По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

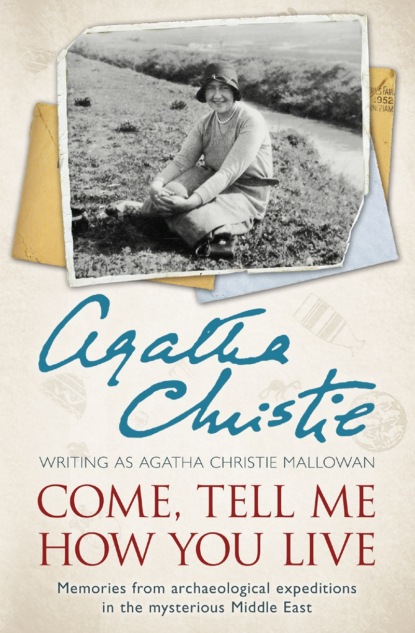

Come, Tell Me How You Live: An Archaeological Memoir

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘What is his number?’ I ask. The steward is immediately reproachful.

‘Madame! Mais c’est le charpentier du bateau!’

I become properly abashed—to reflect a few minutes later that that is not really an answer. Why, because he is the charpentier du bateau, does it make it any easier to pick him out from several hundred other blue-bloused men, all shouting: ‘Quatre-vingt treize?’ etc? His mere silence will not be sufficient identification. Moreover, does his being the charpentier du bateau enable him to pick out with unerring certainty one middle-aged Englishwoman from a whole crowd of middle-aged Englishwomen?

At this point in my reflections Max joins me, and says he has a porter for my luggage. I explain that the charpentier du bateau has taken mine, and Max asks why I let him. All the luggage should go together. I agree, but plead that my intellect is always weakened by sea-crossings. Max says: ‘Oh, well; we shall collect it all in the Douane.’ And we proceed to that inferno of yelling porters and to the inevitable encounter with the only type of really unpleasant Frenchwoman that exists—the Customs House Female; a being devoid of charm, of chic, of any feminine grace. She prods, she peers, she says, ‘Pas de cigarettes?’ unbelievingly, and finally, with a reluctant grunt, she scrawls the mystic hieroglyphics in chalk on our baggage, and we pass through the barrier and out on to the platform, and so to the Simplon Orient Express and the journey across Europe.

Many, many years ago, when going to the Riviera or to Paris, I used to be fascinated by the sight of the Orient Express at Calais and longed to be travelling by it. Now it has become an old familiar friend, but the thrill has never quite died down. I am going by it! I am in it! I am actually in the blue coach, with the simple legend outside: CALAIS–INSTANBUL. It is, undoubtedly, my favourite train. I like its tempo, which, starting Allegro con furore, swaying and rattling and hurling one from side to side in its mad haste to leave Calais and the Occident, gradually slows down in a rallentando as it proceeds eastwards till it becomes definitely legato.

In the early morning of the next day I let the blind up, and watch the dim shapes of the mountains in Switzerland, then the descent into the plains of Italy, passing by lovely Stresa and its blue lake. Then, later, into the smart station that is all we see of Venice and out again, and along by the sea to Trieste and so into Yugoslavia. The pace gets slower and slower, the stops are longer, the station clocks display conflicting times. H.E.O. is succeeded by C.E. The names of the stations are written in exciting and improbable-looking letters. The engines are fat and comfortable-looking, and belch forth a particularly black and evil smoke. Bills in the dining-cars are written out in perplexing currencies and bottles of strange mineral water appear. A small Frenchman who sits opposite us at table studies his bill in silence for some minutes, then he raises his head and catches Max’s eye. His voice, charged with emotion, rises plaintively: ‘Le change des Wagons Lits, c’est incroyable!’ Across the aisle a dark man with a hooked nose demands to be told the amount of his bill in (a) francs, (b) lire, (c) dinars, (d) Turkish pounds, (e) dollars. When this has been done by the long-suffering restaurant attendant, the traveller calculates silently and, evidently a master financial brain, produces the currency most advantageous to his pocket. By this method, he explains to us, he has saved fivepence in English money!

In the morning Turkish Customs officials appear on the train. They are leisurely, and deeply interested in our baggage. Why, they ask me, have I so many pairs of shoes? It is too many. But, I reply, I have no cigarettes, because I do not smoke, so why not a few more shoes? The douanier accepts the explanation. It appears to him reasonable. What, he asks, is the powder in this little tin?

