По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

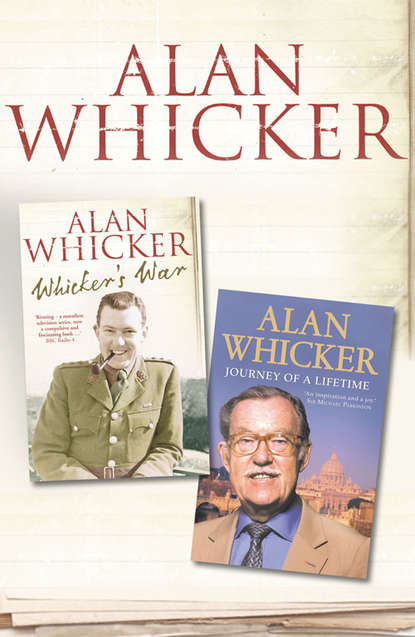

Whicker’s War and Journey of a Lifetime

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

A handful of small Italian tanks did attempt a few brave sorties but their 37mm guns had no chance against Shermans with 75s and heavy armour.

Fifteen miles from the landing beaches, our first capture on the road north to Syracuse and Catania was Noto, once capital of the region and Sicily’s finest baroque town. Thankfully it was absolutely untouched by war, and bisected by one tree-lined avenue which climbed from the plain up towards the town square and down the other side. We did not know whether this approach had been cleared of enemy and mines, so advanced carefully.

The population emerged equally cautiously, and lined the road. Then they started, hesitantly, to clap – a ripple of applause that followed us into their town.

You clap if you’re approving, without being enthusiastic. Nobody cheered – the welcome was restrained. We were not kissed once – nothing so abandoned. It seemed they didn’t quite know how to handle being conquered.

Like almost every other village and town we were to reach, Noto’s old walls were covered with Fascist slogans. Credere! Obbedire! Combattere! – Believe! Obey! Fight! – was popular, though few of the locals seemed to have got its message. Another which never ceased to irritate me was Il Duce ha sempre ragione – The Leader is always right! Shades of Big Brother to come. Hard to think of a less-accurate statement; we were in Sicily to point out the error in that argument.

Another even less-imaginative piece of propaganda graffiti was just ‘DUCE’, painted on all visible surfaces. As a hill town came in to focus every wall facing the road would be covered with Duces. Such scattergun publicity was a propaganda tribute to Mussolini, the Dictator who by then had already become the victim of his own impotent fantasies. To me he always appeared more a clown than a threat. To his prisoners he was no joke.

In Noto the baroque Town Hall and Cathedral faced each other, giving us a taste of what war-in-Italy was to become: it would be like fighting through a museum.

We filmed one small unexpected ceremony with a carabinieri officer who had discovered a copy of a 1940 speech to the Italians by Churchill. From the steps of the Casa del Fascio he read it out with many a verbal flourish; an intent audience nodded thoughtfully. Churchill had been promoted from ogre to statesman overnight.

Then three British officers arrived and marched up to the town’s War Memorial, where after a respectful silence they gave a formal salute to the commemorated townsfolk who had fallen as our Allies in the Great War. That sensitive and sensible gesture went down very well, and for the first time the applause was real. You could see the Sicilians thinking, ‘Maybe they’re going to be all right, after all!’

Observing both sides in action, I had by now seen enough of the war and the military to appreciate that if you had to be in the army, a film unit was the place to be. It offered as much excitement as you could handle – in some cases, rather more – but also a degree of independence, and even an unmilitary acknowledgement which cut through rank.

We’re all susceptible to cameras, though we may pretend to be disinterested and impatient. (Surely you don’t want to take my picture?) In truth, everyone from General Montgomery down was delighted to be photographed. I spent some time with him during the war and always, as soon as he saw me, he’d start pointing at nothing in particular, but in a most commanding manner. It was his way and it seemed to work; half-a-century ago he had television-style fame, before television.

People do straighten up and pull-in their stomachs when a camera appears. It’s an instant reflex – like beauty queens, for instance. As soon as they see a camera, they smile and wave.

Senior army officers were certainly not given to waving but, not quite understanding what we were doing, tended to approach us with impatient exasperation or amused confusion. Usually when they saw we were quite professional they would submit to direction or just leave us alone – which for a junior officer, was ideal.

We drove north and found the 7th Green Howards had captured a large Italian coastal defence position of 12-inch gun-howitzers which could throw a 6101b shell 20 miles. They were pointing towards our carefree arrival route and positioned to do terrible damage to any invader, but were only as good as their crews – who fortunately were not working that day.

We noticed with some bitterness towards international Arms Kings that they had been manufactured by British Vickers-Armstrong. Our 74th Field Regiment got them firing on German positions outside Catania, the biggest guns the Eighth Army had ever operated – so I suppose it worked out all right in the end.

Another capture worked out equally well, and Sergeant S.A. Gladstone got some expressive pictures of happy troops liberating cellars containing 7,000 gallons of good red wine. As trophies go, this was vintage and generally accepted as even better booty than tomatoes.

After our carefree advance from the beach, resistance had toughened in front of the Eighth Army. German paratroops had been flown in from France and the Hermann Goering Division replaced the timid and apathetic Italians. After tough fighting on the beaches, the Americans enjoyed an easier run through east and central Sicily, then followed the Germans around the giant sentinel of Mount Etna as they pulled back and prepared to retreat to the mainland.

As for our enemies, we soon discovered that the Italians in their rickety little tanks were anxious to become our prisoners, and the Germans in their enormous 57-ton Tiger tanks were anxious to kill us – so at least we knew where we were …

Sergeant Radford and I set off across the island to be in at the capture of Palermo by General Patton’s army. That pugnacious American General had just been in deep trouble after visiting a hospital where he slapped and abused two privates he believed were malingering. The soldiers were said to be suffering, like the rest of us, from ‘battle fatigue’. They had no wounds though one was found to have mild dysentery, yet they seriously affected the war. Patton’s exasperation was demonstrated in front of an accompanying War Correspondent, and the resultant Stateside publicity put the General’s career on hold for a year – and in due course provided a tragic death-knell for Churchill’s Anzio campaign, which needed Patton’s drive and leadership.

As we drove through remote and untouched mountain villages, we were the first Allied soldiers they had seen. Wine was pressed upon us and haircuts (including a friction) cost a couple of cigarettes. Even the almost unsmokable ‘V’ cigarettes made for the Eighth Army in India were eagerly bartered.

In Palermo householders peeped timidly around their curtains, wondering whether our dust-covered khaki was field-grey? The city was peaceful – blue trams were running and the police with swords and tricornes drifted about, as well dressed as Napoleonic officers.

After an RAF visit, the harbour was full of half-sunken gunboats, each surrounded by shoals of large fish. We caught a few by hitting them with stones. Izaac Walton must have been spinning.

Posters showed a monstrous John Bull, the world his rounded stomach as he swallowed more lands. Another was of a grinning skeleton in a British steel helmet. I took pictures of them while passers-by hurried on, fearful lest I turn and blame them.

We returned across Sicily to the Eighth Army HQ on the malarial Lentini plain – indeed a large number of our casualties were from mosquitoes. During the night we felt huge shuddering explosions outside Catania and watched sheets of flame light the sky. The Germans were blowing-up their ammunition dumps – so they were about to start their escape to the mainland.

A new officer had arrived to join us: Lieutenant A.Q. McLaren who, captured in the desert by Rommel’s Afrika Korps while using two cameras, had refused to hand one over because it was personal property and demanded a receipt for the War Office Ikonta. He later escaped, still carrying the receipt.

As we were meeting, an operational message came in saying that Catania was about to fall. We scrambled off to get the pictures. McLaren was driving ahead of me, standing up in the cab of his truck watching for enemy aircraft, as we all had to. This gave a few seconds’ warning if the Luftwaffe swooped down to strafe the road.

We drove in column around the diversion at reeking Dead Horse Corner. In the dust ahead lay a German mine. McLaren’s warning scream came too late. It was his first day in Sicily.

The patient infantry plodding past us moved on silently towards the city. They had seen another violent death and perhaps they too would soon stop a bullet or a shellburst. In an hour or so some of them would also be dead, and they knew it.

The whole direction of their lives now was to reach some unknown place and, if possible, kill any unknown Germans they found there. In battle, death is always present and usually unemotional, and when it approaches, inches can mean the march goes on – or you are still and resting, for ever.

However its proximity does wipe away life’s other problems. Those plodding figures passing Dead Horse Corner and McLaren’s body were not worrying about unpaid bills or promotion or nagging wives or even sergeant majors. Getting through the day alive was achievement enough.

It took the population of Catania some time to realise that the Germans had gone. Then they came out into the streets to cheer and show their relief, carrying flowers, fruit, wine … It was hard to see them as enemies. Our pictures showed Italian nurses tending the wounded of the Durham Light Infantry.

At this point Sergeants Herbert and Travis arrived and unintentionally captured Catania’s entire police force. This was not in the shot-list. They had left their jeep behind a blown bridge on the road into town and were filming on foot when a civilian car came out of the city towards them. Surprised by such an apparition in a war zone, they commandeered it and ordered the driver to turn round and take them into Catania.

Speeding ahead of the Army, he whizzed excitedly along back streets and finally through two huge gates into a palace courtyard full of armed carabinieri. As the gates slammed behind them and they looked around at massed uniforms … suspicion dawned that now they might be the prisoners.

Then the Commandant in an elegant uniform arrived, saluted, and asked for their orders. That was better. They ventured that they were just a couple of photographers who did not really want a police force, not just then. However, they did want transport.

They were instantly ushered into a large garage crammed with every type of vehicle, their choice was filled with petrol and the ignition key presented with a flourish. Amid salutes, the conquering sergeants drove out through the massive gates, at speed. Honour had been satisfied on all sides.

The object of much planning-ahead during the final fighting through Sicily was not the capture of Messina, straddling the enemy’s escape route and well-protected by Kesselring’s massed anti-aircraft guns, but of Taormina, an hour’s drive to its south. This charming honeymoon-village of the Twenties climbs the rocky coast in the shadow of Mount Etna’s 11,000 feet. Like Capri, its flowers, pretty villas and bright social life gave it a sort of Noël Coward appeal. It was untouched by war, of course, as all armies protect places they might wish to use as headquarters, or billets.

It was a placid scene, as we arrived. Out in the bay a British gunboat lay peacefully at anchor, while a number of anxious Italian soldiers were standing on the beach trying to surrender to it. They would probably have been almost as satisfied if anyone else had paused to capture them – even a passing Film Unit – but by this time we had all become rather blasé about Italian prisoners. They had lost their scarcity value.

My CO Geoffrey Keating and our War Artist friend Edward Ardizzone had reached Taormina ahead of the army patrols. I was surprised poor old Ted could climb the mountainside because he seemed to be overweight and getting on a bit – he was at least 40. However he struggled up the 800 feet from the seashore – not as elegantly as Noël arriving at the beginning of Act 2 but in time for them to requisition, breathlessly, the Casa Cuseni. This splendid little villa built of golden stone was owned before the war by an expatriate British artist. Its garden was heady with the exotic scent of orange blossom, its library equally heady with pornography.

Despite those distractions, the defeat of the Germans in Sicily meant that we at last had time to be happy, even as we prepared for the coming invasion of the mainland. Every evening we relaxed with a Sicilian white in the hush of the garden terrace as the sun set behind Mount Etna. This was war at its best…

The 10,000 square miles of Sicily had been captured in 38 days, during which the Allies suffered 31,158 casualties. The Wehrmacht had lost 37,000 men, the Italians 130,000 – most of them, of course, prisoners getting out of the war alive.

In its successful strategic withdrawal, the German army corps had little air and no naval support, yet its 60,000 men stood up to two Allied armies of 450,000 men – and finally some 55,000 of them escaped across the Straits of Messina to Italy to fight another day. They took with them 10,000 vehicles and 50 tanks. Generalfeldmarschall Kesselring – the troops called him ‘Laughing Albert’ – had enough to laugh about at this Dunkirk victory.

Our last pictures of the Sicilian campaign showed Generals Eisenhower and Montgomery staring symbolically through field glasses out across the Straits of Messina towards the toe of Italy, and the enemy. That was to be our next step towards the end of the war. Behind them in Sicily, an Allied military government was being established, though in fact control of the island was falling back through the years into the hands of the island’s secret army – the Mafia.

Our victory was darkened by the fact that behind the scenes – and with the very best of intentions, you understand – the Americans were handing Sicily back to its former masters. In a misguided military decision, they enlisted the Godfather!

From his prison cell in New York State, Lucky Luciano, then Capo di tutti Capi, arranged Mafia support and guidance for the Allies in Sicily – in return of course for various business concessions. So it was that Lucky was released from prison and flown-back to his homeland to ‘facilitate the invasion’ – and on the side, to set-up the Mafia’s new narcotics empire. Vito Genovese, well-known New York hoodlum wanted for murder and various crimes in America, turned up in uniform in Sicily as a liaison officer attached to the US Army. Through threats and graft and skill, their contingent soon out-manoeuvred our unworldly do-gooding AMGOT, the Allied Military Government of Occupied Territory. We had our card marked by gangsters.

Thus the victors helped destroy Mussolini’s rare achievement; he had held the Mafia down and all-but destroyed its power. Now in their rush to pacify an island already peaceful, the Americans resuscitated another convicted Mafiosi, Don Calò Vizzini, and put him in control of the island’s civil Administration with military vehicles and supplies at his disposal. The Mafia was born again, fully grown.

Since then even Italian Prime Ministers have been found to enjoy such connections and support. For example, the 113-mile Palermo to Messina autostrada was finally inaugurated after 35 years by Silvio Berlusconi in December 2004. It cost £500 million and was partly funded by Brussels and the European Investment Bank. Work had begun in 1969 and, following the regular siphoning-off of materials and funds by the Mafia, proceeded at a rate of three miles a year.

Fortunately for our lively sense of mission, we simple soldiers in our shining armour knew nothing of the Mafia’s rebirth, nor could we foresee it. We had no time to occupy ourselves with the future crime and corruption that was to inherit our victory. We were busy fighting a war and preparing for an attack on Italy’s mainland.

So the Allies left five million Sicilians to a future often controlled by the Mafia, and a resigned tourist industry which in the peacetime-to-come would advertise: ‘Invade Sicily – everyone else has …’

At the end of August, the only Germans left in Sicily were the 7,000 ruminating behind barbed wire. General Montgomery’s headquarters in the San Domenico, former convent and now the grandest hotel in Taormina, prepared for the first visit of the Allied Commander of the Mediterranean Theatre, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, then almost unknown outside the US – and little-known within it.

An American Supreme Commander with all those stars was something quite new to us, so he was accorded the full military razzle-dazzle and then some, as only the British Army knows how to lay on.