По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

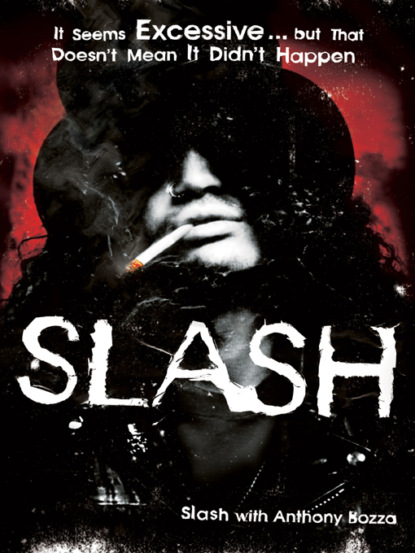

Slash: The Autobiography

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Once I got back to the apartment I was living in at the time, I realized my new “purchases” would best serve each other by becoming one: I cut the belt to fit the top hat and was happy with the way it looked. I was even happier to discover that with my new accessory pulled down as far as it could go, I could see everything but no one could really see me. Some might say that a guitarist hides behind his instrument anyway, but my hat added an impenetrable comfort. And while I never thought it was original, it was mine—a trademark that became an indelible part of my image.

WHEN GUNS FIRST GOT GOING I WAS working at a newsstand on Fairfax and Melrose. I lived with my on-again, off-again girlfriend Yvonne full-time until she got sick of me, at which point we broke up once more, leaving me nowhere to live. My former manager at the newsstand, Alison, let me crash in her living room and pay her half of the rent. She was a very handsome reggae chick with an apartment on Fairfax and Olympic who was taking college classes at night. Alison was attractive, but I always thought that either she was a little old for me or that I was a little young for her; either way, we never had that kind of relationship. We got along very well, and when she left the newsstand for a better job, I was lucky enough to inherit her position.

Alison always treated me like the cute stray she’d taken in, and I did little to prove her wrong. As her tenant, I didn’t take up much space. My worldly possessions were my guitar, a black trunk full of rock magazines, cassettes, an alarm clock, some pictures, and whatever clothes I owned or had been given by friends and girlfriends. And there was my snake, Clyde, in his cage.

Anyway, the newsstand job came to an abrupt end in the summer of ’85 when a local rock station, KNEC, threw a party out in Griffith Park, complete with free charter buses that departed from the Hyatt on the Sunset Strip. I headed over there after work with two pints of Jack Daniel’s in my jeans, not giving a shit that I was expected to open the newsstand up at five the next morning. It was a pretty debauched summer night as I recall; people passed bottles and joints as the bus made its way across town. There were plenty of local characters and musicians on board, and when we got there, music playing and a barbecue. The grass was full of people engaged in everything.

I got so fucked up that night that I brought a girl back to Alison’s place and was fucking her on the living-room floor when Alison came home and caught us. She didn’t need to say anything—her expression told me that she wasn’t too pleased. I stayed up with this girl anyway until it was time for me to go to work. By the time I got her dressed and on her way, I was already late and my boss, Jake, had called. I was in the doghouse already because I used the phone at the newsstand to conduct band business so often that he’d started calling during my shifts to catch me in the act, which proved to be difficult. Those were the days before call waiting and I was on the phone constantly so it took Jake hours to get through just to yell at me. Needless to say he was pretty pissed off about opening up for me that day.

“Yeah, Jake, I’m sorry,” I mumbled, still pretty drunk when he called for the second time. “I know I’m late, I got held up. But I’m on my way.”

“Oh, you’re on your way?” he asked.

“Yeah, Jake, I’ll be there really soon.”

“No you won’t,” he said. “Don’t bother. Not today. Not tomorrow. Not ever.”

I paused for a minute and let that sink in. “You know, Jake, that’s probably a good idea.”

AT THAT TIME DUFF AND IZZY STILL lived across the street from each other on Orange Avenue. Duff had a working-class-musician mentality like mine—until the band really got going, he didn’t feel right if he didn’t have a job, even if his job was morally suspect. He did phone sales or phone theft, depending on your point of view: Duff worked as a telemarketer for one of those firms that promise people a prize of some kind if they agree to pay a small fee “in order to redeem it.” I had a similar job before I got my job in the clock factory: I’d call people all day, promising them a Jacuzzi or a tropical vacation if they’d just “confirm” their credit-card number to cover their “eligibility fee.” It was a nasty, cutthroat gig and I got out the day before it was raided by the police.

