast of characters. There were a couple of full-on Harley-Davidson biker chicks, one that was a behemoth, whose heavy-set, fortysomething, Hell’s Angels boyfriend picked her up every day. He’d arrive early and just sit there revving his engine; the other chick had her own Harley. There were also three Sunset Strip rocker chicks in class; their Aqua Net hair extended in every direction and their ripped-up T-shirts and spiked stiletto heels spoke for themselves. All three were attractive in their own way …they knew how to use lipstick and eye shadow, put it that way. I knew this other girl in class: her name was Desiree, the daughter of one of my dad’s friends, Norman Seiff, a well-known rock photographer. We were playmates when we were little and we used to play naughty with each other back then. I had a crush on her all those years ago and I had so many more reasons to have a crush on her when I saw her again: she sat a row in front of me and wore nothing but loose sleeveless shirts and no bra. She had grown into a hot buxom punk rocker, who was still as cute to me as she had been when we were seven.

There was other riffraff in that class as well; we were a diverse and outlandish enough group that we could have been collectible figurines: there was the surfer-stoner Jeff Spicoli guy, the hot teenage mom-slut, the plump brooding Goth, the sad Indian kid who worked the night shift at his parents’ 7-Eleven; all of us barely clinging to the fringe of high school society. Looking back, I’d like to know how every person in the classroom ended up there, at the otherwise ritzy Beverly Hills High, no less. We were sequestered together for the benefit of our “progressive” education in one classroom with one coed bathroom that doubled as our community smoking lounge. That is where I discovered why those three Sunset Strip rocker chicks looked like they did: they were the unofficial presidents of the Mötley Crüe fan club. They did free PR as well: they turned me on to Mötley during the first smoke break I shared with them.

I had known about Nikki Sixx, the bassist and creator of Mötley Crüe, since his first band, London, because Steven and I saw them play the Starwood one night when we managed to sneak in. London had true stage presence; combined with their low-budget pyrotechnics and Kiss-esque clothes, they were band enough to blow any teenage mind. I had no idea that Nikki had met Tommy and that they had found the other guys and evolved into Mötley Crüe; neither did I know that they were spearheading a movement that would displace L.A. punk overnight. Mötley didn’t look like Quiet Riot, Y&T, or any other Sunset Strip band of the day: they were as equally over the top but they weren’t quite like anyone else. They were so into their own thing that there was no way that anyone, aside from me I suppose, could have mistaken these three girls for anything other than Mötley Crüe fans.

There are moments in life that only time can properly frame; at best you know the snapshot is special when you take it, but most of the time only distance and perspective prove you right. I had one of those moments just before I ditched education altogether: it was the day Nikki Sixx and Tommy Lee showed up outside of my school. Six years later I’d be doing lines with them off the flip-down meal trays on their private jet, but seeing them loitering outside Beverly Hills High is more memorable to me. They were wearing high-heeled boots, stretch pants, teased out hair, and makeup; they were smoking cigarettes; talking to girls in my high school parking lot. It was sort of surreal. I watched my newfound continuation friends, those three Mötley look-alike chicks, stare at the two of them with glazed doughnut eyes as Tommy and Nikki nonchalantly handed them posters to hang and flyers to hand out on the Strip announcing Mötley’s next show. I was in awe: not only did these chicks find this band so exciting that they chose to dress like them, they were also willing to be their volunteer street team. Nikki had given them copies of their new EP, Too Fast for Love, and their job was to convert all their friends into Mötley Crüe fans. It was like seeing Dracula set his disciples loose on Beverly Hills to suck the blood of virgins.

I was impressed and objectively envious: I could never be in a band that looked or sounded like Mötley Crüe, but I wanted what they had. I wanted to play guitar in a band that inspired that degree of devotion and excitement. I went to see Mötley that weekend at the Whisky …musically, it was just okay, but as a concert it was effective. It was memorable because of the full-on production: Vince lit Nikki’s thigh-high boots on fire and they set off a ton of mini flash pots. Tommy pounded away like he wanted to split his drum set in two, while Mick Mars shuffled around his side of the stage, hunched over like the walking dead. What affected me the most, though, was the audience: they were so die-hard that they sang every song and rocked out as if the band were headlining the L.A. Forum. It was obvious to me at least, that soon, Mötley would be doing just that. And in my mind, that meant only one thing: If they can do it on their own terms, why the fuck can’t I?

5

Least Likely to Succeed

Once you’ve lived a little you will find that whatever you send out into the world comes back to you one way or another. It may be today, tomorrow, or years from now, but it happens; usually when you least expect it, usually in a form that’s pretty different from the original. Those coincidental moments that change your life seem random at the time, but I don’t think they are. At least that’s how it’s worked out in my life. And I know I’m not the only one.

I hadn’t seen Marc Canter in about a year, for no other reason than that we’d each been busy doing other things. In the interim, he’d undergone a metamorphosis: when I’d seen him last, he was a music fan and was just beginning to take on a role in running the family business at Canter’s Deli. He was by no means a total “rock guy”—that was more my angle, if broad strokes were drawn. When we reconnected, Marc was someone else entirely: he was a sterling specimen of the obsessed, die-hard rock devotee. I wouldn’t have called it in a million years, but he’d dedicated his entire life to Aerosmith. He’d transformed his room into a wall-to-wall shrine: his Aerosmith posters were a continuous collage that looked like wallpaper, he had cataloged copies of every magazine that they’d ever appeared in, he maintained an orderly gallery, in plastic sleeves, of signed photographs, and he had amassed enough rare foreign vinyl and bootleg concert cassettes to open a record store.

Marc definitely didn’t dress the part; he looked like no more than a rock fan with a taste for Aerosmith T-shirts, because he never let his fandom go so far as to inspire sartorial homage to Steven or Joe. It did, however, inspire stalking, stealing, trespassing, and a few other mildly illegal pursuits in the name of the cause. Marc had also gotten himself in with the local ticket-scalping community somehow: he’d buy a load of tickets for a show, then trade among the scalpers until he had bartered his way up to the perfect pair of floor seats. It was all a big game to him; he was like a kid trading baseball cards, but come showtime, he was the kid who walked away with the rarest cards up for grabs.

Once Marc had his seats sorted out, his little operation was just getting going. He’d sneak in a very nice, professional-grade camera and a collection of lenses by taking the whole apparatus apart and stashing the individual pieces in his pants, the arms of his jacket, and wherever else they fit. He never got caught; and he just caught amazing live shots of Aerosmith. The only problem was that he got into Aerosmith a little too late: when he started really digging them they broke up.

A cornerstone of Marc’s collection of Aerosmith memorabilia was an empty bag of Doritos and a small Ziploc bag full of cigarette butts that he’d snatched from Joe Perry’s hotel room at the Sunset Marquis. Apparently he’d staked the place out and managed to get in there after Joe checked out and before housekeeping showed up. Joe hadn’t even played a show or anything the night before—at that point, he had quit the band actually. I thought it was a little weird, Aerosmith wasn’t even together, but Marc was living for them 24/7. Marc has been one of my best friends in life since the day we met, so I had to support him by contributing to his collection: I did a freehand sketch of Aerosmith onstage for his birthday. I did it in pencil and then shadowed and highlighted it with colored pens and it came out pretty good.

That picture taught me a lesson that’s been stated by the wise and otherwise throughout history: whatever you put out into the world comes back to you one way or another. In this instance, that picture came back to me literally and brought with it just what I’d been looking for.

The next time I saw the drawing I was at an impasse: I had been struggling unsuccessfully to get a band together amid a music scene that didn’t speak to me at all. I wanted the spoils that I watched lesser players enjoy, but if that meant changing as much as I’d have to, I wasn’t having that—I tried but I found that I was incapable of too much compromise. I won’t lie now that retrospect is on my side and claim that deep down I knew it would all come together fine. It didn’t look like it was going that way at all, but it didn’t keep me from doing the only thing I could do: I did what felt right, and somehow, I got lucky. I found four other dysfunctional like-minded souls.

I was working in the Hollywood Music Store the day a slinky guy dressed like Johnny Thunders came up to me. He was wearing tight black jeans, creepers, dyed black hair, and pink socks. He had a copy of my Aerosmith drawing in his hand that a mutual friend had given him: apparently prints of it had been made and circulated. This guy had been inspired enough to seek me out, especially when he heard that I was a lead guitar player.

“Hey, man, are you the guy who drew this?” he asked a bit impatiently. “I dig it. It’s fuckin’ cool.”

“Yeah, I did,” I said. “Thanks.”

“What’s your name?”

“I’m Slash.”

“Hey. I’m Izzy Stradlin.”

We didn’t talk for long; Izzy has always been the kind of guy with somewhere else that he needed to be. But we made a plan to hang out later on, and when he came by my house that night, he brought me a tape of his band. It couldn’t have sounded worse: the tape was the cheapest type around, and their rehearsal had been recorded through the built-in mike in a boom box that had been placed on the floor. It sounded like they were playing deep inside a jet engine. But through the static din, way in the background, I heard something intriguing, that I believed to be their singer’s voice. It was hard to make out and his squeal was so high-pitched that I thought it might be a technical flaw in the tape. It sounded like the squeak that a cassette makes just before the tape snaps—except it was in key.

AFTER MY INCOMPLETE STINT AT HIGH school, I lived with my mother and grandmother in a house on Melrose and La Cienega in a small basement room off the garage. It was perfect for me; if need be, I could slip out of the street-level window undetected at any time of day or night. I had my snakes and my cats down there; I could also play guitar whenever I liked without bothering anyone. As soon as I dropped out of school, I agreed to pay my mother rent.

As I mentioned, I held several day jobs while trying to put together or get into a band that I believed in amid the quagmire of the L.A. metal scene. Around this time, I worked for a while at Canter’s Deli in a job that Marc basically invented for me. I worked alone upstairs in the banquet room, which wasn’t suited for a banquet at all—it was more or less where they stored all kinds of shit that they didn’t necessarily need. I didn’t realize the humor in that back then.