По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

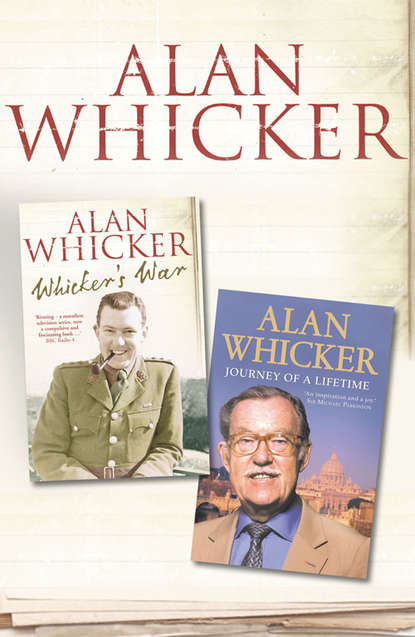

Whicker’s War and Journey of a Lifetime

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Looking through the wine list for something interesting with which to toast his bride, Geoffrey settled for a cider, assuming it to be the softest of drinks and better with fish than a coke. After several country ciders he moved unsteadily towards the marriage bed, and from then on his life and social consumption changed direction. He never looked back – and his wife never forgave me.

At Anzio I went with him around our front-line positions and suddenly noticed that, while we were driving in his open jeep along an embankment, laughing and chatting, we were on the dreaded Lateral Road where nothing else moved. I remembered tanks rarely ventured along it in daylight because of heavy enemy artillery fire and German machine guns with sights locked-on to any movement.

We were looking for a Company HQ. There was no other traffic. Then I saw a few soldiers in the dugout positions below us. They were moving at a crouch or lying looking up at us as we drove happily along, an apparition in a no-go area. Just before the firing began, I realised we were not travelling sensibly.

Needless to say Geoffrey’s reaction to possible death and destruction was so indifferent and outrageous that we emerged unscathed and drove on, still finding something or other funny; doubtless my growing panic.

I found out afterwards that Geoffrey would go to sleep in his dentist’s chair during treatment. By then I had registered one firm Unit rule which saw me through the war: separate jeeps.

The bridgehead solidified along 16 miles of coast and about seven miles inland – say just over 100 square miles. I’ve known bigger farms. Some 20,000 Italian civilians had been shipped back to Naples, leaving Anzio a small and desperate military state and a throwback to the Great War days of static warfare, shelled all day and bombed all night. There was no hiding place at Anzio.

On most warfronts there is a calm secure area at the rear where the wounded can be taken, where units rest when they come out of the line and Generals may sleep comfortably. On the bridgehead there were no safe areas. You were never out of range.

Indeed soldiers at the front would sometimes refuse to report minor wounds which might mean they would be sent back to a field hospital – and so into the heavy artillery target area. Provided it was not a major battle they often felt more secure at the front, where the war was personal and the percentages could more easily be calculated.

Keating and I invited a number of friendly War Correspondents to escape from the barren Press camp next door and join us in our more substantial villa, which in our days of bombardment had already been recognised as Lucky. They included one of the Rabelaisian characters of our war, Reynolds Packard. In peaceful days he had been Rome Correspondent of the Chicago Tribune, and with his wife Eleanor had written a well-tided book on Mussolini, ‘Balcony Empire’. He was knowledgeable, sociable and excellent company but had, we discovered, one foible liable to render him untouchable – even in our Mess.

The villa’s sitting room, where we played poker and sometimes even worked, overlooked the sea and so faced away from arriving shells. It was always pleasantly crowded and noisy enough to discourage the rats, so this was where we set-up our camp beds each night. Reynolds, a portly funny figure, was a notable non-teetotaller and so able to sleep through most bombardments. His only lack of social grace was revealed when he woke in the night and needed to urinate. In the unfamiliar darkness he would struggle out of his bed – and pee wherever he stood.

He had been campaigning too long in open country, sleeping in too many fields without the benefit of indoor sanitation and his behaviour pattern had become lax, not to mention disgusting. Not too many people wanted the bed space next to him.

Such a reaction to a full bladder might be acceptable in a foxhole or on a beach, but was less welcome in our new Mess. After the deluge a chastened Packard would face fury in the morning. He could not deny the offence because the evidence was all too obvious. He was always horrified and full of remorse, blamed demon vino and swore it would never happen again. Next night, it would.

In the early hours we would awake to the sound of running water hitting the tiles. The first weary automatic move in the darkness was to lean down, rescue shoes, put them in the dry zone on the end of the bed, and go back to sleep. In the morning, an uproar of protest, another furious inquest and more craven apologies. The distasteful procedure was in danger of becoming normal.