Axl and Steven would do anything not to work a regular job, so they got by on the street, or via their girlfriends’ handouts. Though, as I recall, on occasion Axl and I took jobs together as extras on movie sets. We were in a few crowd shots at the L.A. Sports Arena for a Michael Keaton movie called Touch and Go where he played a hockey player. We didn’t care as much for the camera time as we did getting fed and making money for doing nothing: we’d show up in the morning, get our meal ticket, then find somewhere to sleep behind the bleachers where we wouldn’t be found. We’d wake up when they called for lunch to eat with the rest of the crowd, then sleep until it was time to clock out and collect our hundred-dollar check.

I liked being the industry’s least industrious extra as often as possible: I found absolutely nothing wrong with free lunch and an afternoon of being paid to sleep. I looked forward to the same when I was scouted by a casting director for the film Sid and Nancy. Unbeknownst to any of us, the same casting director in various locales, scouted every single member of Guns N’ Roses individually. All of us showed up to the first day of casting, like, “Hey …what are you doing here?”

It wasn’t much fun; actually, it was like jury duty: there was a pen full of extras, but all five of us were chosen to be in the same concert scene, where “the Sex Pistols” are playing some small club. The shoot required showing up early in the morning, for three consecutive days, with the usual promise of a meal ticket and a hundred bucks each day. A three-day commitment was too much for the other guys. In the end, I was the only one of us pathetic enough to show up for the duration.

Fuck them, I had a blast; for three days, they shot these “Sex Pistols” concert scenes at the Starwood, a club that I knew inside and out. I’d show up in the morning, clock in and get my meal ticket, then disappear into the bowels of the Starwood and get drunk on Jim Beam all by myself. While the other extras were doing their part playing audience members down on the floor in front of the stage, I watched the proceedings from a hidden corner of the mezzanine—and got paid the same wage.

AS GUNS BECAME A CLUB BAND TO BE reckoned with, a few ridiculous L.A. managers started to circle us like sharks, claiming that they had what it took to make us stars. At this point we had amicably and temporarily parted ways with Vicky Hamilton, so we were open to offers, but most of those that we got were just retarded. One of the more convincing examples of how low those types will go and what would be in store for us should we make that mistake came courtesy of Kim Fowley, the infamous character who managed the Runaways the way Phil Spector managed the Ronettes; basically just a legalized form of indentured servitude. Kim gave us his best lines, but the moment he talked about taking a percentage of our publishing and making a long-term creative commitment to him, it was clear what he had in mind. His bullshit and demeanor spoke for themselves because Kim was too odd of a guy to fake it.

I liked him nonetheless and was happy to hang out and be entertained by him—as long as he didn’t get too close. The rest of us were the same kind of animal: willing to take advantage of everything someone might have to offer without making any promises we’d have to keep. Axl would hang out as long as the conversation was worthwhile because Axl is a good talker. Steven was there if there were chicks involved. And I was willing to consume all of the free Denny’s meals, cigarettes, drinks, and drugs in exchange for the conversation I had to put up with. Once the factors that had drawn us in were exhausted, one by one, we’d make our exit.

Kim introduced us to a guy named Dave Liebert, who was Alice Cooper’s tour manager for a time and had worked with Parliament-Funkadelic, only God knows when, and those two were intent on signing us as a team, and taking us for all we were worth. Kim took me over to Dave’s house to meet him one night and I remember Dave showing us his gold records. His attitude was “Hey, kid, this could be you.” I assume he intended to entice me further by inviting two girls over, who were young enough to be his daughters, that spent the night shooting speed in the bathroom. Dave dragged me in there at one point and it seemed like these chicks had no idea what they were doing. They were so inept that I wanted to grab the needle and inject them myself. Dave was into it and, in the unbearable fluorescent light of that bathroom, stripped down to his underwear and fooled around with these girls—who were nineteen at best—and invited me to join in. I remember thinking that of all the reasons why this scene was so very scummy, the lighting was worst of all. The thought of this guy managing our band and Kim Fowley with his collection of prehistoric gold records made it nearly impossible not to just laugh hysterically right in his face. It would have been professional suicide before we ever had something to lose. We’d never stand a chance if the management was as debaucherous as the band, anyway.

AS GUNS KEPT REHEARSING, WRITING, and gigging, working to define who we were, I started going out more. Suddenly there were actually bands I wanted to see because finally the scene was changing: there were bands like Red Kross who were a glam band, but were gritty, and at the other end of the spectrum, there were bands like Jane’s Addiction who were great and that I related to but I wasn’t on the same page with. We played shows with some of those more obscure, arty bands—I remember a gig at the Stardust Ballroom—but they never quite came off right. We weren’t considered hip by the bands in that scene, because they thought of us as a glam outfit from the Troubadour side of town more than we ever really were. What those bands didn’t know is that we were probably darker and more sinister than they were. Nor did they realize that we could not fucking stand our peers on the other side of town.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: