По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

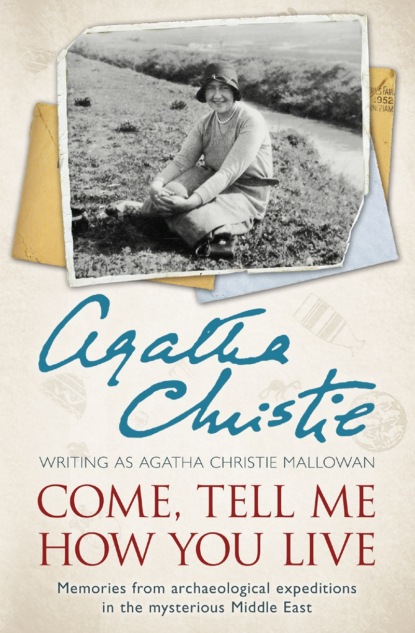

Come, Tell Me How You Live: An Archaeological Memoir

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

However, I wake up an hour later, feeling perfectly restored and eager to see what can be seen.

Mac, even, for once submits to being torn from his diary.

We go out sight-seeing, and spend a delightful afternoon.

When we are at the farthest point from the Hotel we run into the party of French people. They are in distress. One of the women, who is wearing (as all are) high-heeled shoes, has torn off the heel of her shoe, and is faced with the impossibility of walking back the distance to the Hotel. They have driven out to this point, it appears, in a taxi, and the taxi has now broken down. We cast an eye over it. There appears to be but one kind of taxi in this country. This vehicle is indistinguishable from ours—the same dilapidated upholstery and general air of being tied up with string. The driver, a tall, lank Syrian, is poking in a dispirited fashion into the bonnet.

He shakes his head. The French party explain all. They have arrived here by ’plane yesterday, and will leave the same way tomorrow. This taxi they have hired for the afternoon at the Hotel, and now it has broken down. What will poor Madame do? ‘Impossible de marcher, n’est ce pas, avec un soulier seulement.’

We pour out condolences, and Max gallantly offers our taxi. He will return to the Hotel and bring it out here. It can make two journeys and take us all back.

The suggestion is received with acclamations and profuse thanks, and Max sets off.

I fraternize with the French ladies, and Mac retires behind an impenetrable wall of reserve. He produces a stark ‘Oui’ or ‘Non’ to any conversational openings, and is soon mercifully left in peace. The French ladies profess a charming interest in our journeyings.

‘Ah, Madame, vous faites le camping?’

I am fascinated by the phrase. Le camping! It classes our adventure definitely as a sport!

How agreeable it will be, says another lady, to do le camping.

Yes, I say, it will be very agreeable.

The time passes; we chat and laugh. Suddenly, to my great surprise, Queen Mary comes lurching along. Max, with an angry face, is at the wheel.

I demand why he hasn’t brought the taxi?

‘Because,’ says Max furiously, ‘the taxi is here.’ And he points a dramatic finger at the obdurate car, into which the lank Syrian is still optimistically peering.

There is a chorus of surprised exclamations, and I realize why the car has looked so familiar! ‘But,’ cries the French lady, ‘this is the car we hired at the Hotel.’ Nevertheless, Max explains, it is our taxi.

Explanations with Aristide have been painful. Neither side has appreciated the other’s point of view.

‘Have I not hired the taxi and you for three months?’ demands Max. ‘And must you let it out to others behind my back in this shameful way?’

‘But,’ says Aristide, all injured innocence, ‘did you not tell me that you yourself would not use it this afternoon? Naturally, then, I have the chance to make a little extra money. I arrange with a friend, and he drives this party round Palmyra. How can it injure you, since you do not want to sit in the car yourself?’

‘It injures me,’ replies Max, ‘since in the first place it was not our arrangement; and in the second place the car is now in need of repair, and in all probability will not be able to proceed tomorrow!’

‘As to that,’ says Aristide, ‘do not disquiet yourself. My friend and I will, if necessary, sit up all night!’

Max replies briefly that they’d better.

Sure enough, the next morning the faithful taxi awaits us in front of the door, with Aristide smiling, and still quite unconvinced of sin, at the wheel.

Today we arrive at Der-ez-Zor, on the Euphrates. It is very hot. The town smells and is not attractive. The Services Spéciaux kindly puts some rooms at our disposal, since there is no European hotel. There is an attractive view over the wide brown flow of the river. The French officer inquires tenderly after my health and hopes I have not found motoring in the heat too much for me. ‘Madame Jacquot, the wife of our General, was complètement knock out when she arrived.’

The term takes my fancy. I hope that I, in my turn, shall not be complètement knock out by the end of our survey!

We buy vegetables and large quantities of eggs, and with Queen Mary full to the point of breaking her springs, we set off, this time to start on the survey proper.

Busaira! Here there is a police post. It is a spot of which Max has had high hopes, since it is at the junction of the Euphrates with the Habur. Roman Circesium is on the opposite bank.

Busaira proves, however, disappointing. There are no signs of any antique settlement other than Roman, which is treated with the proper disgust. ‘Min Ziman er Rum,’ says Hamoudi, shaking his head distastefully, and I echo him dutifully.

For to our point of view the Romans are hopelessly modern—children of yesterday. Our interest begins at the second millennium B.C., with the varying fortunes of the Hittites, and in particular we want to find out more about the military dynasty of Mitanni, foreign adventurers about whom little is known, but who flourished in this part of the world, and whose capital city of Washshukkanni has yet to be identified. A ruling caste of warriors, who imposed their rule on the country, and who intermarried with the Royal House of Egypt, and who were, it seems, good horsemen, since a treatise upon the care and training of horses is ascribed to a certain Kikkouli, a man of Mitanni.

And from that period backwards, of course, into the dim ages of pre-history—an age without written records, when only pots and house plans, and amulets, ornaments, and beads, remain to give their dumb witness to the life the people lived.

Busaira having been disappointing, we go on to Meyadin, farther south, though Max has not much hope of it. After that we will strike northward up the left bank of the Habur river.

It is at Busaira that I get my first sight of the Habur, which has so far been only a name to me—though a name that has been repeatedly on Max’s lips.

‘The Habur—that’s the place. Hundreds of Tells!’

He goes on: ‘And if we don’t find what we want on the Habur, we will on the Jaghjagha!’

‘What,’ I ask, the first time I hear the name, ‘is the Jaghjagha?’

The name seems to me quite fantastic!

Max says kindly that he supposes I have never heard of the Jaghjagha? A good many people haven’t, he concedes.

I admit the charge and add that until he mentioned it, I had not even heard of the Habur. That does surprise him.

‘Didn’t you know,’ says Max, marvelling at my shocking ignorance, ‘that Tell Halaf is on the Habur?’

His voice is lowered in reverence as he speaks of that famous site of prehistoric pottery.

I shake my head and forbear to point out that if I had not happened to marry him I should probably never have heard of Tell Halaf!

I may say that explaining the places where we dig to people is always fraught with a good deal of difficulty.

My first answer is usually one word—‘Syria’.

‘Oh!’ says the average inquirer, already slightly taken aback. A frown forms on his or her forehead. ‘Yes, of course—Syria…’ Biblical memories stir. ‘Let me see, that’s Palestine, isn’t it?’

‘It’s next to Palestine,’ I say encouragingly. ‘You know—farther up the coast.’

This doesn’t really help, because Palestine, being usually connected with Bible history and the lessons on Sunday rather than a geographical situation, has associations that are purely literary and religious.

‘I can’t quite place it.’ The frown deepens. ‘Whereabouts do you dig—I mean near what town?’

‘Not near any town. Near the Turkish and Iraq border.’

A hopeless expression then comes across the friend’s face.

‘But surely you must be near some town!’