It is bug powder, I say; but find that this is not understood. He frowns and looks suspicious. He is obviously suspecting me of being a drug-smuggler. It is not powder for the teeth, he says accusingly, nor for the face; for what, then? Vivid pantomime by me! I scratch myself realistically, I catch the interloper. I sprinkle the woodwork. Ah, all is understood! He throws back his head and roars with laughter, repeating a Turkish word. It is for them, the powder! He repeats the joke to a colleague. They pass on, enjoying it very much. The Wagon Lit conductor now appears to coach us. They will come with our passports to demand how much money we have, ‘effectif, vous comprenez?’ I love the word effectif—it is so exactly descriptive of actual cash in hand. ‘You will have,’ the conductor proceeds, ‘exactly so much effectif!’ He names the sum. Max objects that we have more than that. ‘It does not matter. To say so will cause you embarrassments. You will say you have the letter of credit or the travellers’ cheques and of effectif so much.’ He adds in explanation: ‘They do not mind, you comprehend, what you have, but the answer must be en règle. You will say—so much.’

Presently the gentleman in charge of the financial questions comes along. He writes down our answer before we actually say it. All is en règle. And now we are arriving at Stamboul, winding in and out through strange wooden slatted houses, with glimpses of heavy stone bastions and glimpses of sea at our right.

A maddening city, Stamboul—since when you are in it you can never see it! Only when you have left the European side and are crossing the Bosphorus to the Asian coast do you really see Stamboul. Very beautiful it is this morning—a clear, shining pale morning, with no mist, and the mosques with their minarets standing up against the sky.

‘La Sainte Sophie, it is very fine,’ says a French gentleman.

Everybody agrees, with the regrettable exception of myself. I, alas, have never admired Sainte Sophie! An unfortunate lapse of taste; but there it is. It has always seemed definitely to me the wrong size. Ashamed of my perverted ideas, I keep silent.

Now into the waiting train at Haidar Pacha, and, when at last the train starts, breakfast—a breakfast for which one is by now quite ravenous! Then a lovely day’s journey along the winding coast of the Sea of Marmora, with islands dotted about looking dim and lovely. I think for the hundredth time that I should like to own one of those islands. Strange, the desire for an island of one’s own! Most people suffer from it sooner or later. It symbolizes in one’s mind liberty, solitude, freedom from all cares. Yet actually, I suppose, it would mean not liberty but imprisonment. One’s housekeeping would probably depend entirely on the mainland. One would be continually writing long lists of grocery orders for the stores, arranging for meat and bread, doing all one’s housework, since few domestics would care to live on an island far from friends or cinemas, without even a bus communication with their fellow-kind. A South Sea island, I always imagined, would be different! There one would sit, idly eating the best kinds of fruit, dispensing with plates, knives, forks, washing up, and the problem of grease on the sink! Actually the only South Sea islanders I ever saw having a meal were eating platefuls of hot beef stew rolling in grease, all set on a very dirty table-cloth.

No; an island is, and should be, a dream island! On that island there is no sweeping, dusting, bedmaking, laundry, washing up, grease, food problems, lists of groceries, lamp-trimming, potato-peeling, dustbins. On the dream island there is white sand and blue sea—and a fairy house, perhaps, built between sunrise and sunset; the apple tree, the singing and the gold…

At this point in my reflections, Max asks me what I am thinking about. I say, simply: ‘Paradise!’

Max says: ‘Ah, wait till you see the Jaghjagha!’

I ask if it is very beautiful; and Max says he has no idea, but it is a remarkably interesting part of the world and nobody really knows anything about it!

The train winds its way up a gorge, and we leave the sea behind us.

The next morning we reach the Cilician Gates, and look out over one of the most beautiful views I know. It is like standing on the rim of the world and looking down on the promised land, and one feels much as Moses must have felt. For here, too, there is no entering in… The soft, hazy dark blue loveliness is a land one will never reach; the actual towns and villages when one gets there will be only the ordinary everyday world—not this enchanted beauty that beckons you down…

The train whistles. We climb back into our compartment.

On to Alep. And from Alep to Beyrout, where our architect is to meet us and where things are to get under way, for our preliminary survey of the Habur and Jaghjagha region, which will lead to the selection of a mound suitable for excavation.

For this, like Mrs Beeton, is the start of the whole business. First catch your hare, says that estimable lady.

So, in our case, first find your mound. That is what we are about to do.

CHAPTER 2 (#ulink_e5b06a6b-7855-5cd3-91d5-39b80522299e)

A Surveying Trip (#ulink_e5b06a6b-7855-5cd3-91d5-39b80522299e)

Beyrout! Blue sea, a curving bay, a long coastline of hazy blue mountains. Such is the view from the terrace of the Hotel. From my bedroom, which looks inland, I see a garden of scarlet poinsettias. The room is high, distempered white, slightly prison-like in aspect. A modern wash-basin complete with taps and waste-pipe strikes a dashing modern note.

(#litres_trial_promo) Above the basin and connected to the taps is a large square tank with removable lid. Inside, it is full of stale-smelling water, connected to the cold tap only!

The arrival of plumbing in the East is full of pitfalls. How often does the cold tap produce hot water, and the hot tap cold! And how well do I remember a bath in a newly equipped ‘Western’ bathroom where an intimidating hot-water system produced scalding water in terrific quantities, no cold water was obtainable, the hot-water tap would not turn off, and the bolt of the door had stuck!

As I contemplate the poinsettias enthusiastically and the washing facilities distastefully, there is a knock at the door. A short, squat Armenian appears, smiling ingratiatingly. He opens his mouth, points a finger down his throat, and utters encouragingly ‘Manger!’

By this simple expedient he makes it clear to the meanest intelligence that luncheon is served in the dining-room.

There I find Max awaiting me, and our new architect, Mac (Robin Macartney), whom as yet I hardly know. In a few days’ time we are to set off on a three months’ camping expedition to examine the country for likely sites. With us, as guide, philosopher, and friend, is to go Hamoudi, for many years foreman at Ur, an old friend of my husband’s, and who is to come with us between seasons in these autumn months.

Mac rises and greets me politely, and we sit down to a very good if slightly greasy meal. I make a few would-be amiable remarks to Mac, who blocks them effectively by replying: ‘Oh, yes?’ ‘Really?’ ‘Indeed?’

I find myself somewhat damped. An uneasy conviction sweeps over me that our young architect is going to prove one of those people who from time to time succeed in rendering me completely imbecile with shyness. I have, thank goodness, long left behind me the days when I was shy of everyone. I have attained, with middle age, a fair amount of poise and savoir faire. Every now and then I congratulate myself that all that silly business is over and done with! ‘I’ve got over it,’ I say to myself happily. And as surely as I think so, some unexpected individual reduces me once more to nervous idiocy.

Useless to tell myself that young Mac is probably extremely shy himself and that it is his own shyness which produces his defensive armour, the fact remains that, before his coldly superior manner, his gently raised eyebrows, his air of polite attention to words that I realize cannot possibly be worth listening to, I wilt visibly, and find myself talking what I fully realize is sheer nonsense. Towards the end of the meal Mac administers a reproof.

‘Surely,’ he says gently in reply to a desperate statement of mine about the French Horn, ‘that is not so?’

He is, of course, perfectly right. It is not so.

After lunch, Max asks me what I think of Mac. I reply guardedly that he doesn’t seem to talk much. That, says Max, is an excellent thing. I have no idea, he says, what it is like to be stuck in the desert with someone who never stops talking! ‘I chose him because he seemed a silent sort of fellow.’

I admit there is something in that. Max goes on to say that he is probably shy, but will soon open up. ‘He’s probably terrified of you,’ he adds kindly.

I consider this heartening thought, but don’t feel convinced by it.

I try, however, to give myself a little mental treatment.

First of all, I say to myself, you are old enough to be Mac’s mother. You are also an authoress—a well-known authoress. Why, one of your characters has even been the clue in a Times crossword. (High-water mark of fame!) And what is more, you are the wife of the Leader of the Expedition! Come now, if anyone is to snub anyone, it is you who will snub the young man, not the young man who will snub you.

Later, we decide to go out to tea, and I go along to Mac’s room to ask him to come with us. I determine to be natural and friendly.

The room is unbelievably neat, and Mac is sitting on a folded plaid rug writing in his diary. He looks up in polite inquiry.

‘Won’t you come out with us and have tea?’

Mac rises.

‘Thank you!’

‘Afterwards, I expect you’d like to explore the town,’ I suggest. ‘It’s fun poking round a new place.’

Mac raises his eyebrows gently and says coldly: ‘Is it?’

Somewhat deflated, I lead the way to the hall where Max is waiting for us. Mac consumes a large tea in happy silence. Max is eating tea in the present, but his mind is roughly about 4000 B.C.

He comes out of his reverie with a sudden start as the last cake is eaten, and suggests that we go and see how our lorry is getting on.