По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

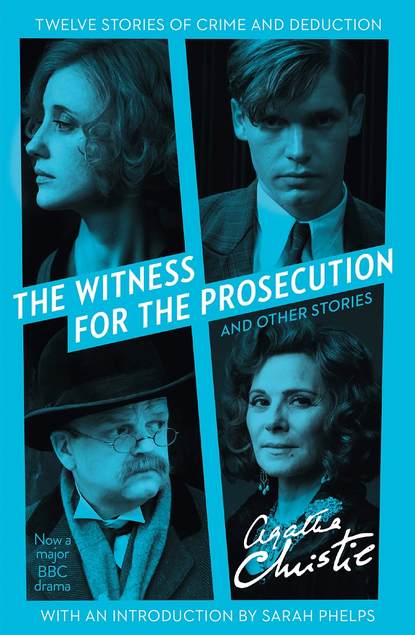

The Witness for the Prosecution: And Other Stories

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘So it’s you, dearie,’ she said, in a wheezy voice. ‘Nobody with you, is there? No playing tricks? That’s right. You can come in—you can come in.’

With some reluctance the lawyer stepped across the threshold into the small dirty room, with its flickering gas jet. There was an untidy unmade bed in a corner, a plain deal table and two rickety chairs. For the first time Mr Mayherne had a full view of the tenant of this unsavoury apartment. She was a woman of middle age, bent in figure, with a mass of untidy grey hair and a scarf wound tightly round her face. She saw him looking at this and laughed again, the same curious toneless chuckle.

‘Wondering why I hide my beauty, dear? He, he, he. Afraid it may tempt you, eh? But you shall see—you shall see.’

She drew aside the scarf and the lawyer recoiled involuntarily before the almost formless blur of scarlet. She replaced the scarf again.

‘So you’re not wanting to kiss me, dearie? He, he, I don’t wonder. And yet I was a pretty girl once—not so long ago as you’d think, either. Vitriol, dearie, vitriol—that’s what did that. Ah! but I’ll be even with ’em—’

She burst into a hideous torrent of profanity which Mr Mayherne tried vainly to quell. She fell silent at last, her hands clenching and unclenching themselves nervously.

‘Enough of that,’ said the lawyer sternly. ‘I’ve come here because I have reason to believe you can give me information which will clear my client, Leonard Vole. Is that the case?’

Her eyes leered at him cunningly.

‘What about the money, dearie?’ she wheezed. ‘Two hundred quid, you remember.’

‘It is your duty to give evidence, and you can be called upon to do so.’

‘That won’t do, dearie. I’m an old woman, and I know nothing. But you give me two hundred quid, and perhaps I can give you a hint or two. See?’

‘What kind of hint?’

‘What should you say to a letter? A letter from her. Never mind now how I got hold of it. That’s my business. It’ll do the trick. But I want my two hundred quid.’

Mr Mayherne looked at her coldly, and made up his mind.

‘I’ll give you ten pounds, nothing more. And only that if this letter is what you say it is.’

‘Ten pounds?’ She screamed and raved at him.

‘Twenty,’ said Mr Mayherne, ‘and that’s my last word.’

He rose as if to go. Then, watching her closely, he drew out a pocket book, and counted out twenty one-pound notes.

‘You see,’ he said. ‘That is all I have with me. You can take it or leave it.’

But already he knew that the sight of the money was too much for her. She cursed and raved impotently, but at last she gave in. Going over to the bed, she drew something out from beneath the tattered mattress.

‘Here you are, damn you!’ she snarled. ‘It’s the top one you want.’

It was a bundle of letters that she threw to him, and Mr Mayherne untied them and scanned them in his usual cool, methodical manner. The woman, watching him eagerly, could gain no clue from his impassive face.

He read each letter through, then returned again to the top one and read it a second time. Then he tied the whole bundle up again carefully.

They were love letters, written by Romaine Heilger, and the man they were written to was not Leonard Vole. The top letter was dated the day of the latter’s arrest.

‘I spoke true, dearie, didn’t I?’ whined the woman. ‘It’ll do for her, that letter?’

Mr Mayherne put the letters in his pocket, then he asked a question.

‘How did you get hold of this correspondence?’

‘That’s telling,’ she said with a leer. ‘But I know something more. I heard in court what that hussy said. Find out where she was at twenty past ten, the time she says she was at home. Ask at the Lion Road Cinema. They’ll remember—a fine upstanding girl like that—curse her!’

‘Who is the man?’ asked Mr Mayherne. ‘There’s only a Christian name here.’

The other’s voice grew thick and hoarse, her hands clenched and unclenched. Finally she lifted one to her face.

‘He’s the man that did this to me. Many years ago now. She took him away from me—a chit of a girl she was then. And when I went after him—and went for him too—he threw the cursed stuff at me! And she laughed—damn her! I’ve had it in for her for years. Followed her, I have, spied upon her. And now I’ve got her! She’ll suffer for this, won’t she, Mr Lawyer? She’ll suffer?’

‘She will probably be sentenced to a term of imprisonment for perjury,’ said Mr Mayherne quietly.

‘Shut away—that’s what I want. You’re going, are you? Where’s my money? Where’s that good money?’

Without a word, Mr Mayherne put down the notes on the table. Then, drawing a deep breath, he turned and left the squalid room. Looking back, he saw the old woman crooning over the money.

He wasted no time. He found the cinema in Lion Road easily enough, and, shown a photograph of Romaine Heilger, the commissionaire recognized her at once. She had arrived at the cinema with a man some time after ten o’clock on the evening in question. He had not noticed her escort particularly, but he remembered the lady who had spoken to him about the picture that was showing. They stayed until the end, about an hour later.

Mr Mayherne was satisfied. Romaine Heilger’s evidence was a tissue of lies from beginning to end. She had evolved it out of her passionate hatred. The lawyer wondered whether he would ever know what lay behind that hatred. What had Leonard Vole done to her? He had seemed dumbfounded when the solicitor had reported her attitude to him. He had declared earnestly that such a thing was incredible—yet it had seemed to Mr Mayherne that after the first astonishment his protests had lacked sincerity.

He did know. Mr Mayherne was convinced of it. He knew, but had no intention of revealing the fact. The secret between those two remained a secret. Mr Mayherne wondered if some day he should come to learn what it was.

The solicitor glanced at his watch. It was late, but time was everything. He hailed a taxi and gave an address.

‘Sir Charles must know of this at once,’ he murmured to himself as he got in.

The trial of Leonard Vole for the murder of Emily French aroused widespread interest. In the first place the prisoner was young and good-looking, then he was accused of a particularly dastardly crime, and there was the further interest of Romaine Heilger, the principal witness for the prosecution. There had been pictures of her in many papers, and several fictitious stories as to her origin and history.

The proceedings opened quietly enough. Various technical evidence came first. Then Janet Mackenzie was called. She told substantially the same story as before. In cross-examination counsel for the defence succeeded in getting her to contradict herself once or twice over her account of Vole’s association with Miss French. He emphasized the fact that though she had heard a man’s voice in the sitting-room that night, there was nothing to show that it was Vole who was there, and he managed to drive home a feeling that jealousy and dislike of the prisoner were at the bottom of a good deal of her evidence.

Then the next witness was called.

‘Your name is Romaine Heilger?’

‘Yes.’

‘You are an Austrian subject?’

‘Yes.’

‘For the last three years you have lived with the prisoner and passed yourself off as his wife?’

Just for a moment Romaine Heilger’s eye met those of the man in the dock. Her expression held something curious and unfathomable.

‘Yes.’

The questions went on. Word by word the damning facts came out. On the night in question the prisoner had taken out a crowbar with him. He had returned at twenty minutes past ten, and had confessed to having killed the old lady. His cuffs had been stained with blood, and he had burned them in the kitchen stove. He had terrorized her into silence by means of threats.