Packard’s momentary forgetfulness in the darkness of a strange room was not excusable – though perhaps understandable to those living on a war front where the niceties of civilised life could fall away. After some months campaigning in the field and living basically I committed a graceless mistake myself, which still haunts me.

We had been advancing slowly through Tuscany and sleeping rough; but once Florence fell some old friends invited me to a welcome party in their magnificent apartment on the Lungarno, overlooking the river. During that elegant evening in the sunlit drawing room I remember needing to stub out my cigarette. Seeing no ashtrays in the salon, I dropped it on to the deep-pile carpet and punctiliously ground it out with my toe – as one would.

As I turned to continue the conversation I had an uneasy feeling something was not quite right … but could not recollect what it might be.

It was not until later that night when my hostess upbraided me – ‘I saw you’ – that I was struck by the vast distance between surviving on a hillside, and living amid glowing Renaissance treasures. I had become one of the brutal and licentious. I paid in flowers, shame and guilt.

The free spirit of Reynolds Packard was even less socially acceptable, but eventually threats of expulsion began to wear him down, or dry him up. After a couple of weeks struggling with him and with the strengthening Wehrmacht now surrounding us, we were becoming familiar with the death-defying routines of life in an encircled battlefield – the deep daily depression that appeared each dawn. So Geoffrey and I decided it was time to attempt to be more social and civilised. Some warriors’ relaxation would improve morale: we had mugs, a few glasses, we had whisky, gin and local vino; we even had American saltines and processed cheese. All told, our first party was indicated – the kind of promising social adventure that could make Anzio just endurable.

The one imperative for such a gathering was of course female – beyond price and almost impossible to discover in such a war zone. Almost, but not totally. The vast and impressive US 95th Evacuation Hospital had just established its dark green marquees with big red crosses, and the more secure stone squares covered with tarpaulins, along the coast-road to the south. It was decided that I should approach the Matron and offer her nurses the freedom of our Mess for one evening. Such an hospitable international gesture was the least we could do.

Making Matron see the good sense of this project was not easy, even at Anzio – particularly at Anzio – but fortunately even in those days celebrity had become a strong selling-point, and American War Correspondents were national names. Hollywood made films about them, wearing trench coats and Holding the Front Page and being gallant. Before the pleasantly businesslike Matron I dropped the famous names that were sleeping on our floor – though excluded Packard, just in case the word had got round. When I later drove triumphantly across to the hospital reception, there waited half-a-dozen jolly off-duty nurses and Red Cross girls evidently quite ready to raise our spirits and briefly escape their endless and harrowing lines of casualties.

They piled happily into the jeep and we returned to our Mess, to find it tidily rearranged, bottles opened expectantly – and the tough swaggering Correspondents surprisingly shy. We passed an excellent evening, discussed everything except the war, drank everything available, and much appreciated the company of pleasant young women in their fatigues and make-up who had made an effort to become glowing replicas of peacetime party-goers. During the evening the spasmodic shelling was so commonplace it hardly interrupted conversation. Packard was on his best behaviour, being suave in a world-weary WarCo way. You would never have guessed.

We planned future escapes for them, said our farewells affectionately, and I drove them back to the 95th Evac … where in stunned horror we confronted havoc and disaster. A damaged Luftwaffe aircraft about to crash-land had jettisoned five antipersonnel bombs across the hospital’s tented lines. These killed three nurses and a Red Cross girl in their Mess tent, along with 22 staff and patients, and wounded 60 others. The place became known as Hell’s Half Acre.

THEY DIED WITHOUT ANYONE EVEN KNOWING THEIR NAMES… (#ulink_35dbb036-7f38-51b8-a011-5a5f84dcd620)

Anzio and Cassino were planned as the twin military pinnacles of our Italian campaign; instead they became tragic examples of Allied Generalship at its most disastrous.

After the US VI Corps had enjoyed a classic and almost uncontested assault landing on the Anzio beaches, General Lucas decided that his 50,000 men – plus me – should dig-in and wait indefinitely for reinforcements, before considering any attack. This condemned us to a probable Dunkirk, or at best a struggle for survival amid the dead hopes of a Roman liberation. The Anzio landing had been intended to end the Cassino deadlock but instead of riding gallantly to their rescue, we now hoped someone would come and rescue us.

At the other end of this comatose Allied pincer movement, an even more disastrous international decision was taken by Field Marshal Alexander, supported by Generals Freyberg and Clark. In four hours, 239 heavy and medium bombers of Major General Nathan F. Twining’s Mediterranean Allied Strategic Air Force dropped 453½ tons of bombs on the glorious Benedictine monastery of Monte Cassino. Each Flying Fortress carried twelve 5001b demolition bombs.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: