По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

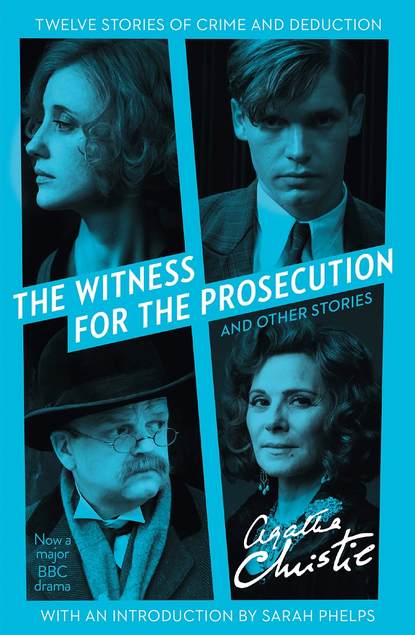

The Witness for the Prosecution: And Other Stories

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Who’s bothering?’

‘I thought you were.’

‘Not at all.’

‘The thing’s over and done with,’ summed up the captain. ‘If Mrs Merrowdene at one time of her life was unfortunate enough to be tried and acquitted for murder—’

‘It’s not usually considered unfortunate to be acquitted,’ put in Evans.

‘You know what I mean,’ said Captain Haydock irritably. ‘If the poor lady has been through that harrowing experience, it’s no business of ours to rake it up, is it?’

Evans did not answer.

‘Come now, Evans. The lady was innocent—you’ve just said so.’

‘I didn’t say she was innocent. I said she was acquitted.’

‘It’s the same thing.’

‘Not always.’

Captain Haydock, who had commenced to tap his pipe out against the side of his chair, stopped, and sat up with a very alert expression.

‘Hallo—allo—allo,’ he said. ‘The wind’s in that quarter, is it? You think she wasn’t innocent?’

‘I wouldn’t say that. I just—don’t know. Anthony was in the habit of taking arsenic. His wife got it for him. One day, by mistake, he takes far too much. Was the mistake his or his wife’s? Nobody could tell, and the jury very properly gave her the benefit of the doubt. That’s all quite right and I’m not finding fault with it. All the same—I’d like to know.’

Captain Haydock transferred his attention to his pipe once more.

‘Well,’ he said comfortably. ‘It’s none of our business.’

‘I’m not so sure …’

‘But surely—’

‘Listen to me a minute. This man, Merrowdene—in his laboratory this evening, fiddling round with tests—you remember—’

‘Yes. He mentioned Marsh’s test for arsenic. Said you would know all about it—it was in your line—and chuckled. He wouldn’t have said that if he’d thought for one moment—’

Evans interrupted him.

‘You mean he wouldn’t have said that if he knew. They’ve been married how long—six years you told me? I bet you anything he has no idea his wife is the once notorious Mrs Anthony.’

‘And he will certainly not know it from me,’ said Captain Haydock stiffly.

Evans paid no attention, but went on:

‘You interrupted me just now. After Marsh’s test, Merrowdene heated a substance in a test-tube, the metallic residue he dissolved in water and then precipitated it by adding silver nitrate. That was a test for chlorates. A neat unassuming little test. But I chanced to read these words in a book that stood open on the table:

“H

SO

decomposes chlorates with evolution of CL

O

. If heated, violent explosions occur; the mixture ought therefore to be kept cool and only very small quantities used.”

Haydock stared at his friend.

‘Well, what about it?’

‘Just this. In my profession we’ve got tests too—tests for murder. There’s adding up the facts—weighing them, dissecting the residue when you’ve allowed for prejudice and the general inaccuracy of witnesses. But there’s another test of murder—one that is fairly accurate, but rather—dangerous! A murderer is seldom content with one crime. Give him time, and a lack of suspicion, and he’ll commit another. You catch a man—has he murdered his wife or hasn’t he?—perhaps the case isn’t very black against him. Look into his past—if you find that he’s had several wives—and that they’ve all died shall we say—rather curiously?—then you know! I’m not speaking legally, you understand. I’m speaking of moral certainty. Once you know, you can go ahead looking for evidence.’

‘Well?’

‘I’m coming to the point. That’s all right if there is a past to look into. But suppose you catch your murderer at his or her first crime? Then that test will be one from which you get no reaction. But suppose the prisoner is acquitted—starting life under another name. Will or will not the murderer repeat the crime?’

‘That’s a horrible idea!’

‘Do you still say it’s none of our business?’

‘Yes, I do. You’ve no reason to think that Mrs Merrowdene is anything but a perfectly innocent woman.’

The ex-inspector was silent for a moment. Then he said slowly:

‘I told you that we looked into her past and found nothing. That’s not quite true. There was a stepfather. As a girl of eighteen she had a fancy for some young man—and her stepfather exerted his authority to keep them apart. She and her stepfather went for a walk along a rather dangerous part of the cliff. There was an accident—the stepfather went too near the edge—it gave way, and he went over and was killed.’

‘You don’t think—’

‘It was an accident. Accident! Anthony’s overdose of arsenic was an accident. She’d never have been tried if it hadn’t transpired that there was another man—he sheered off, by the way. Looked as though he weren’t satisfied even if the jury were. I tell you, Haydock, where that woman is concerned I’m afraid of another—accident!’

The old captain shrugged his shoulders.

‘It’s been nine years since that affair. Why should there be another “accident”, as you call it, now?’

‘I didn’t say now. I said some day or other. If the necessary motive arose.’

Captain Haydock shrugged his shoulders.

‘Well, I don’t know how you’re going to guard against that.’

‘Neither do I,’ said Evans ruefully.

‘I should leave well alone,’ said Captain Haydock. ‘No good ever came of butting into other people’s affairs.’

But that advice was not palatable to the ex-inspector. He was a man of patience but determination. Taking leave of his friend, he sauntered down to the village, revolving in his mind the possibilities of some kind of successful action.